Liszt : Prélude and Fugue on the Name of B.A.C.H

Schumann : Six Fugues B-A-C-H, op. 60

During the Classical period of the 18th century, organ music was seldom written, since most composers started to write for the newly invented piano forte. We know though that the young Mozart performed on existing organs to great acclaim; early in his life he worked on church music compositions which show great interest in polyphonic structures, a practice he would take up again towards the end of his life playing organs in Dresden, Leipzig and Prague (Mozart’s works from this period include the Adagio in C-Flat KV 546 and the Leipzig Gigue in G-Sharp KV 574). The few classical organs built at that time replicated the classical architecture of the period with symmetry, balance and fewer decorations. In his classical period, the young Beethoven had been taught organ playing by teachers such as the Court musician Van den Eeden, who were still steeped in the traditional Baroque tradition. From them he became familiar with J.S. Bach’s musical concepts, and in particular with the Wohltemperierte Klavier.

During the Romantic period, organs became more of a symphonic instrument with the invention of the ‘Schwellkasten’ (an augmenting sound chamber), which could create a gradual crescendo. It is of interest to note that in the beginning of the 19th century, the composers of organ music created their works in an era that had little connection to the traditional concepts of the organ itself. With the composition for organ by Robert Schumann in his Six Etudes and his Six Fugues B-A-C-H, op. 60, we are reminded that in 1837 Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy had published his Three Préludes and Fugues op. 37, which Schumann greatly appreciated. Schumann considered Mendelssohn a lifelong friend. In 1844 Griepenkerl had published, for the first time, J.S. Bach’s complete organ repertoire — again, we have to remember that Mendelssohn was the first composer to bring Bach’s works to the public’s attention. Between 1850-1863 appear the great organ compositions by Franz Liszt, ‘Prélude and Fugue on the Name of B.A.C.H, ‘Fantasie and Fugue’ and ‘Evocation of the Sistine Chapel’.

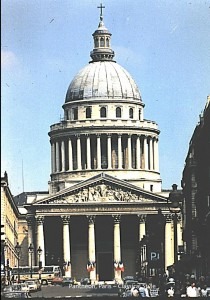

New technologies (electricity just to name one) and the work of master organ builders such as Frédéric Ladegast, Friedrich Walker and Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (e.g. Cavaillé-Coll’s famous organ in the church of St. Clôtilde, Paris, where César Franck played from 1859 until his death) – made the creation of larger organs possible, with more stops, more variation and more blending of sound and timbre. Typical of the Romantic movement in the arts, elements from ‘nature’, such as bird calls, were included. Greater wind power (multiple bellows) was required for these organs, producing an amplified, grander sound. These Romantic instruments, such as the ones built by Cavaillé-Coll in France, inspired composers, such as César Franck and Charles-Marie Widor, to create organ symphonies that would exploit the full possibilities of these symphonic organs. German composers Max Reger and Siegfried Karg-Elert created similar symphonic organ compositions making use of Romantic organs built in Germany.

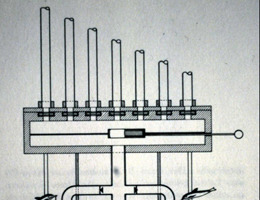

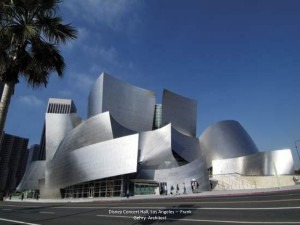

Also at this time, the organ moved out of churches into concert halls, and with the development of pneumatic and electro-pneumatic key action in the late 19th century, consoles could now be separated from the main organ. This greatly expanded new possibilities for organ design, often replicating the architectural design of the concert hall itself. Organs in concert halls were then used as part of an orchestra, as attested by compositions such as Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3 and Francis Poulenc’s, Concerto for Organs, Strings and Tympani. Many works by Gustav Holst, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Anton Bruckner, and Ralph Vaughan Williams make prominent use of organs in orchestral compositions.

With Oliver Messiaen’s organ works we move clearly into the 20th and even 21st centuries — his post-tonal music re-defining many of the ‘traditional’ notions of organ registration and technique.

The recently built organ (Glatter-Gőtz Company, Austria) in the Frank Gehry- designed Disney Music Center in Los Angeles, raises again the interesting relationship between architecture and organ. The organ is the main focus of the concert hall, with curved organ pipes reaching into the audience space at different angles, horizontally as well as vertically. Their design mirrors the building itself, where the focus is no longer a unified, centered view, but the multiple, varied perspective of modern life itself.