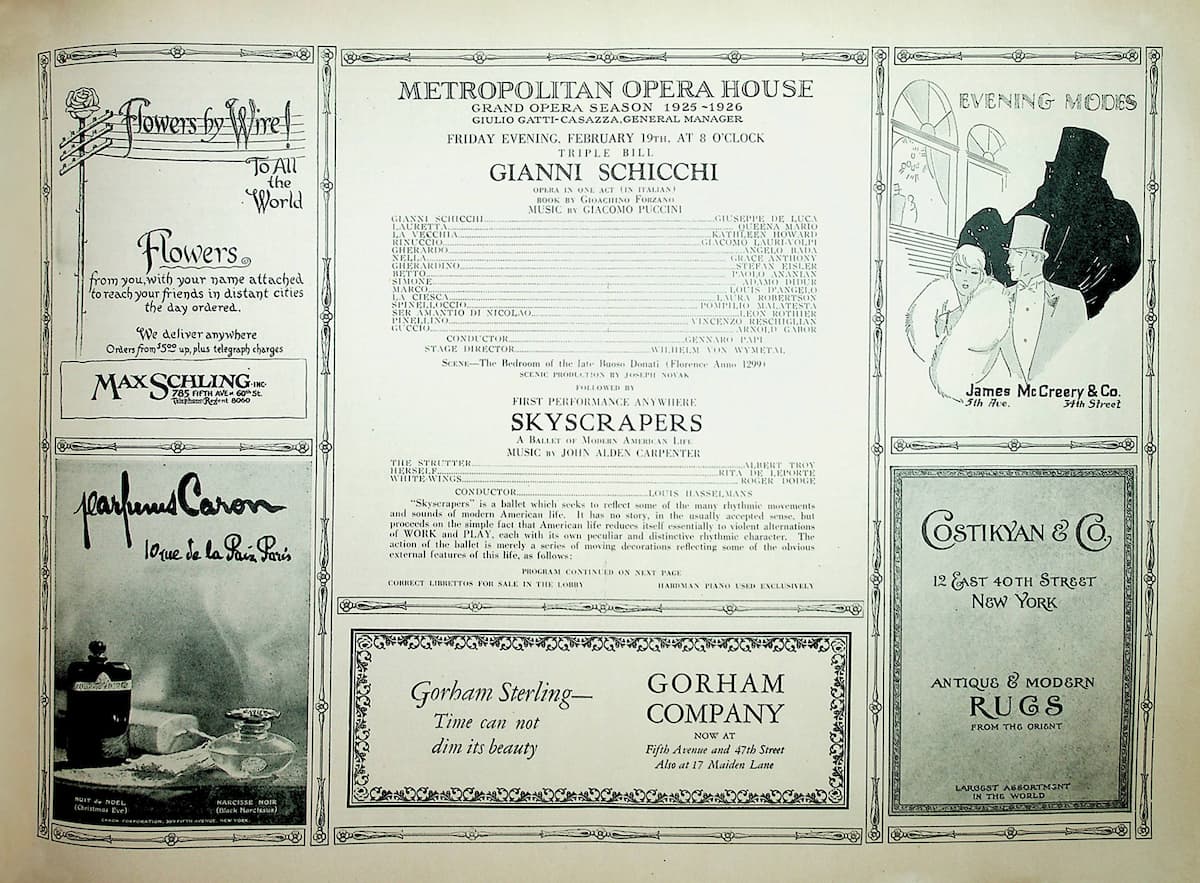

In 1926, the Metropolitan Opera staged the world premiere of the American composer John Alden Carpenter’s 1924 ballet Skyscrapers. This was in February, at the height of the season and it was a triple-bill evening: Gianni Schicchi with Giuseppe De Luca in the title role, Skyscrapers, and then Pagliacci with Vittorio Fullin in the lead role and Lawrence Tibbett as the rival lover, Silvio.

Met Opera Program for the Skyscrapers premiere

Skyscrapers, with music by John Alden Carpenter and stage designs by Robert Edmond Jones, carried the subtitle of A Ballet of Modern American Life. In his program notes for the work, Carpenter wrote:

Skyscrapers is a ballet which seeks to reflect some of the many rhythmic movements and sounds of modern American life. It has no story, in the usually accepted sense, but proceeds on the simple fact that American life reduces itself essentially to violent alternations of WORK and PLAY, each with its own peculiar and distinctive rhythmic character. The action of the ballet is merely a series of moving decorations reflecting some of the obvious external features of this life….

The ballet had three principal characters. A Broadway entertainer (Strutter), an ingenue (Rita De Leporte) depicting an ‘American girl’, and an NYC street cleaner (White Wings) wearing the regulation white uniform of the city’s municipal cleaners. Extraordinary for the time was the use of an all-black chorus and, as review after review indicates, the unprecedented naming of the choir leader, Frank H. Wilson, in the programme.

Skyscrapers principals Rita De Leporte, Albert Troy, and Roger Pryor Dodge, 1926, Met Opera (Courtesy Pryor Dodge)

Although Wilson’s appearance is frequently cited as the first appearance of blacks on the Met stage, there had been some included in the Met ballet company for the 1918 Met premiere of American composer Henry F. Gilbert’s The Dance in Place Congo. Mixed in with the white dancers performing in blackface, including Met principal dancers Giuseppe Bonfiglio and Ottokar Bartik, was a small group of black male dancers. Wilson would go on to become the first Porgy in the play Porgy and Bess in 1927.

Black singers came to the stage in Skyscrapers. The employment contract for Wilson, dated 24 December 1925 and issued on the letterhead of the Met General Manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza, requested that Wilson hire 12 singers. The 12 singers and Wilson were to be paid a total of $120 for each performance of the ballet (or a little less than $9.25 each for performance, rehearsals, and preliminary work) – the Met did six performances.

Frank H. Wilson (Courtesy South Carolina Historical Society, DuBose Heyward Collection)

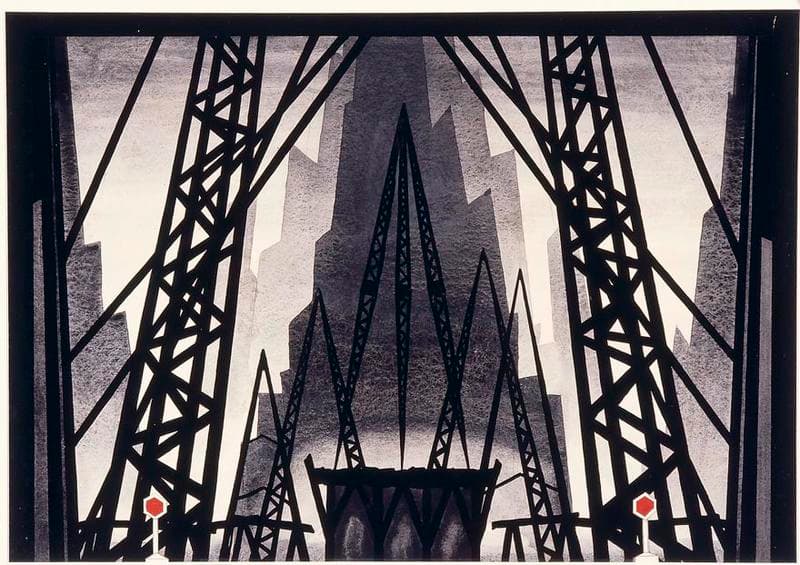

The set designs were by celebrated designer Robert Edmond Jones and evoked the world of 1920s Manhattan, starting with the curtain design.

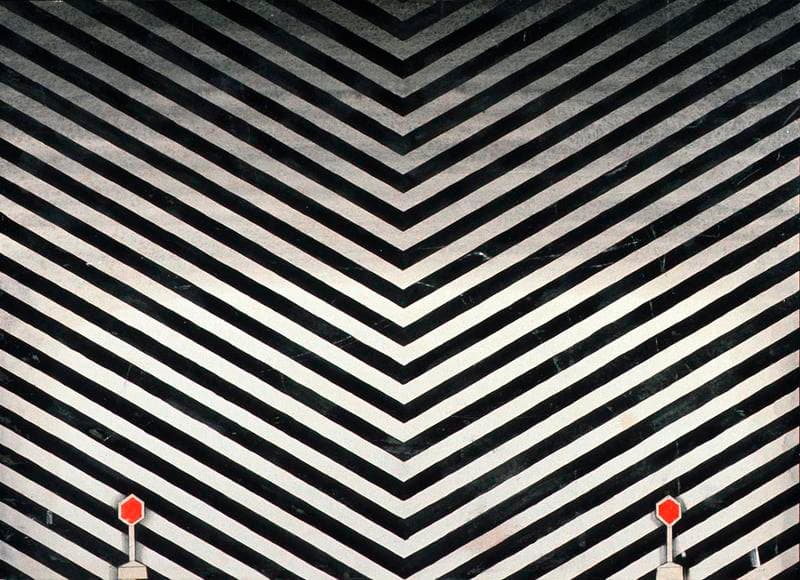

Robert Edmond Jones: Curtain design for Skyscrapers, ca 1926 (San Antonio, TX, The McNay Art Museum)

In Carpenter’s scenario, Scene 1 is Symbol of restlessness, and Scene 2 is an abstraction of the Skyscraper and of the WORK that produces it – and the interminable crowd that passes by. The design is more like a modernist painting – all lines and shadows pointing to a central vanishing point.

Robert Edmond Jones: Scene design with steel girders, scene 2, in Skyscrapers, ca 1926 (San Antonio, TX, The McNay Art Museum)

The transition scenes have their own design – note in all of these images the two red lights that remain permanently on the stage, first appearing with the opening curtain.

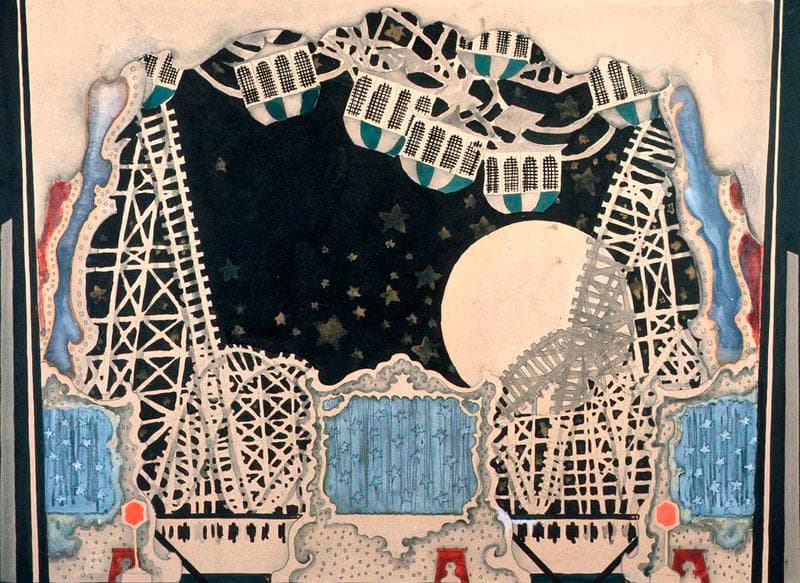

Robert Edmond Jones: Scene design for the Transition from Work to Play, scene 3, and the Return from Play to Work, scene 5, in Skyscrapers, ca 1926 (San Antonio, TX, The McNay Art Museum)

The scenario continues: Scene 3 – The transition from WORK to PLAY; Scene 4 – Any “Coney Island” and a reflection of a few of its manifold activities – interrupted presently by a “throw-back,” in the movie sense, to the idea of WORK, and reverting with equal suddenness to PLAY; Scene 5 – The return from PLAY to WORK and then Scene 6 – SKYSCRAPERS.

Play, of course, takes us to Brooklyn’s seaside fun park, Coney Island, where the steelwork of the city buildings becomes the support for the roller coaster.

Robert Edmond Jones: Scene design for Coney Island, scene 4, in Skyscrapers, ca 1926 (San Antonio, TX, The McNay Art Museum)

The costume designs for the chorus are very different than the extravagant designs for the principals, being more like daily clothes than anything special.

Robert Edmond Jones, costume designs for Skyscrapers (1926). (John Alden Carpenter Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago)

The ballet appeared at the height of the Harlem Renaissance and its music captures the ‘brash, cheeky, quasi-jazzy’ sound of the day. It can be heard in many other works, including Honegger’s Pacific 231, and as part of the music by composers from France and America, including Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, Igor Stravinsky, George Antheil, and George Gershwin. Carpenter’s earlier work Adventures in a Perambulator (1916) included ragtime, popular music of the day, and street songs depicting the day of a child going out for a roll around the neighborhood.

John Alden Carpenter: Skyscrapers (The Dessof Choirs; American Symphony Orchetra; Leon Botstein, cond.)

In his review in Musical America of the premiere, critic Oscar Thompson noted the emphasis on action, starting with those two red lights we noted earlier.

With the parting of the curtains, blinking red lights at either side of the stage represent traffic signals and are “symbols of restlessness”. The backdrop is an “abstraction of the skyscraper.” Girders in abstract confusion; workmen in overalls go through the motions of violent labor while human shadows move meaninglessly by. Suggestions in the music of fox-trotting – rhythms of industry, of building, of working – urgent haste and confusion of city life. Whistles blow, workers emerge and dance toward “any amusement park of the Coney Island type” with its Ferris wheels, street shows, fun-mad, dance-addled crowds – swirling through rhythmic gestures, glorifying American girls’ nether extremities. A more definitely fox-trot rhythm appears, accompanying a lazy, upbeat tune, which is limned clearly when scored for a plucked banjo. There are suggestions of amusement park sounds: brass bands, its carousel, its raucous dance orchestras. The atmosphere is charged with a mixture of febrile gaiety and cloying sentimentality. There is a “flash-back” to the idea of work, with the cessation of dancing, and a return to the workmen swinging their hammers and preparing to rivet. This is followed by a reversion to play in which flappers, sailors, midway types, etc., perform a succession of colorful dances. The next scene brings another transition from play to work, as the workmen leave their dance partners to return to the skyscraper labors, having been summoned by the factory whistle. Gigantic shadows, suggesting a mighty power behind the building of a great city’s skyscrapers, are cast upward against the girders as the ballet concludes.

Even in his review, Thompson seems to be telegraphing his review – short sentences, rushing to the next image! The orchestra, large but standard, did include ‘three saxophones, a banjo, two pianos, celesta, and a compressed air whistle in F sharp’.

The actual motivator behind this extraordinary ballet was, unexpectedly, Serge Diaghilev. He asked Carpenter to write a ballet ‘on the theme of the chaotically energetic American metropolis’. This wasn’t Diaghilev looking forward as much as he was looking over his shoulder. The up-and-coming Ballets Suédois, performing at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, whose ballets looked at contemporary life through dance, was causing Diaghilev concern. The Ballets Suédois had started the race with their 1923 ballet to Milhaud’s La creation du monde.

As he did in Perambulator, Carpenter incorporated familiar music, including music by Stephen Foster and George Gershwin, the minstrel song ‘Massa’s in de Cold Ground’ (by Foster), ‘Yankee Doodle’, Hughie Cannon’s hit ‘Dem Goo-Goo Eyes’, the popular Mexican folksong ‘La Cucaracha’, and other pieces.

The need for the chorus didn’t sit well with Diaghilev and his failure to secure a Met-sponsored American tour by Ballets Russes made him drop the Carpenter’s work. However, the Met was extremely interested in picking it up, resulting in the 1926 premiere.

There’s much in the ballet that seems to still ring true today. One writer looked at the work as an overview, where the ‘scenes of frantic urban crowds rushing to work contrasted with scenes of play in a Coney Island setting, where the world of work recollected intrudes chillingly on the holiday spirit of the weekend’. It all sounds so familiar. At the close, it’s the ‘haunting, quasi-mechanical song of the Skyscraper itself,’ that we hear, trickling through the other sounds of the city: ‘the cries of newsboys, the piercing sounds of jackhammers, and the roar of the city returning to work on Monday morning’.

Although Thompson declared the work to be an emphatic success, it only remained at the Met for another 4 years before being taken out of the repertoire. Thompson’s review called out the importance of Carpenter’s work. He called Carpenter the master of his materials and a composer who was able to create a kind of semi-jazz music, rather than a full jazz that would change the genre too much. In an interview at the time, Carpenter said that to represent current American life without incorporating jazz would be, for an American musician, ‘a difficult, if not a painful task’. It was what was in the air, in the art, and on the stage.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Hello. I am Julio from Spain where i was born. I follow since always the classic music,when i have seen your publication,i have liked It very much. BEST WISHES.