In his 1990 work …as others see us…, Scottish composer James MacMillan chose paintings in the National Portrait Gallery to depict in music. He started with a line from the Scottish poet Robert Burns, who wished for the gift ‘to see ourselves as others see us’ and looked at portraits, which are one aspect of how others see us and created his own sound pictures of these figures.

MacMillan opens his work in the 15th century with a portrait of King Henry VIII (1491–1547).

Unknown Artist: King Henry VIII, early 17th century (London: National Portrait Gallery)

MacMillan sees the king as rough, macho, and a bully and puts that into the music. It opens with a Scottish tune parodying a Tudor dance but with parallel harmonic layering that distorts the foreground. Later in the work, the king’s famous Greensleeves, which, the composer says, ‘over the next few centuries, was performed at public executions in England and in Europe – an apt use of a tune whose composer callously sent wives, friends and countless subjects to their deaths’. An incessant beating of a small drum, the tabor, underlies the whole movement.

James MacMillan: … as others see us … – No. 1. Henry VIII (1491-1547) (Linus Roth, violin; Julius Berger, cello; Lars Wouters van den Oudeweijer, clarinet; Netherlands Radio Chamber Philharmonic; James MacMillan, cond.)

The second portrait is of the court poet John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester. The portrait shows the poet giving his laurels to a monkey who is busy tearing out the pages of a book of Wilmot’s poetry. Wilmot served in the court of Charles II, who dismissed him from the court annually because of his satirical wit and licentiousness.

Unknown Artist: John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, ca 1665–1970 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

MacMillan uses two ideas in contrast: a slow, sustained line in the strings to represent the inspirational Muse, and a scurrying line in the winds and percussion for the destructive monkey. Eventually, the two lines merge – the poet becomes the monkey, and the monkey becomes the poet.

James MacMillan: … as others see us … – No. 2. John Wilmot (1647-1680) (Linus Roth, violin; Julius Berger, cello; Lars Wouters van den Oudeweijer, clarinet; Netherlands Radio Chamber Philharmonic; James MacMillan, cond.)

In this painting full of metaphors, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, is shown as a martial hero. To his side is Hercules, looking up at him, and behind, Discord is being trampled into the ground over emblems of war, including a shield with the sunburst design of Louis XIV. Above, a laurel wreath is being placed by the Victory, Fame blows her trumpet, and Justice sits in judgement with her scales and fasces. To the side, a kneeling woman in ermine robes offers him a castle. This is just a study for a planned painting to commemorate Churchill’s victory at Ramillies in 1706 when the Grand Alliance of England, Austria and the Dutch Republic, led by Churchill, defeated the Bourbon armies of Louis XIV.

Sir Godfrey Kneller: John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, ca 1706 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

Churchill’s martial power is conveyed by trumpet and percussion, Hercules by clarinet and bassoon, and Discord is trampled by cello and double bass. The gods in heaven are given to the flute, violin and viola.

James MacMillan: … as others see us … – No. 3. John Wilmot (1647-1680) (Linus Roth, violin; Julius Berger, cello; Lars Wouters van den Oudeweijer, clarinet; Netherlands Radio Chamber Philharmonic; James MacMillan, cond.)

Two poets take the next movement, Lord Byron and William Wordsworth. George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (1788-1824), is shown in an Albanian costume he bought in 1809 while on a Grand Tour. Byron was a major figure in the Romantic movement, as was Wordsworth, and supported the battle of Greece against the Ottoman Empire, dying there just before a battle at Lepanto (modern-day Nafpaktos).

Thomas Phillips: Lord Byron, 1835, based on a work from 1813 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

This painting is a detail from a larger three-quarter-length portrait Phillips painted some 22 years earlier, showing Byron against a Greek background, mountains and storms behind him and a Greek temple in the bottom right corner.

Thomas Phillips: Lord Byron, 1813 (Athens: British Embassy)

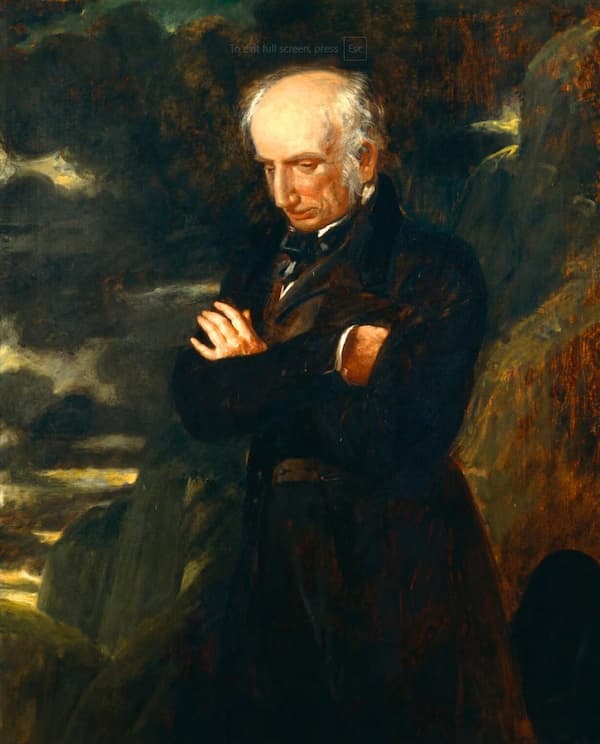

William Wordsworth (1770–1850) was a Poet Laureate of the UK. This painting is of the 72-year-old Wordsworth, commemorating a sonnet he had composed after climbing Helvellyn, a mountain in the English Lake District. It is modelled on an 1839 painting by the same artist of the Duke of Wellington surveying the Field of Waterloo.

Benjamin Robert Haydon: William Wordsworth, 1842 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

In his portraits of the two Romantic poets, Byron is given active and energetic music, as befits his fiery character. There’s also a hint of other 19th-century musical heroes in references to Wagner’s Lohengrin and Richard Strauss’ Don Juan.

Wordsworth, as befits his character and his portrait, is pensive and reflective – the composer says if an allusion to 19th-century music is to be made, it is to Beethoven’s 7th symphony.

James MacMillan: … as others see us … – No. 4. George Byron (1788-1824) and William Wordsworth (1770-1850) (Linus Roth, violin; Julius Berger, cello; Lars Wouters van den Oudeweijer, clarinet; Netherlands Radio Chamber Philharmonic; James MacMillan, cond.)

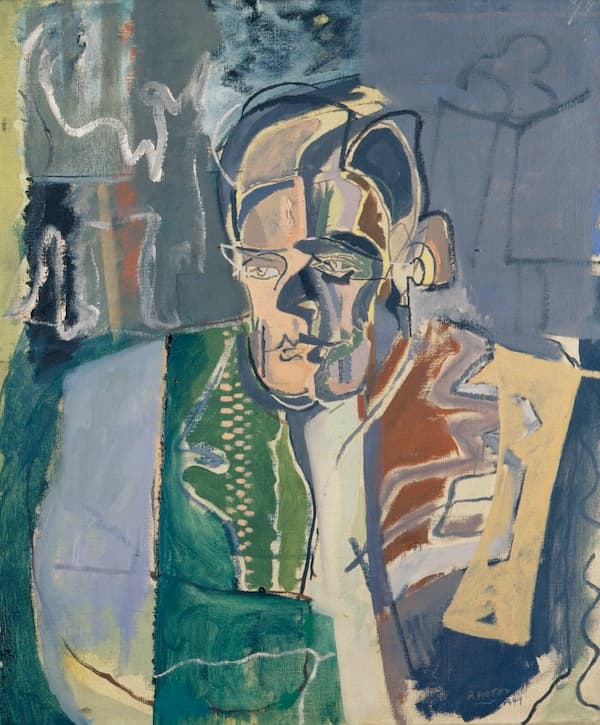

T.S. Eliot (1888–1965) is our exception to the line of British portraits because he was born in St. Louis, Missouri. However, Eliot moved to England in 1924 and became a British subject in 1927, renouncing his American citizenship.

This portrait was painted the year after Eliot was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. It is a portrait of the leading poet painted by the leading painter of the day. Both were concerned with ideas in abstraction and this work shows the borders between colours as one of the leading concerns of the painter – unlike other paintings of the time, this one is carefully delineated while remaining abstract.

Patrick Heron: T.S. Eliot, 1949 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

MacMillan’s portrait of Eliot captures two sides of this 20th-century poet: the American fascinated with England and the rituals of England (here given in ‘quasi-liturgical’ music) and the American who maintained an interest in things American (here with reference to 1920s jazz, in which Eliot held a keen interest.

James MacMillan: … as others see us … – No. 5. Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888-1965) (Linus Roth, violin; Julius Berger, cello; Lars Wouters van den Oudeweijer, clarinet; Netherlands Radio Chamber Philharmonic; James MacMillan, cond.)

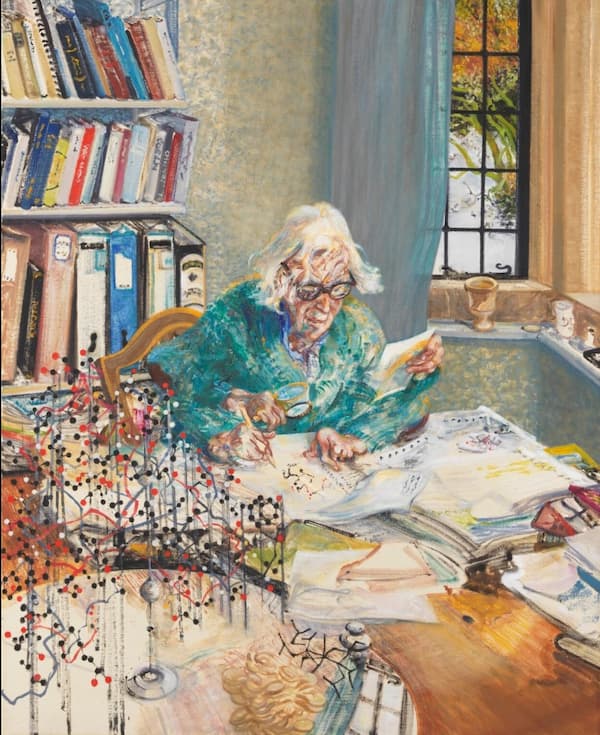

Maggi Hambling’s portrait of chemist Dorothy Hodgkin (1910–1994) at work in her study. In front of her is a structural model of insulin, and she is so busy at her work that she’s shown with 4 hands twisted with arthritis, which she contracted when she was 28.

She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her work on mapping the structure of vitamin B12; her model of insulin took 35 years of work.

Maggi Hambling: Dorothy Hodgkin, 1985 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

MacMillan makes his own musical structure out of ‘a) a melodic interaction between violin and clarinet and b) an imploding durational process on piccolo, trumpet and contrabassoon’. In his music, the two processes gradually merge to become a single element.

James MacMillan: … as others see us … – No. 6. Dorothy Mary Hodgkin (b. 1910) (Linus Roth, violin; Julius Berger, cello; Lars Wouters van den Oudeweijer, clarinet; Netherlands Radio Chamber Philharmonic; James MacMillan, cond.)

The Scottish dance tune that we first heard in King Henry VIII’s portrait carries through all the portraits, varies accordingly to ‘reflect the character of the person portrayed and the historical period’. This is the composer’s point of view – bringing in a Scottish dance tune to represent his point of view as a Scottish composer. Thus, we have the artists’ view of their subjects and the composer’s view of the same people.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter