Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840) almost single-handedly established a new brand of performing musician, the touring virtuoso. In a brilliant strategy of self-promotion, he even circulated the rumor that he had sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his uncanny technical abilities. Contemporary eyewitnesses report that during performance “his eyes would roll into the back of his head while playing, revealing the whites. He played so intensely that women would faint and men would break out weeping.”

Fazil Say

Urban legend suggests that he had an obsession with gambling, and that he apparently established a gaming house in Paris in 1838, aptly named “Casino Paganini.” Whether there was any truth to this or not mattered little, as the contemporary press loved a good addiction story! Paganini did develop innovative and unique special effects for the instrument, and his exceptional skills and extreme personal magnetism greatly contributed to the history of the instrument. But what is more, his performances drew the attention of other composers to the significance of virtuosity as an element in art. This was certainly true of the 19th century, but in fact, Paganini’s influence is timeless and has reemerged with a vengeance.

Fazil Say: Paganini Variations

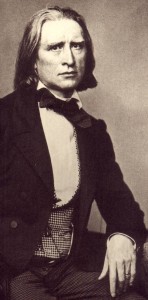

Franz Liszt

When Paganini reached Paris in 1831, he had already acquired a reputation that simultaneously elicited wonder and repulsion. Louis Spohr wrote, “In his composition and his style there is a strange mixture of consummate genius, childishness and lack of taste that alternately charms and repels.” His ten concerts at the new Paris opera house inspired press scandals and slander campaigns, but Paganini certainly knew how to exploit publicity. In April 1832, Paganini returned to Paris to play a benefit concert for the victims of a cholera epidemic that was raging through the city. And this time, a certain Franz Liszt was in the audience. For Liszt, the performance provided the “blinding flash of insight,” that for all the hype and publicity, the Paris Virtuoso School had failed to produce a comparable phenomenon among pianists. Liszt writes, “For a whole fortnight my mind and my fingers have been working like two lost souls…I practice four to five hours of exercises (thirds, sixths, octaves, tremolos, repetition of notes, cadenzas, etc). Ah! Provided I don’t go mad you will find in me an artist! Yes, an artist…such as is required today.” With Paganini in mind, Liszt created a new kind of repertoire for the piano, which transferred some of the more spectacular Paganini feats to the keyboard. The immediate result was the Clochette Fantasy of 1832, a gigantic reworking of the “La campanella” melody Paganini had used in his B-minor Violin Concerto.

Franz Liszt: Grande fantaisie di bravura sur La clochette de Paganini, Op. 2

Sergei Rachmaninoff

When Sergei Rachmaninoff departed from Russia in 1917 he was at the height of his fame as a composer, conductor and pianist. However, since his income from his prewar Russian music was not subject to international copyright, he resigned himself to the harsh life of a traveling virtuoso. Aged forty-five with his creative powers seemingly on the decline, Rachmaninoff was desperately in need of a chartbuster! So he took an old warhorse from the classical repertory, the last of the 24 Caprices for solo violin by Niccolò Paganini and fashioned a miniature piano concerto in 1934. Consisting of 24 variations on the Paganini theme, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini emphasizes a free and rhapsodic unfolding of the theme. In addition, it incorporates the old funeral chant for the Catholic Mass of the Dead providing a sense of stability and seriousness to the kaleidoscopic variations on the Paganini theme. After Rachmaninoff had put the finishing touches on his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, he rather nonchalantly remarked, “This piece is for my agent.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

Joseph Horovitz

Joseph Horovitz was born in Vienna, but immigrated to England in 1938. He studied modern languages at Oxford before attending the Royal College of Music in London. As a conductor of ballet and opera he extensively toured Europe and the United States, and was appointed professor of composition at the Royal College of Music in 1961. He composed 16 ballets and concertos for violin, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, euphonium, tuba and percussion, as well as a popular and often performed jazz concerto for harpsichord or piano. He is primarily remembered for his delightful and witty works in the popular vein, such as Captain Noah and his Floating Zoo and the Jubilee Toy Symphony. An outstandingly versatile composer, Horovitz showed great skill in writing for wind instruments and his Variations on a theme of Paganini are no exception. Just goes to show that the popularity and magnetism of the old violin wizard continue to inspire artists to and fro; more to come!