In a ranking of madcap artists and composers, Erik Satie would almost certainly take first prize. His whacky eccentricities, tied to the subconscious world of chimera and dream, are surely the essence of French decadence. As we approach his birthday on 17 May, we thought it might be fun to look at a period in his life that scholars have called his “Rosicrucian Adventure.”

Erik Satie: “Première pensée Rose + Croix” (Alessandro Simonetto, piano)

Rosicrucianism

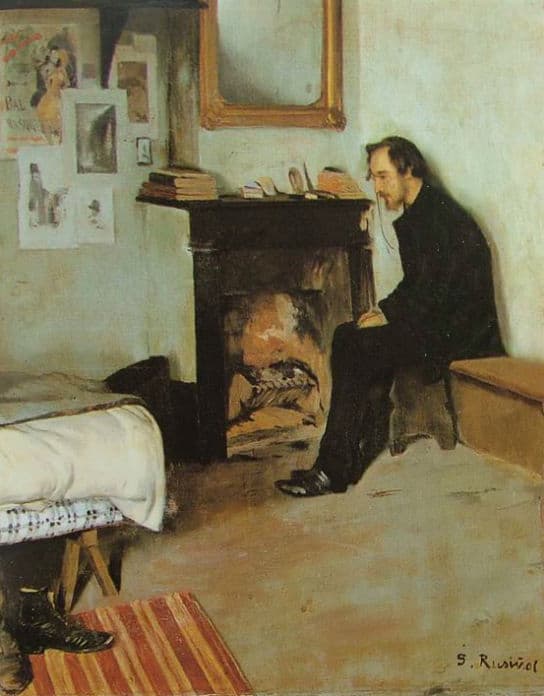

Erik Satie in his room

Erik Satie spent well over a decade of his life playing the piano and composing songs in Parisian cabarets and nightclubs. And it goes without saying that he met a number of fascinating individuals, including Joséphin Péladan. Péladan had recently established the newly formed Rosicrucian brotherhood, and he invited Satie to become the official composer of the Order.

Rosicrucianism, essentially, is a spiritual and cultural movement that originated in the early 17th century. It was a secret and esoteric organization founded on occult philosophies that proclaim to have hidden knowledge and whose symbol is the rosy cross. This brotherhood advocated a universal reformation of mankind “through a science built on esoteric truths of the ancient past.” In other words, followers of Rosicrucianism believe they are curators of an ancient, esoteric knowledge.

Erik Satie: 3 Sonneries de la Rose+Croix, “Air de l’ordre” (Aldo Ciccolini, piano)

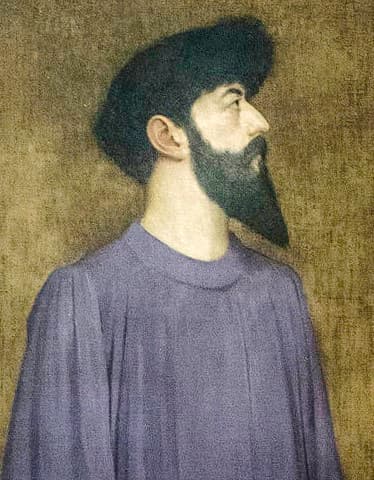

Joséphin Péladan

Joséphin Péladan

As you might well imagine, Rosicrucianism took on countless identities, and by 1890, Joséphin Péladan had broken with a group in what became known as “The War of the Two Roses.” He founded a new order of Rosicrucianism, which he called the “Order of the Catholic Rosy Cross, the Temple and the Grail.” Péladan defined it as “an intellectual brotherhood of charity, dedicated to the realization of works of mercy according to the Holy Spirit from which the members gather strength to multiply the Glory and prepare the Kingdom.”

In his many novels, written in a flamboyant and colourful style, Péladan freely mixes erotic dreams, sensualism, supernaturalism, fantasy, and strict Catholic dogma. His principal work consists of a series of twenty-one novels, all expunging his conviction that religious decay and declining faith were leading to the decadence of the Latin race.

Erik Satie: 3 Sonneries de la Rose+Croix, “Air du grand maitre” (Aldo Ciccolini, piano)

Idolatrous Harlotry

Parisfal, 1882, Act 3

“Modern man as a cosmopolitan is doomed because he has succumbed to the great harlot, Babylon,” Péladan writes. “She has seduced him from nature, from the ways of righteousness. Thus, man has passed from his holy communion with nature to the cult of artificiality, of anti-nature, in idolatrous harlotry. And life without nature is ultimately sterility, death without resurrection.”

Joséphin Péladan was also a lover of music and was completely enchanted by Richard Wagner. He recognized him as a musician of intoxicating power and as a philosopher of the new art. Péladan travelled to Bayreuth in the summer of 1888 to see Parsifal, and he regaled in its “unique synthesis of poetry, music, and drama, and above all its overriding Christian message.”

Erik Satie: 3 Sonneries de la Rose+Croix, “Air du grand prieus” (Aldo Ciccolini, piano)

Première pensée Rose + Croix

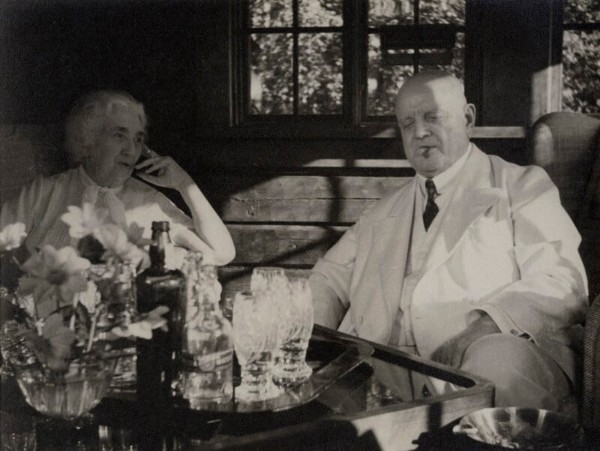

Erik Satie © Atlas Press

You can easily see why Satie would find the colourful ceremony and eccentricity of this quasi-medieval Rosicrucian rites appealing for a time. He almost certainly also found it amusing as he became part of an atmosphere filled with spiritism, artifice, and a pervasive neurotic mysticism. A contemporary report writes, “Péladan was seeing visions as the souls of the cathedrals were being discovered. Artists took refuge in the Past, in the mysticism of the Middle Ages, and allowed themselves to be lulled to rest by the religion of their childhood.”

Satie’s first musical thought on Rosicrucianism is a short eight phrase originally untitled work for piano. The title “Première pensée Rose + Croix” was supplied by the publisher in 1968, and the piece does not feature time signatures or bar lines. This absence of precise indications in Satie’s scores essentially starts with his Rose-Croix works. Scholars have noted “a predominantly tritonal relationship between chords, constant fluctuation of mode, and abrupt transposition of phrases.”

Erik Satie: Le Fils des étoiles, Act I: Prélude, “La Vocation” (Nicolas Horvath, piano)

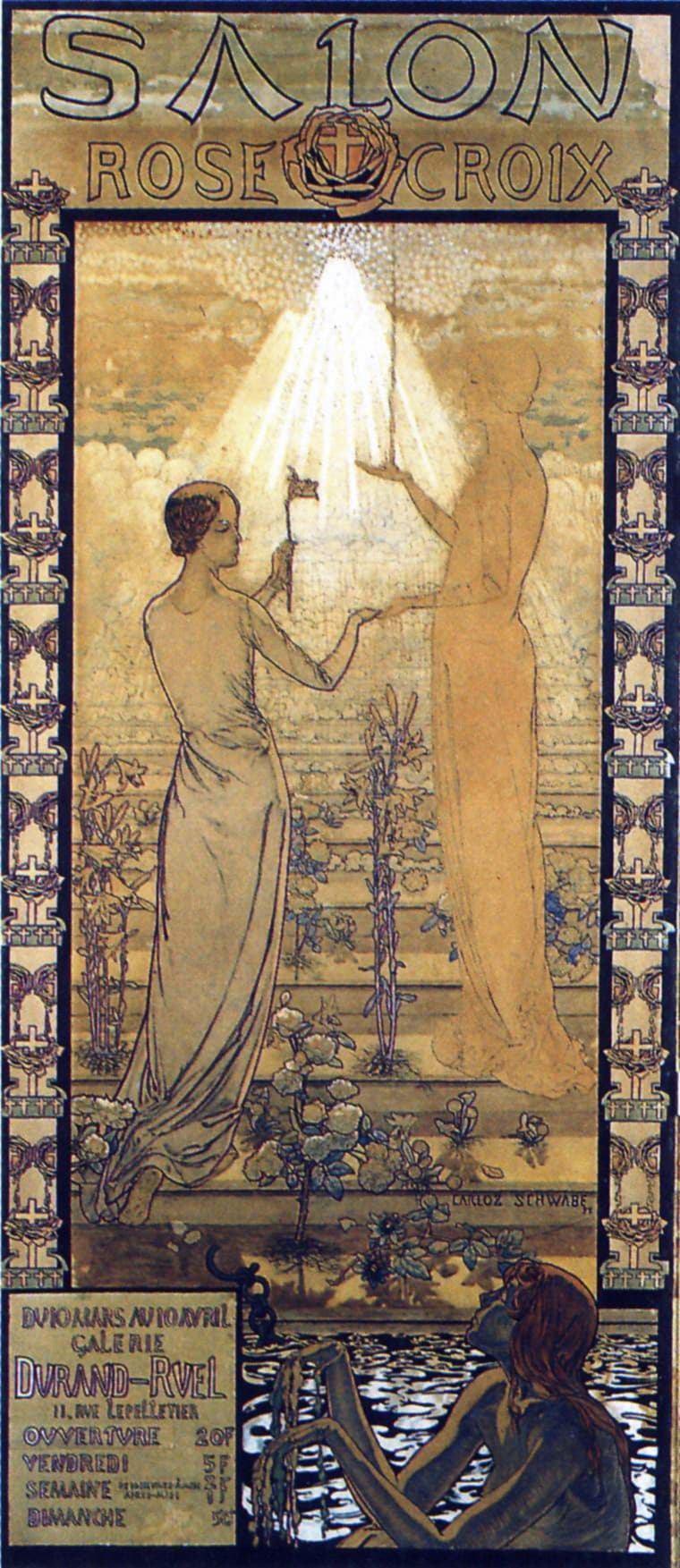

Salon de la Rose-Croix

Salon de la Rose-Croix

Péladan hosted his first Salon de la Rose-Croix between 10 March and 10 April 1892. Between 1892 and 1897, a total of 231 artists exhibited at Péladan’s Salons. Each gathering opened with a Solemn Mass of the Holy Ghost, preceded by three fanfares for harp and trumpet composed by Erik Satie, and followed by selections from Wagner’s Parsifal. The “Sonneries de la Rose+Croix” were exclusively reserved for the ceremonies of the Order and could not be played without the agreement of Péladan.

A charming anecdote relates that Satie once told Jean Cocteau about a wonderful moment when Péladan, worried about the sound of the “Sonneries for the Order,” asked if Wagner would have “written such chord.” – “Yes, yes,” he replied, his eyes smiling maliciously behind his pince-nez glasses, knowing that this was not the case. Yet there was more music emerging from this Rosicrucian Adventure, specifically incidental music to the three-act pastoral drama Le Fils des étoiles by Péladan.

Erik Satie: Le Fils des étoiles, Act II: Prélude, “L’Initiation” (Nicolas Horvath, piano)

Le Fils des étoiles

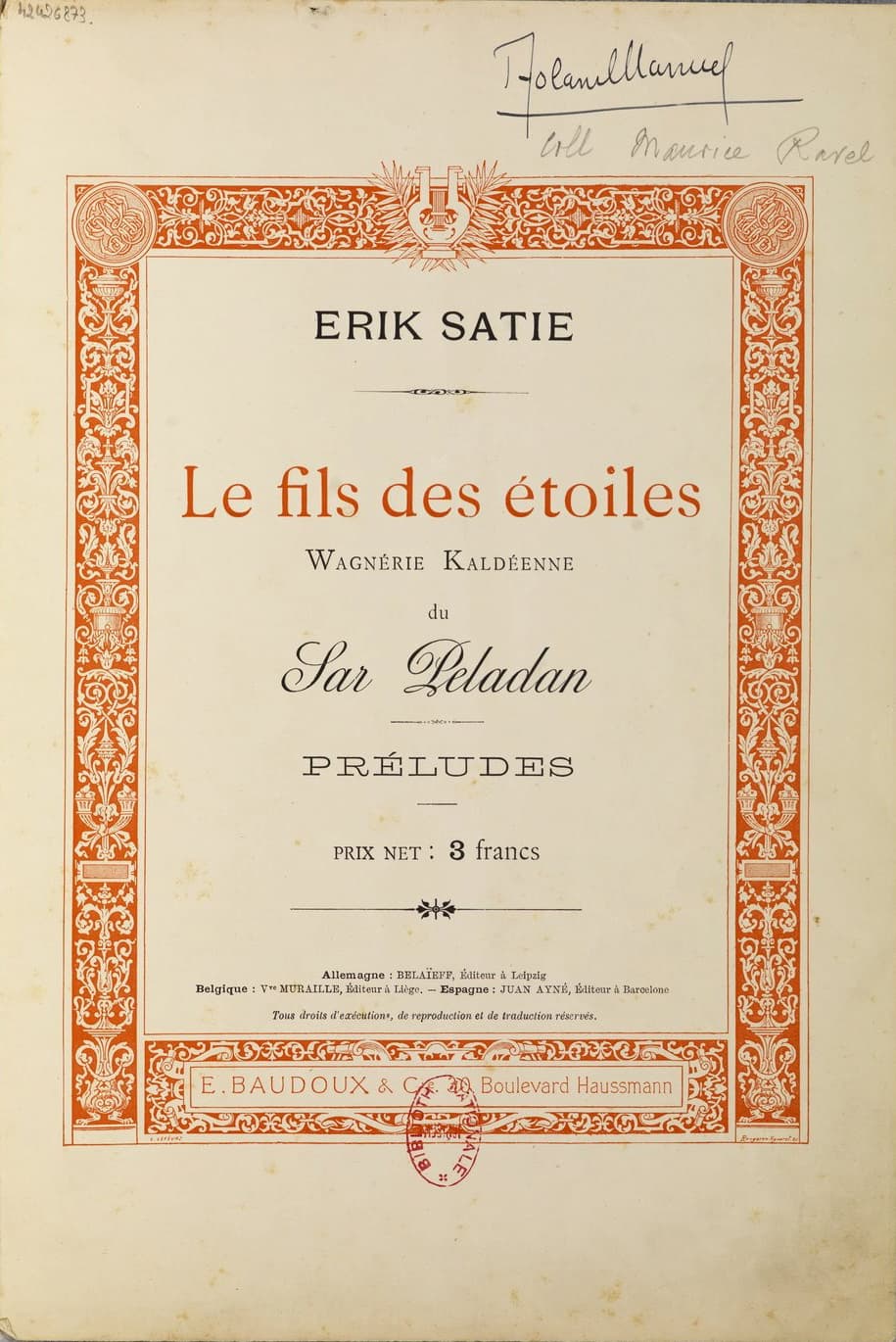

Le Fils des étoiles, 1896

Péladan authored a number of esoteric dramas, but he had trouble getting them accepted for performance. With some substantial backing, he decided to open his own Théâtre de la Rose-Croix, right next to his Rosicrucian exhibitions. He produced six dramas in that venue, two of them with incidental music by Satie. The pastoral drama Le Fils des étoiles was presented three times, but it was badly received and a financial disaster.

The story is set in Chaldea, about 3000 B.C., and features a 16-year-old androgynous shepherd boy called Oelohil. He is a true son of the stars and torn between profane and spiritual love. During his secret initiation into the Chaldean priesthood, he proves himself worthy of the high office of resisting the temptation of the flesh, and he is thus allowed to marry the young daughter of the high priest.

Erik Satie: Le Fils des étoiles, Act III: Prélude, “L’Incantation” (Nicolas Horvath, piano)

White and Motionless

Erik Satie, 1891

Although Satie composed additional music between the three acts, only the preludes were published and performed during his lifetime. The publisher even added the misleading title “Wagnerie Kaldéenne.” That edition was printed entirely in red ink and without bar lines in 1896. The music, supposedly, is scored for harps and flutes, but it is more likely that Satie played the preludes himself on piano or harmonium.

The general mood is established by a rising melody that is clearly plainsong derived and by Satie’s inscription “White and motionless” and “Pale and hieratic.” In addition, the music was announced as being of “an admirably oriental character” at the premiere. A scholar writes, as with his other Rosicrucian works, “this music reveals Satie’s obsession for vertical sonorities in strange and incongruous contexts.”

Erik Satie: Messe des Pauvres, “Kyrie” (Dresdner Kreuzchor; Michael-Christfried Winkler, organ; Ulrich Schicha, cond.)

Metropolitan Church of Art of Jesus the Conductor

Metropolitan Church of Art of Jesus the Conductor

Satie would compose in a “Rosicrucian” style until 1895, but his association with Péladan was short-lived. In March 1892, Satie started to grow increasingly unhappy with Péladan’s pageantry. And just a couple of months later, he publicly announced the break. As he writes, “the good Master Péladan has in no wise exercised authority on my Aesthetic independence… Inasmuch as I am the pupil of anyone, methinks that anyone can but be myself.”

Having initiated the break with Péladan, Satie founded his own church, the “Metropolitan Church of Art of Jesus the Conductor.” From his tiny closet room at 6 rue Cortot, which became his Abbatial Residence, Satie started issuing various edicts and excommunications. He condemned all “evildoers speculating on human corruption.”

Erik Satie: Messe des Pauvres, “Dixit Dominus” (Dresdner Kreuzchor; Michael-Christfried Winkler, organ; Ulrich Schicha, cond.)

Church Doctrine

Satie summarised the general mission of the Metropolitan Church of Art as such: “We have thus resolved, following the dictates of Our conscience and trusting in God’s mercy, to erect in the metropolis of this Frankish nation, which for so many centuries aspired above all others to the glorious title of Elder Daughter of the Church, a Temple worthy of the Saviour, conductor and redeemer of all men.”

“We shall make of it a refuge where the Catholic faith and the Arts, which are indissolubly bound to it, shall grow and prosper, sheltered from profanity, expanding in all their purity, unsullied by the workings of evil.” Satie appointed himself Parcener and Chapel Master and estimated that the number of his disciples would number in the hundreds of millions.

Erik Satie: Messe des Pauvres, “Priere des orgues” (Dresdner Kreuzchor; Michael-Christfried Winkler, organ; Ulrich Schicha, cond.)

Parody and Venom

Gauthier-Villars, or Willy

Alan Gillmor writes, “it is hard not to see Satie’s fanciful organisation, with its astronomical numbers, its elaborate hierarchical structure, and it pseudo-pious aims, as a deliberate and extravagant parody. Even his literary style can be construed as a caricature of Péladan’s bombastic prose.” Satie issued a number of publications in the name of the Metropolitan Church of Art, written in flowery and bombastic language in a sort of pseudo-antique French.

The official documents of the church, however, also served as the vehicle for scathing attacks on various critics. The pompous writer and music critic Gauthier-Villars, or Willy, as he preferred to be called, was the main target of Satie’s assaults. In Satie’s opinion, Willy “had blasphemed in passing judgments on Wagner and therefore was commanded to languish in grief, in silence, and in painful meditation.” Willy replied by dismissing Satie as a “trashy composer and inconsequential buffoon.”

Erik Satie: Messe des Pauvres, “Commune qui mundi nefas” (Dresdner Kreuzchor; Michael-Christfried Winkler, organ; Ulrich Schicha, cond.)

Satie vs Willy

Erik Satie, 1891

Satie replied, “your breath stinks of lies, your mouth spreads audacity and indecency. Your depravity has caused your own downfall; it has made your incomparable crassness clear to even the most limited of intelligence.” Mind you, this was only the beginning, as insults were traded back and forth. Satie wrote, “To think that We mistook you for a stupid barbarian, for a coward, for a rather silly and pallid reject of Literature! How wrong We were, how wrong.”

Things finally came to a head at an orchestral concert on 10 April 1904. During a performance of a Beethoven symphony Satie confronted Willy about the harsh treatment he was being dealt by the critic in the press. Willy attempted to dismiss the composer with an off-the-cuff remark, whereas Satie attacked Willy with his fists. Willy responded by swinging his walking stick, and Satie was dragged off to the police station.

Erik Satie: Messe des Pauvres, “Chant Ecclesiastique” (Dresdner Kreuzchor; Michael-Christfried Winkler, organ; Ulrich Schicha, cond.)

Messe des Pauvres

Messe des Pauvres

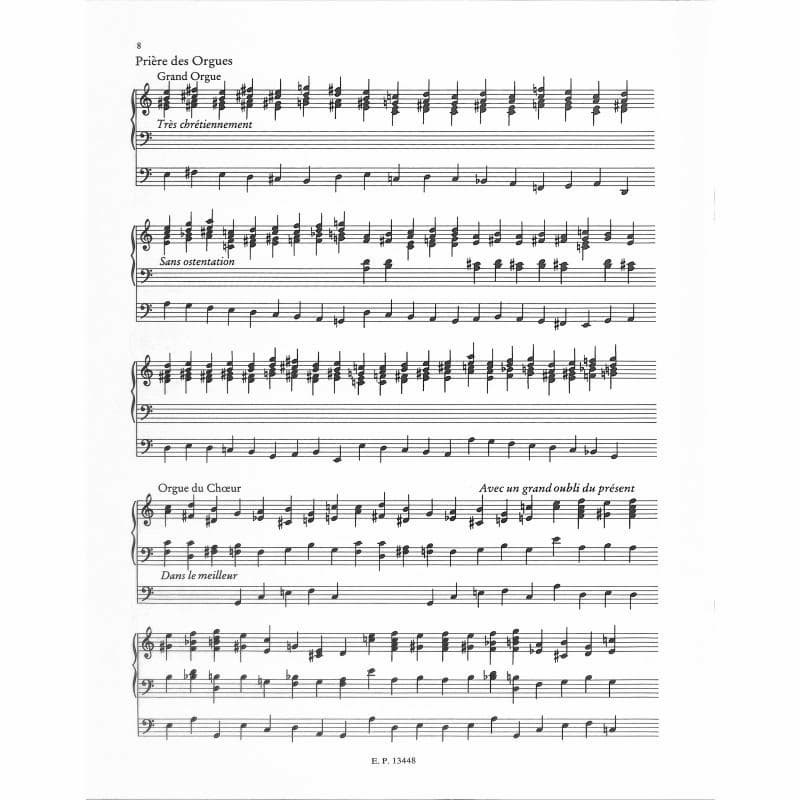

The “Mass for the Poor” is a partial musical setting of the mass for mixed choir and organ. It is Satie’s only liturgical work and the culmination of his Rosicrucian period. Fragments of the mass were published in June 1895, and it is unknown how the mass assumed its final title. The movements are scored for organ and unison high and low voices, only singing in the “Kyrie” and the “Dixit domine.”

As in his other mystic works, the harmonic vocabulary of the mass offers much parallel movement and chords built on superimposed fourths. “This mass,” he writes, “is music for the divine sacrifice, and there will be no part for the orchestra, which finds their way into most masses.” However, Satie quickly lost interest in his church, and he exchanged his robes and religious affectations for seven identical sets of corduroy suits that would come to define his “Velvet Gentleman” phase.

Erik Satie: Messe des Pauvres, “Prier pour les voyageurs….” (Dresdner Kreuzchor; Michael-Christfried Winkler, organ; Ulrich Schicha, cond.)

Hoax or Truth

There seems to be much discussion as to whether Satie’s Rosicrucian adventure was nothing more than an elaborate hoax. However, as Alan Gillmor has argued, “Satie may have sought escape for a time in his own peculiar brand of religious mysticism. Long after he had abandoned his Metropolitan Church, the composer still maintained an interest in spiritual matters and engaged in serious theological discussions.”

Nevertheless, we cannot discount the idea that the practical joke was, for a long time, the only thing that Satie took seriously. He may well have harboured genuine religious impulses, but it is hard to shake the notion that the Metropolitan Church of Art of Jesus the Conductor was simply the outward manifestation of his deep disgust “with the academy and the platitudes of bourgeois existence.” Whatever the case may be, Satie always kept his audience guessing, and the ambivalence of whether to take him seriously or laugh out loud was part of the greater overall design.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Erik Satie: Messe des Pauvres, “Prier pour le salute de mon ame” (Dresdner Kreuzchor; Michael-Christfried Winkler, organ; Ulrich Schicha, cond.)