Beethoven

Of all the piano sonatas to choose, from the wit of Haydn, the elegance and chiaroscuro of Mozart, the poignancy of Schubert, Chopin’s restless romanticism, Rachmaninoff’s Russian heart, the biting narrative of Prokofiev’s War Sonatas, and many, many more which flood this popular genre – I choose Beethoven’s penultimate piano sonata, No. 31 in A-flat, Opus 110.

And why? Maybe I have a ‘thing’ for penultimate sonatas, those last-but-one utterances; Schubert’s expansive and warm-hearted D959 is another favourite. Or perhaps it is because, in my opinion, this is simply one of the most beautiful, extraordinary creations ever written for the piano.

Much has been written about Beethoven’s final sonatas. Although they are not the last works he wrote for the instrument, they are his last in the piano sonata genre, and as such are often regarded as his final words thereon. (The Op. 126 Bagatelles which follow seem like a distillation of the final three sonatas in exquisite microcosm.)

Composed in 1821, the Opus 110 shares the same humanity and transcendent, other-worldly atmosphere of its neighbours, and its first movement is a close cousin of Op. 109: both display a warm lyricism and tenderness. It is also remarkably compact – some 19 minutes in length (half the length of Schubert’s penultimate piano sonata), it is a distillation of ideas of compelling meaning and profound expression by a composer who has all but rejected the rules of classical sonata form. Indeed, in the hands of certain performers, it opens out like a fantasy, improvisatory and constantly intriguing and challenging. Here too, Beethoven harks back to Bach and the Baroque, especially in the final two movements, and forward to Schumann’s Gesänge der Frühe (Songs of Dawn) in the Sonata’s emotional scope.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-Flat Major, Op. 110 (Jonathan Biss, piano)

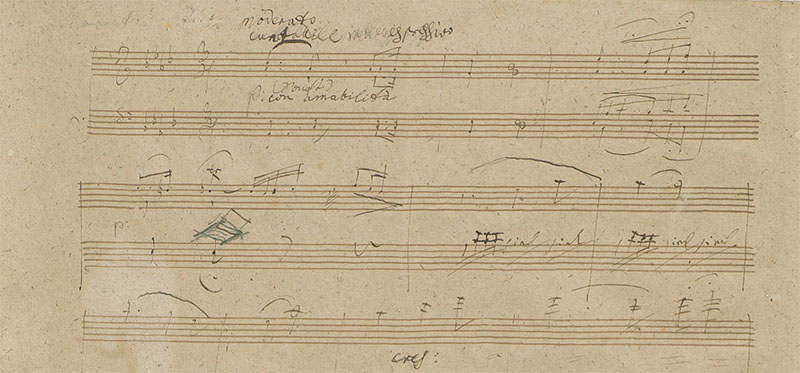

Manuscript of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 110 – opening of the first movement © IMSLP

The first movement begins with a prayer-like theme, marked con amabilita (amiably) and sanft (German for gently or softly), the first subject introduced in a classical way before dissolving into a tracery of delicate demisemiquaver arpeggios, which span the almost full compass of the piano, and from here on, the main theme is heard in fragments, except for a formal iteration of it in C minor from bar 40. The demisemiquavers accompany the recapitulation of the opening melody, enveloping it in a soft but rich filigree texture of shifting harmonies.

The gentle atmosphere of the opening movement is swiftly banished by a vigorous scherzo, which takes its themes from two rambunctious German folksongs Unsa Kätz häd Katz’ln g’habt (Our cat has had kittens) and Ich bin lüderlich, du bist lüderlich (I’m a dissolute slob, and so are you). A coda of chords, at first imposing and gradually decreasing in intensity and tempo until the movement draws to a close with a broken chord in the bass in quiet but not entire settled F major.

The final two movements of the work are as one, yet they mine a rich seam of emotions, from the doleful Arioso, whose hushed, sobbing chords are presaged by a solemn, operatic recitative, to the life-affirming fugue, which rings out as if announcing a rebirth. It’s a remarkably cathartic movement, the glorious triumphalism of the fugue contrasted by the mournful, emotional urgency of the Arioso. Beethoven manages his narrative superbly: just as we think the existential threat portrayed in the Arioso has been defeated by the fugue, so the recitative returns, marked Ermattet, klagend (“exhausted, weeping”), and this time it is even more tragic than before, now barely breathing. The gradual return to life comes at bar 132 with the introduction of a G major chord (the tonic of the fugue which follows) and the reiteration of that chord followed by a broken chord which leads into the final fugue. It begins quietly, gradually increasing in intensity and volume, Beethoven’s explicit directions scattered through the score to advise the performer as the music gathers in confidence. In the final bars, the filigree arpeggios of the opening movement reappear, this time marked forte, bringing the sonata to its joyful and overwhelming close.

“In a last euphoric effort, its conclusion reaches out beyond homophonic emancipation, throwing off the chains of music itself.” – Alfred Brendel

“Opus 110 is a journey into the infinite” – Jonathan Biss

Yes! If I were restricted to playing only one piece of music, this would be it. When asked what his thoughts were of Germany, Menachem Pressler quite simply responded, “Opus 110”.

Op. 109, 110, and 111 are the cat’s pajamas!

I so enjoyed reading your article about Beethoven’s remarkable Piano Sonata in A flat, Op.110. One of my early piano teachers worked with the great artist Solomon Cutner and his recording of that Sonata is incomparable. Just savour his exquisite voicing, the subtlety of Beethoven’s phrases and delicacy of the ‘piano’ figurations… Bliss!