I have recently been fascinated by the art music of Estonia, partially fuelled by the success of Arvo Pärt. But as I have explored in earlier blogs, this triumph of Estonian culture would not have been possible without the groundwork prepared by Rudolf Tobias and Eduard Tubin (1905-1982).

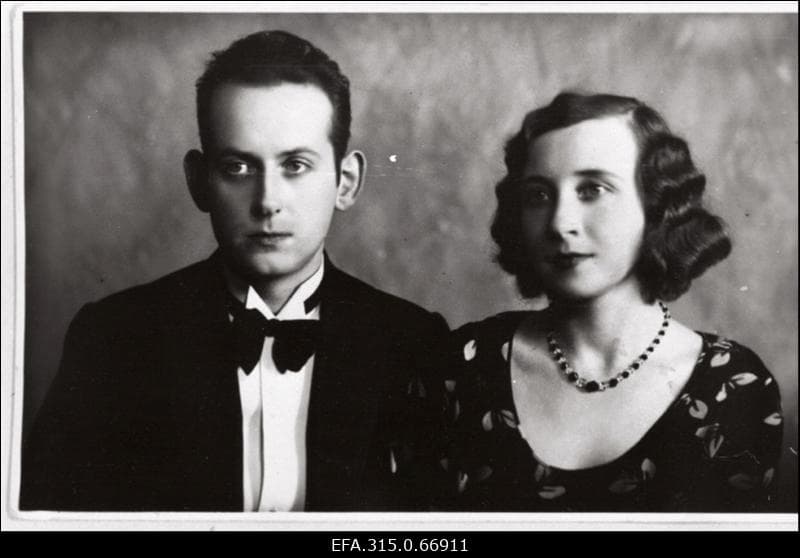

The young Eduard Tubin

Tubin was one of the most prominent figures in the history of Estonian art music, but forced by political circumstances, he fled to Sweden and worked hard to re-establish his career in a new country. His ten symphonies are at the pinnacle of Estonian orchestral music and much of the same could be said about his stage works. As such, we decided to take a look at a composer who remains largely unknown and definitely undervalued.

Eduard Tubin: Kratt “The Goblin” (Excerpts)

Early Steps

Eduard Tubin was born on 18 June 1905 far from the cosmopolitan capital of Tallinn, in a little village on Lake Peipus, the vast inland water that forms Estonia’s eastern boundary with Russia. His father was a fisherman and tailor, but an avid music lover who played trumpet in the village band. When Eduard’s musical talents had been recognised he learned the balalaika and flute and played in the school band, and later in the village band as well.

The Republic of Estonia formally declared independence on 24 February 1918. That independence lasted the better part of one day, as the country was quickly occupied by the German Empire, and following World War II, Estonia was incorporated into the Soviet Union. Tubin trained as a teacher, and he was admitted to the Tartu Higher Music School to study with the famous Estonian composer Heino Eller. He made his name as a competent and busy choral conductor and went to Vienna, Budapest, Paris, and Leningrad to further his studies.

Eduard Tubin: Sinfonietta on Estonian Motifs (Estonian National Symphony Orchestra; Arvo Volmer, cond.)

Musical Voice

Eduard Tubin and his wife

Tubin met Zoltán Kodály in Budapest, who encouraged his interest in folk music. In fact, Tubin went to the Estonian island of Hiiumaa to collect folk songs in the summer of 1938.

As a scholar writes, Tubin’s career began at a time when “nationalist-romantic and modernist currents overlapped in independent Estonia. His nationalism subsumed the work of three Estonian forebears: the drama and large-scale forms of Tobias, the subtle orchestral virtuosity of Eller, and Saar’s attempt to meld Estonian folklore with a nationalist concert style.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Tubin made his international reputation with symphonies that lacked folkloristic elements. He often uses the modality and intervallic constructions of Estonian folk music, but his first three symphonies are marked “by a rhythmically propulsive and ecstatic orchestral style that reflects Tubin’s interest in Scriabin and Eller’s brand of impressionism.”

Eduard Tubin: Symphony No. 2 “The Legendary”

Orchestral Essay

Tubin’s second symphonic essay bears the subtitle “The Legendary,” perhaps implying a specific program. The composer, similar in the way of Nielsen and Prokofiev, brings a narrative theatricality to orchestral and concert genres. Tubin immediately grasps large-scale structures, and although he displays a mastery of polyphony, his orientation is essentially linear and dramatic. In his symphonies, Tubin often employs cyclic unity, avoiding thematic areas and clear recapitulation.

“The Legendary” was performed in 1938, and some critics complained of the density of sound and disharmonies. Such assessments later gave way to “formally perfect and enormously expressive music, something of an instrumental requiem from a Europe on the brink of disaster.” And that pessimism was well founded, as Estonia was once again occupied by Soviet troops in 1940, as 100,000 soldiers rolled into the country with censorship imposed and links with other countries cut.

Eduard Tubin: Violin Concerto (Mark Lubotsky, violin; Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Catastrophe

Eduard Tubin Museum

During the early part of occupation, Tubin was appointed head of the composition class at the Tartu Conservatory, and he received commissions for new works. Tubin and his colleagues went on a cultural visit to Leningrad to study revolutionary songs and Soviet music life. Tubin was also working on his groundbreaking first ballet, Kratt, a demonic folkloric figure. Reality was no less demonic, as the first Soviet occupation was challenged by the German army, igniting a merciless civil war.

Tubin and his family had hoped that things would eventually improve, but the hardship and dangers of everyday life became unbearable. With thousands of people shot or deported to Russia, it was time to leave. They left port on 20 September 1944, but the engine failed and the boat drifted in the Baltic Sea for two days until rescued by the Swedish coast guard. For Tubin and his family, a new life had begun, but back in Estonia, musicians were subjected to show trials and scores and books mercilessly burned.

Eduard Tubin: Symphony No. 5, “Allegro energico”

A New Home/A New Style

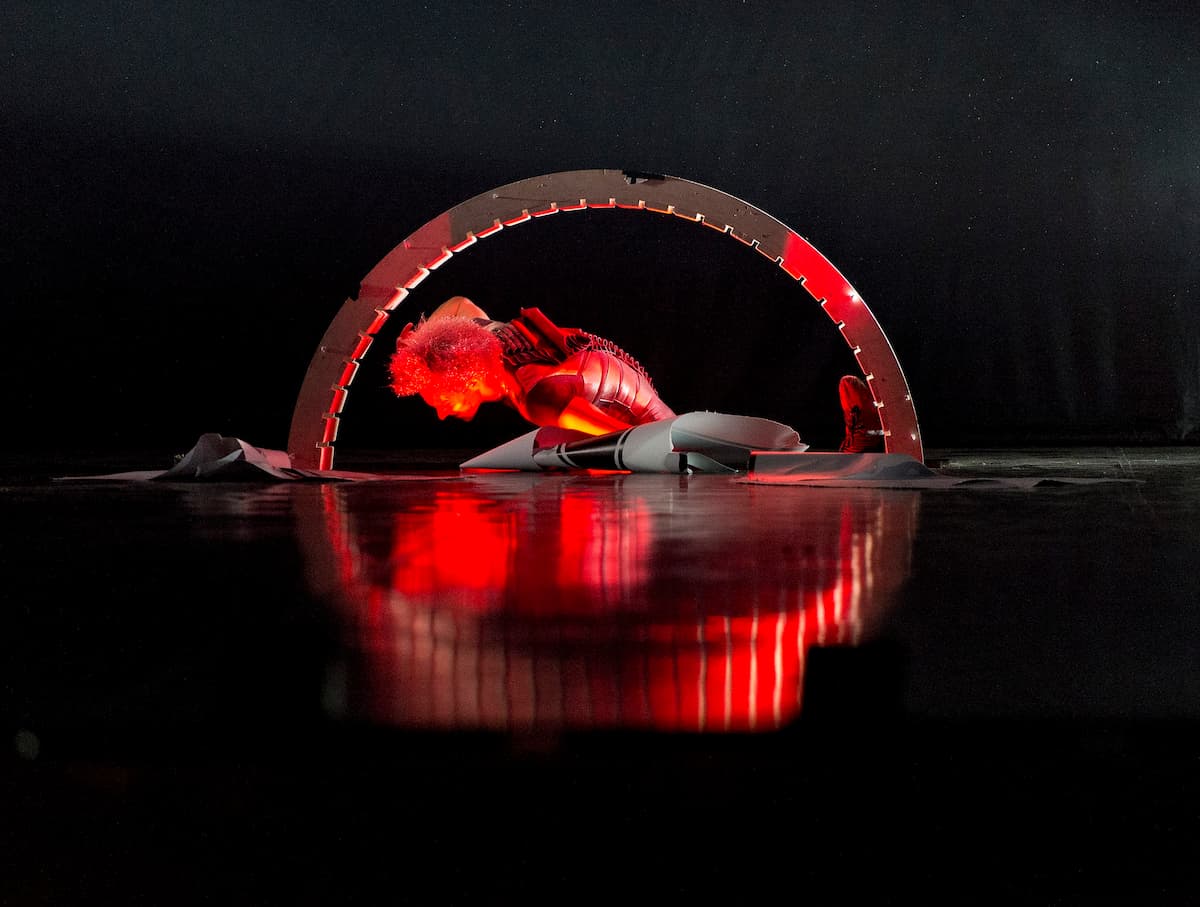

Eduard Tubin’s opera Kratt

Tubin got in touch with the music publisher Einar Kdarling and joined the Swedish Performing Rights Society, ensuring royalties for performances of his works. In 1945, he was offered a clerical position at the historic Drottningholm Theater, a job he retained for almost 30 years until his retirement in 1972. With a small but secure salary at his disposal, Tubin once again turned towards composition. The first years in Sweden were productive ones and marked by a distinct change in Tubin’s music.

According to his son Eino, “The earlier romanticism and lyricism gave way to a direct no-nonsense tonal language with strong rhythms that could sometimes even feel aggressive.” One of his early successes in this new musical style was Symphony No. 5, which was described as containing “sovereign mastery of musical form, and a musical depiction of Estonian national tragedy, though uplifting but also soothing and liberating.”

Eduard Tubin: Piano Sonata No. 2 “Northern Nights”

Northern Lights

Eduard Tubin, 1958

Scholars have suggested that a unifying characteristic of Scandinavian art-music was its “attempt to capture the play of light and darkness in the boreal climes, in instrumental textures.” Tubin concluded his ballet score Kratt with a “Dance of the Northern Lights,” and his Piano Sonata No. 2, dating from 1950, is subtitled “The Northern Lights.” Written between February and October 1950 in the suburbs of Stockholm, the work contains attributes that became hallmarks of Tubin’s mature style.

The subtitle comes from Tubin himself, and he explained that the work’s opening eight-note harmony “represents the programmatic depiction of the whirling flashes from the northern lights he witnessed in Stockholm in 1949.” The work follows a highly concentrated structure, and a tonally ambiguous harmonic design is enriched by the use of cyclically repeating theme groups. This Aurora borealis harmony is transformed throughout the work as it “becomes a vital structural element of the composition.”

Eduard Tubin: The Retreating Soldier’s Song (Roland Rydell, baritone; Janake Larson, piano; Lunds Studentsangare; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Estonia Again?

Monument of Eduard Tubin in Tartu, Estonia

Tubin’s music had been banned in Estonia from 1948 to 1956, but with increased international recognition, Soviet emissaries began to visit him every year. Tubin had by then Swedish citizenship and he resultantly agreed to visit his former homeland. That trip was not popular with expatriate colleagues, as he was seen as merely a pawn of the Estonian puppet government. Tubin later wrote that he “simply wanted to bring a breath of fresh air to his younger colleagues in Estonia and revealed himself as a free-thinking person of Western orientation.” Tubin got two opera commissions from the Estonian Theatre, but as the Soviet regime realised that Tubin would not return to Estonia for good, his music was banned again.

Tubin disliked Schoenbergian atonality and twelve-note techniques and favoured a harmonic language ranging from free chromaticism to mild polytonality. Particularly in his late works, Tubin returned to diatonic orientation, as we can hear in his String Quartet. It is based entirely on folk dances and ends with a characteristic fugue. If not for the advocacy of conductor and countryman Neeme Järvi, who emigrated from Estonia to the United States in 1980, Eduard Tubin and his music might still continue to linger in obscurity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Eduard Tubin: String Quartet (Tallinn Quartet)

Thanks (again) for this biographical sketch. I have been a fan of Tubin’s music since the first BIS lable issues, 1970s. Highly recommended