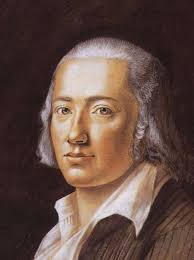

Friedrich Hölderlin

Today, as we celebrate the 250th birthday of Friedrich Hölderlin (1770–1843), we consider him among the greatest of German lyric poets. During his lifetime, however, Hölderlin gained little recognition—he was a colleague of Hegel and Schelling—and he was almost totally forgotten for nearly 100 years. Essentially, he was rediscovered in Germany only during the early years of the 20th century, and instantly admired for his uniquely expressive style.

Hölderlin is credited with reconciling the Christian faith with the religious spirit and beliefs of ancient Greece, as he “succeeded in naturalizing the forms of classical Greek verse in the German language.” For a good many musicians and artists he became a prophet of spiritual renewal, a visionary with unique access to the truth of existence. Curiously, Hölderlin’s musical reception in the 19th century seems completely independent of the literary reception. The first Hölderlin songs date from 1826, and Joseph Joachim planned a symphony on “Hyperions Schicksalslied.” That plan did not reach fruition, but it was Johannes Brahms who finalized his own work on that text in 1871, known as the Schicksalslied, Op. 54 for choir and orchestra.

Hölderlin is credited with reconciling the Christian faith with the religious spirit and beliefs of ancient Greece, as he “succeeded in naturalizing the forms of classical Greek verse in the German language.” For a good many musicians and artists he became a prophet of spiritual renewal, a visionary with unique access to the truth of existence. Curiously, Hölderlin’s musical reception in the 19th century seems completely independent of the literary reception. The first Hölderlin songs date from 1826, and Joseph Joachim planned a symphony on “Hyperions Schicksalslied.” That plan did not reach fruition, but it was Johannes Brahms who finalized his own work on that text in 1871, known as the Schicksalslied, Op. 54 for choir and orchestra.

You wander above in the light

on soft ground, blessed genies!

Blazing, divine breezes

brush by you as lightly

as the fingers of the player

on her holy strings.

Fateless, like sleeping

infants, the divine beings breathe,

chastely protected

in modest buds,

blooming eternally

their spirits,

and their blissful eyes

gazing in mute,

eternal clarity.

Yet there is granted us

no place to rest;

we vanish, we fall –

the suffering humans –

blind from one

hour to another,

like water thrown from cliff

to cliff,

for years into the unknown depths.

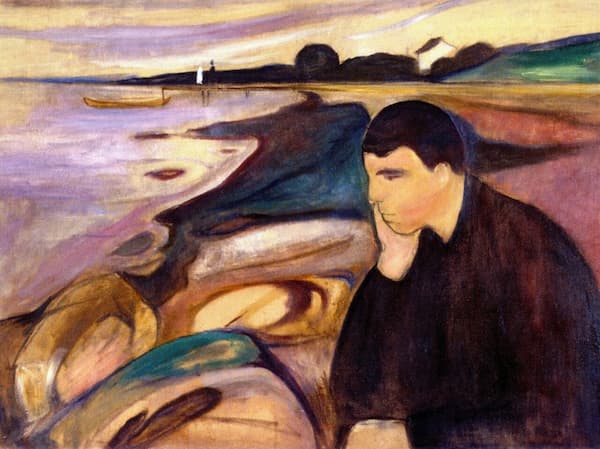

Hegel, Schelling, Hölderlin

In his setting, Brahms “creates a harmonic synthesis where Hölderlin has constructed a disharmonic, unreleased duality.” While the world of the gods contains calm, lightness, timelessness and clarity in the two first strophes, the opposite characteristics of unrest, pain, brevity of life and uncertainty conjures up the fate of humanity in the third strophe. “Whereas Hölderlin let man stand unreleased in his misery, Brahms brings comfort and release with his musical repetition of the image of the divine.” Hölderlin, who spent the last four decades of his life in dysfunctional insanity, was rediscovered by Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche regarded Hölderlin as the “founder of the idea of Greece as the model for an authentic Germany.” And it was via the early Nietzsche that Richard Strauss found his way to Hölderlin. He composed his “Drei Hymnen” during his period in Vienna, and the movements regale in the power of humanity and freedom, and the power of love to overcome all obstacles. Inspired by Hölderlin’s colorful language, Strauss crafted a work that many scholars consider a forerunner to his “Four Last Songs.”

Richard Strauss: 3 Hymnen von Friedrich Hölderlin, Op. 71, TrV 240 (Karita Mattila, soprano; Johannes Kosters, baritone; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

In 1912, Max Reger composed his expressive reading of Hölderlin’s late ode “An die Hoffnung,” Op. 124.

O hope, benignly active one,

Who do not scorn the house of the sorrowing

And glad to serve,

to rule between mortals,

Where are you? Little yet have I lived; but cold

My evening breathes. And silent already, like

The shades, I walk here while songlessly

Slumbers my shuddering heart.

……

The poet is using images and mythological epithets to personify an abstract idea, while Reger reads it as a monodrama about the yearning for a loved person with the epithet “hope.” Hölderlin’s protagonist seeks hope, but is unable to find it as the search for hope is almost forgotten after the first stanza. Reger leaves no doubt about what is being searched for, as the text “Oh Hope” is repeated throughout the song. His vocal line is filled with expressive passion with both harmony and dynamics supporting a seemingly premature climax of finding. Reger’s musical reading turns Hölderlin’s complex and ambiguous poem “into a straightforward love fantasy.

The poet is using images and mythological epithets to personify an abstract idea, while Reger reads it as a monodrama about the yearning for a loved person with the epithet “hope.” Hölderlin’s protagonist seeks hope, but is unable to find it as the search for hope is almost forgotten after the first stanza. Reger leaves no doubt about what is being searched for, as the text “Oh Hope” is repeated throughout the song. His vocal line is filled with expressive passion with both harmony and dynamics supporting a seemingly premature climax of finding. Reger’s musical reading turns Hölderlin’s complex and ambiguous poem “into a straightforward love fantasy.

Max Reger: An die Hoffnung, Op. 124 (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra; Gerd Albrecht, cond.)

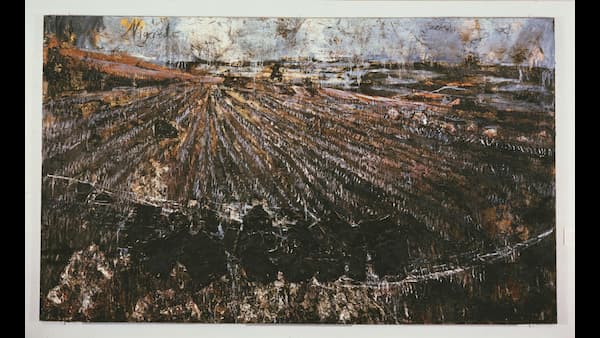

Britten’s Six Hölderlin Fragments date from 1958. The title is somewhat misleading, as it simply described the brevity of the selected poems; five of the six texts are merely one or two strophes long. It has been suggested that Britten was interested in the concept of the antique torso in the shape of remnants of Ancient Greek thought and culture in Hölderling’s poetry. “The classification ‘fragments’ points to an understanding of Antiquity, like Auguste Rodin had in the visual arts, in which one admires the torso-like and realizes this view in one’s own work. Britten sees such remnants of antique thought and poetry in Hölderlin’s poems, and it was his aim to form the entire song cycle from the understanding of the antique singer.” As such, Britten turns to Hölderlin not as a critic of language, but as a mediator of genuine ruins of the Ancient Greek culture. More recently, Hölderlin’s poetry has frequently serves as an invitation to experimentation. Composers like Bruno Maderna and Henri Pousseur don’t see Hölderling as a visionary who has found the world, “but rather as an experimenting critic of language who is incessantly searching for the word.”

Britten’s Six Hölderlin Fragments date from 1958. The title is somewhat misleading, as it simply described the brevity of the selected poems; five of the six texts are merely one or two strophes long. It has been suggested that Britten was interested in the concept of the antique torso in the shape of remnants of Ancient Greek thought and culture in Hölderling’s poetry. “The classification ‘fragments’ points to an understanding of Antiquity, like Auguste Rodin had in the visual arts, in which one admires the torso-like and realizes this view in one’s own work. Britten sees such remnants of antique thought and poetry in Hölderlin’s poems, and it was his aim to form the entire song cycle from the understanding of the antique singer.” As such, Britten turns to Hölderlin not as a critic of language, but as a mediator of genuine ruins of the Ancient Greek culture. More recently, Hölderlin’s poetry has frequently serves as an invitation to experimentation. Composers like Bruno Maderna and Henri Pousseur don’t see Hölderling as a visionary who has found the world, “but rather as an experimenting critic of language who is incessantly searching for the word.”

Benjamin Britten: 6 Hölderlin Fragmente, Op. 61 (Ian Bostridge, tenor; Antonio Pappano, piano)