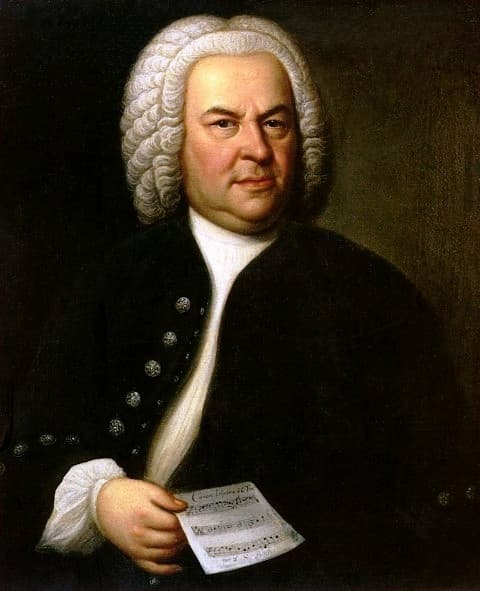

In his Goldberg Variations, Musical Offering, and the canonic variations on “Vom Himmel hoch,” Bach pursued canonic procedure to its absolute limits. The use of canon no longer merely serves to lend emphasis or cogency to the composer’s part-writing, but it now assumed a primary role of artistic design and expression. There can be no doubt that the Goldberg Variations (BWV 988) stand as one of the crowning achievements of Western classical music. This extraordinary set is grouped into ten sets of three variations, with the third variation of each set being a canon following an ascending pattern. As such, variations 3 is a canon at the unison, variation 6 is a canon at the interval of a second, and the final variation, instead of being the expected canon at the tenth is a quodlibet—combining several popular tunes in counterpoint. From this simple structural outline, we can readily tell that number symbolism—particularly the numbers three and two—plays integral structural roles throughout the compositions. Variation three is the first genuine canon of the set, and since the canon imitates the unison with parts crossing constantly, it’s terribly difficult to perform. In addition, the canonic voices appear to function almost independently of the bass line.

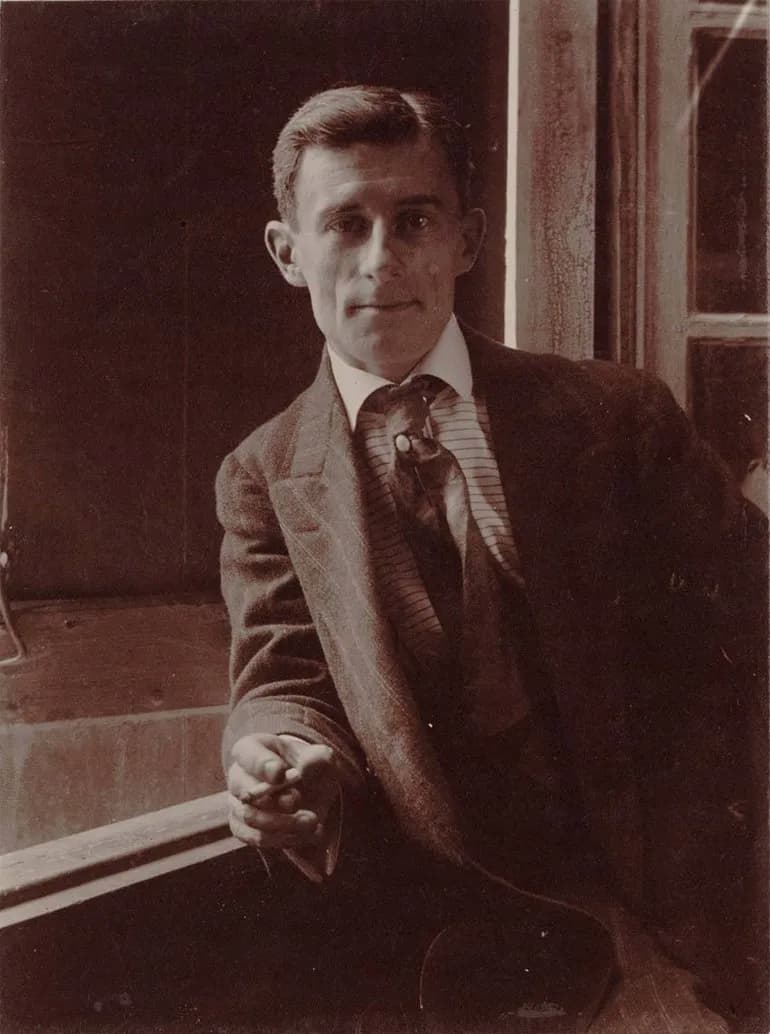

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone all’Unisono” (Glenn Gould, piano)

Johann Sebastian Bach

Variation 6 is a canon at the interval of a major second. Bach uses this variation to exploit the harmonic tensions created by this type of close canon. Despite its harmonic tensions, however, Bach infuses this canon with an almost nostalgic tenderness.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone alla Seconda” (Glenn Gould, piano)

In Variation 9 Bach sounds a canon at the interval of a third. Much less dissonant than the canon at the second, the voice crossing is somewhat delayed and harmonic dissonances increase only gradually. Bach also places more emphasis on the supporting bass line, which becomes slightly more active.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone alla Terza” (Glenn Gould, piano)

Canonic—that is exact imitation—at the interval of the fourth and fifth creates a unique set of problems with those pesky tritones and unwanted modulations never far away. In fugal practices, these dissonances are avoided by slightly adjusting the imitating voice. But then, it wouldn’t be a canon. Bach deals with this problem in Variation 12 by presenting the answer in inversion. That is, the follower enters in the second bar at the interval of a fourth, but in contrary motion to the leader.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone alla Quarta” (Glenn Gould, piano)

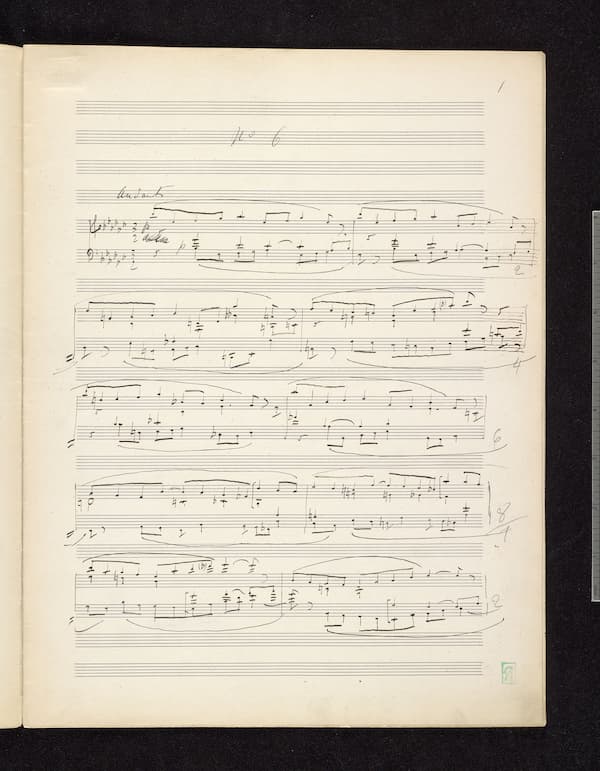

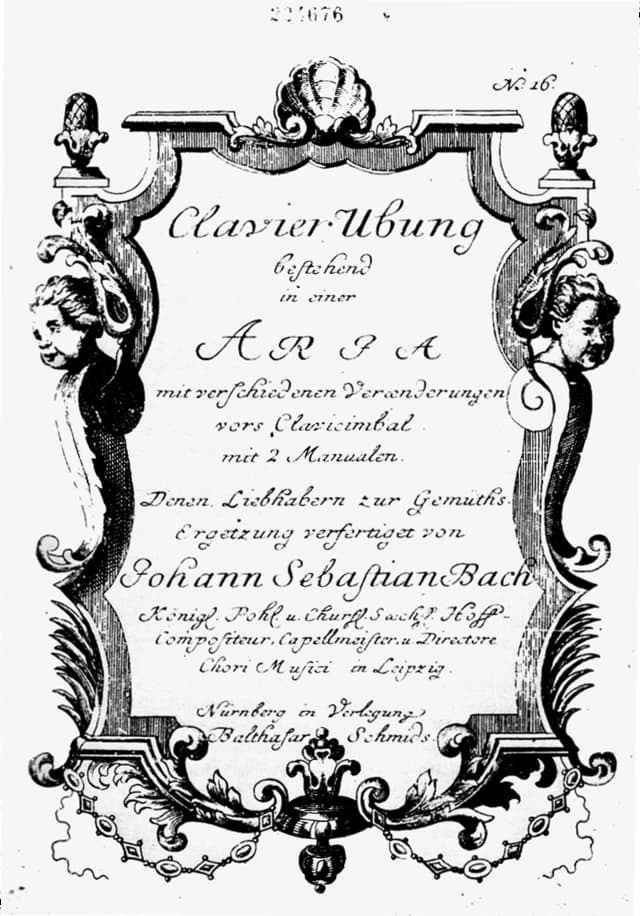

Goldberg Variations title page of the 1st edition

At the halfway point of the set, Variation 15 presents a truly radical departure from all that has come before. This canon at the interval of a fifth—with the answer once again appearing in contrary motion—is cast in the minor mood. It instantly creates a melancholic and contemplative mood, sharply contrasting with the playfulness of the previous variations. In addition, the bass line is now so well integrated into the canon that it imitates the canonic lines. This canon has been seen as the representation of the highest level of thematic integration, and Glenn Gould stated, “it’s the most severe and rigorous and beautiful canon … the most severe and beautiful that I know, the canon in inversion at the fifth. It’s a piece so moving, so anguished, and so uplifting at the same time that it would not be in any way out of place in the St. Matthew’s Passion.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone alla Quinta” (Glenn Gould, piano)

By Variation 18, the major mode has returned in a canon at the interval of the sixth. The canonic interplay features many delicious suspensions, and this canon has been called “an imperious, totally confident movement which must be among the most supremely logical piece of music ever written.” And for Glenn Gould, it represents an “extreme example of deliberate duality of motivic emphasis.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone alla Sexta” (Glenn Gould, piano)

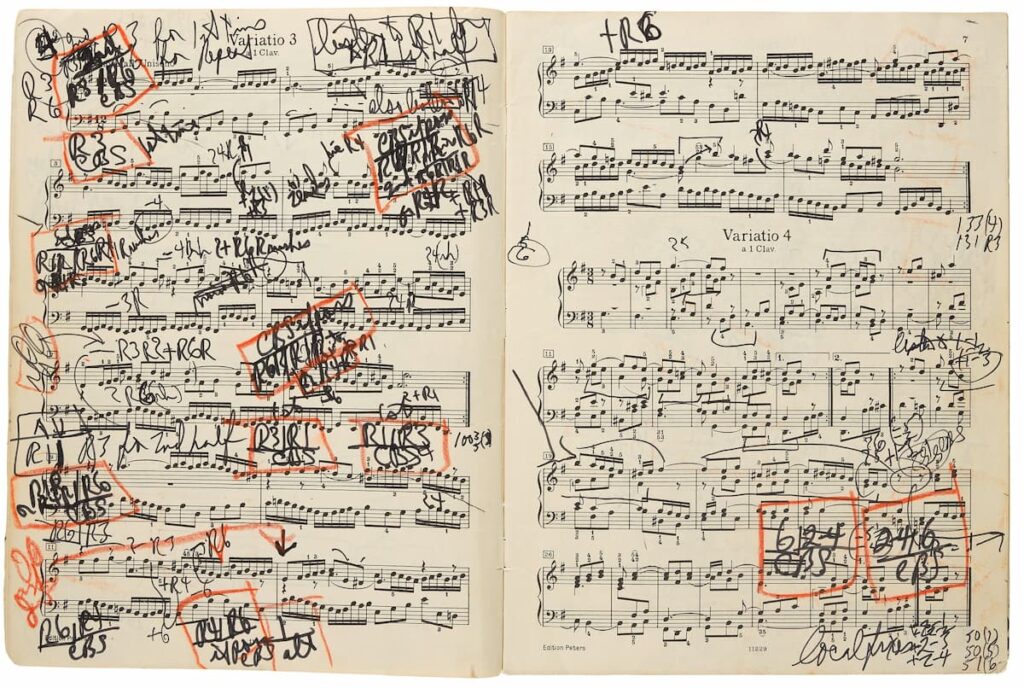

Glenn Gould markings in the Goldberg Variations

Variation 21 is the second of three minor-key variations, presenting a canon at the interval of a seventh. Almost chorale-like or in the manner of an Allemande, the tone is somber and somewhat tragic. However, while leaning on chromatic intervals, the eloquent bass line manages to be largely in the major mode.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone alla Settima” (Glenn Gould, piano)

In Variation 24, the canonic imitation has reached the octave. Initially, the canonic line is answered at the octave below, and the second canonic line is answered at the octave above. Vaguely pastoral in quality, this procedure is predictable for Bach, reversed in the second half.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone all’Ottava”

3 Canons from the Goldberg

The canon at the ninth featured in Variation 27 is specified to be played on two manuals. Since the voices do not cross, Bach wanted the two canonic lines to be heard clearly. Technical perfection and canonic inventiveness aside, in his Goldberg Variations, Bach provided for the whole range of human emotion. In fact, he might well be looking at the totality of humanity. But his point of view is neither elitist nor condescending. And it certainly does not contain embittered negativism or any conspiracy paranoia. As has been suggested, “here Bach represents every quality of humanity except imperfection.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations “Canone alla Nona” (Glenn Gould, piano)