Atmospheric, mysterious and dramatic, this quintessential example of “musical impressionism” is captivating to play and to hear. In less than 6 minutes of music, Debussy tells a remarkable story and creates a vivid aural, and visual, portrayal of the mythical cathedral of Ys, on the coast of Brittany, Northwest France in the Bay of Douarnenez France, which was said to rise from the waves, complete with bells chiming, priests chanting, and its organ playing, before sinking back into the water. Only distant bells are faintly audible as a memory – was it real or just a mirage? It’s one of my most favourite piano works by Debussy and a piece which I have been playing since I was a child (despite not having sufficiently large hands for some of the big chords and stretches!). Debussy enjoyed playing this piece himself too and even left a recording on a piano roll.

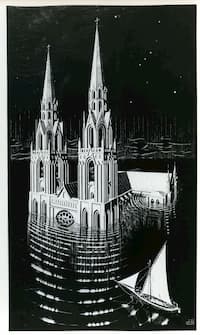

La Cathedrale engloutie – Escher

(Brigham Young University Museum of Art)

In this piece, composed in 1910 and included in Book 1 of the Preludes for piano, Debussy demonstrates his mastery of not only the piano miniature form in creating such a potent narrative in just a few pages of music, but also his deep appreciation of the instrument’s sonic palette. His music is often compared to the paintings of Claude Monet, in which ‘impressions’ of a scene or landscape are rendered through a limited palette and short brush strokes applied over a pale-coloured ground or ‘base’, which create remarkable luminosity, texture and colour blends. This has led to a misconception in the interpretation and performance of Debussy’s music in which some performers “blur” the sounds, often with over-use of the sustaining pedal.

In fact, Debussy disliked the term “impressionist”, and any temptation to employ “impressionistic” pedalling is misguided. Monet and other Impressionist painters did not blend their colours but in fact separated them – it is this separation which creates the remarkable effects of light, when viewing their paintings at a distance. Similarly, when playing and, more specifically, pedalling Debussy’s piano music, “separation” or definition of individual timbres is required; if anything, his music demands an almost Mozartian clarity.

Le Mont-Saint-Michel

Debussy did not give this prelude, nor the others in the two books, a title on the opening page. Instead each one was assigned a number, with the title placed at the end of the piece, allowing pianists to form their own individual, intuitive impressions of the music before the composer reveals his intent.

Like Monet’s pale ground on which he built his paintings, Debussy’s employs a “ground” in the opening section of the music in the form of whole-bar chords in open fifths. Over this, another chordal figure, also in open fourths and fifths, which recalls the harmonies and timbres of gamelan music, which Debussy encountered at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889, and also the simple harmonies of early Medieval liturgical music. The opening direction Profondément calme sets the scene, while the secondary direction Dans une brume doucement sonore (“in a soft mist of sound”) should not be taken as an excuse to depress the pedal fully. The arc of the phrases is perhaps suggestive of the cathedral’s gradual emergence from the sea, and indeed the overall structure of the entire piece suggests an arch form.

A key change into B Major signals a shift in the narrative. Here the cathedral begins to emerge more distinctly from the mists and waves: this is portrayed through an arpeggiated figure in the bass which evokes the rolling movement of the sea. Chords continue in the right hand: this is the sound of the organ growing louder as the cathedral emerges. By bar 28, the organ is heard in all its grandeur, with dense fortissimo chords in treble and bass. This is the climax of the music and here we can imagine the cathedral fully visible, its organ playing in glorious full volume. The weight and power of the organ is further emphasised by the tolling of a single bell, deep in the bass. At bar 41 the cathedral begins to retreat and by bar 47, the organ is heard distantly as the water subsumes the building, but bursting forth again, momentarily, at bars 59-62.

In the closing section of the piece another rolling figure in the low bass represents the sea while the organ is heard faintly, also in a lower register. One senses its magnificence, even if obscured by the water. Finally, in the final measures, the cathedral’s bells are heard distantly in haunting pianissimo.

In the video below, created by the piano department of the London College of Music, a process known as “hyper production” was used to create a “layered” performance of the piece. The score was divided into separate elements, such as “bells” or “monks’, which then informed the treatment of each element in the recording process to create a more intense and colourful sound when played back through a 3D Audio speaker array (like surround sound). It’s certainly an interesting approach – though the result may not to be everyone’s taste – and I think it is instructive as it clearly highlights and differentiates the individual motifs of the music.

The entire piece is remarkably graphic, with a clarity and layering of contrasting voices and timbres which calls for extremely precise yet highly expressive playing. Managing the climactic episode is an exercise in control to portray the full grandeur of the organ, and the monumentalism of the cathedral itself as it rises from the waves and swell of the ocean.

Here is François-Joël Thiollier’s performance:

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I agree. It is the most extraordinary composition because it is so orchestral in nature and conjures up an impression of something deeply grounded and even growing in the earth.