A common nature drama in the equatorial region of Africa, possibly in what is now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, unleashed a global pandemic that is still one of the world’s most serious public health challenges. A troop of Chimpanzees, as they do on occasion, hunted and ate two smaller species of monkeys, each carrying slightly different strains of a virus identified as Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV).

A common nature drama in the equatorial region of Africa, possibly in what is now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, unleashed a global pandemic that is still one of the world’s most serious public health challenges. A troop of Chimpanzees, as they do on occasion, hunted and ate two smaller species of monkeys, each carrying slightly different strains of a virus identified as Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV).

Once these two viruses had found a common host in the Chimpanzee, they joined together to form a third virus labeled SIVcpz. This particular virus was now capable of being passed on to other chimps. When the infected chimps were killed and eaten, the virus transferred to humans and adapted itself within its new human host to become HIV-1. There are a number of additional HIV strains, but this seems to be the current thinking on the origin of HIV. The first verified case of HIV in humans was identified in 1959, and by the early 1980s rare diseases and opportunistic infections sprung up in the United States, with the disease named AIDS in 1982. Between the time that AIDS was identified and 2018, the disease caused an estimated 32 million deaths worldwide. However, modern advances in treatment means that people living with HIV in countries with good access to healthcare very rarely develop AIDS once they are receiving treatment. There still is no cure or vaccine, but antiretroviral treatment can slow the course of the disease and may lead to a near-normal life expectancy.

Once these two viruses had found a common host in the Chimpanzee, they joined together to form a third virus labeled SIVcpz. This particular virus was now capable of being passed on to other chimps. When the infected chimps were killed and eaten, the virus transferred to humans and adapted itself within its new human host to become HIV-1. There are a number of additional HIV strains, but this seems to be the current thinking on the origin of HIV. The first verified case of HIV in humans was identified in 1959, and by the early 1980s rare diseases and opportunistic infections sprung up in the United States, with the disease named AIDS in 1982. Between the time that AIDS was identified and 2018, the disease caused an estimated 32 million deaths worldwide. However, modern advances in treatment means that people living with HIV in countries with good access to healthcare very rarely develop AIDS once they are receiving treatment. There still is no cure or vaccine, but antiretroviral treatment can slow the course of the disease and may lead to a near-normal life expectancy.

Barry Schrader: Monkey King “The Birth of Monkey” (Barry Schrader, electronics)

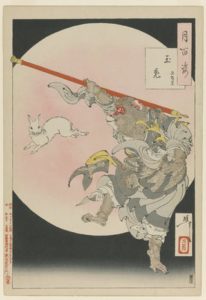

Jade Rabbit: Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, from the series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

The term “monkey” in scientific use also includes apes like chimpanzees, gibbons, and gorillas. Squabbles regarding this common classification none withstanding, these magnificent animals have long inspired religious reference and worship, and they have numerously appeared in popular culture. Worshipped by the ancient people of Peru and Mexico, the prominent deity in Hinduism is a human-like monkey god who is believed to bestow courage, strength and longevity. The three wise monkeys revered in Japanese folklore embody the principle of “see no evil, hear no evil, and speak no evil,” while in Buddhism the monkey is an early incarnation of Buddha. And they don’t get more powerful than the legendary Monkey King, a figure originating in the Song dynasty. Born from stone, the Monkey King acquires supernatural powers, and after his rebelling against heaven he is imprisoned under the mountain by the Buddha. In a different time and place altogether, Henry Purcell relied on an adaptation of Shakespeare’s comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream for his setting of The Fairy-Queen. Composed as he approached the end of his all too brief career, The Fairy-Queen contains some of Purcell’s finest theatre music, and that includes a number of “monkey” references and dances in the concluding act.

Henry Purcell: The Fairy Queen (Scholars Baroque Ensemble)

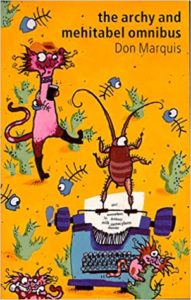

“Archy” and “Mehitabel”

The American humorist, playwright, journalist and author Donald Marquis (1878-1937) might not be a household name in Europe, but his characters “Archy” and “Mehitabel” became famous fictitious characters in his days. The character of “Archy” is a fictional cockroach, who had been a poet in a previous life. Supposedly, he leaves poems on Marquis’ typewriter by jumping on the keys during the night. Since Archy is unable to operate the shift key, all his poems are typed in lower-case letters without punctuation. “Mehitabel” is an alley cat, and an occasional companion of Archy, frequently the subject of one or the other satirical verse. “Archy at the zoo” tells of the character’s adventure at the zoo where he sees all manner of creatures. Geoffrey Bush composed a musical setting of this encounter in 1994, which includes a humorous take on Archie’s meeting with a man and his closest living relative.

Geoffrey Bush: archy at the zoo, “Man and Monkey” (Susanna Fairbairn, soprano; Matthew Schellhorn, piano)

Erik Satie, year 1909

In 1913, Erik Satie wrote the text for a play in one act entitled Le piège de Méduse (The Ruse of Medusa). Baron Medusa, an elderly and confused gentleman of private means, has retired to his estate. The insufferable servant Polycarpe, who enters his master’s bedroom every hour to take his temperature, and to give him a new one, attends to the Baron. Medusa has a young daughter, Frisette, who is courted by the young Astolfo. In nine scenes the play develops as a funny succession of misunderstandings to see if Astolfo can escape from the trap Medusa has set for him to see if he is worthy to become his son-in-law. In the end, all come together in a communal hug. The mechanical monkey Jonah plays an important supporting part. Jonah dances the small dances that constitute the complete music of the play. An extension of Medusa’s psyche, the monkey begins to dance whenever the Baron is lost in thoughts. At the premiere, Satie placed pieces of paper between the piano strings in order to obtain a mechanical effect. Now that is what I call monkey business.

Erik Satie: Le piège de Méduse “7 Monkey Dances” (Olof Hojer, piano)