The German town of Donaueschingen is picturesquely located in the Black Forest in the State of Baden-Württemberg. It stands near the two sources of the river Danube, and it started to host a festival for contemporary classical music in 1921. The “Donaueschingen Festival,” as it is called, established a small festival for presenting the works by young and promising artists. The first concert presented the world premiere performances of music by Alois Hába, Ernst Krenek, and Paul Hindemith. Three years later, the festival featured composers associated with the 2nd Viennese school, including Josef Matthias Hauer, Anton Webern, and Arnold Schoenberg.

Anton Webern: 6 Bagatelles, Op. 9, No. 1 “Mässig” (Juilliard String Quartet)

Anton Webern, 1927

And on 19 July 1924, audiences were treated to the premiere performance of Anton Webern’s Six Bagatelles for String Quartet, Op. 9, performed by the Amar Quartet with Paul Hindemith playing viola. The Six Bagatelles emerged as individual pieces between 1909 and 1913. Initially, Webern wrote three sets of pieces for string quartet, with five, four, and three movements respectively. He was looking to publish them as a large group as his Opus 3, explaining, “these groups belong together, and I would like them always to be played in sequence.”

Anton Webern: 6 Bagatelles, Op. 9, No. 2 “Leicht bewegt” (Juilliard String Quartet)

Donaueschingen in 1900

Weber eventually abandoned his initial conception and the pieces became his Five Movements, Op. 5, and Six Bagatelles, Op. 9. When Webern gave a copy of the score to his friend Alban Berg, he wrote “Not much in quantity, but much in content.” A scholar writes, “When Webern and his colleagues abandoned tonality during the first decade of the century, they abandoned an important means of channeling musical tension over large spans of time. Consequently, early atonal works tended to be brief and aphoristic.”

Anton Webern: 6 Bagatelles, Op. 9, No. 3 “Ziemlich fliessend” (Juilliard String Quartet)

The scholar Kathryn Bailey writes, “they are fleeting glimpses, whispered suggestions, breaths… of the air of another planet.” And Schoenberg wrote in the preface for the published score, “Consider what moderation is required to express oneself so briefly. Every glance can be expanded into a poem, every sigh into a novel. But to express a novel in a single gesture, joy in a single breath, such concentration can only be present when there is a corresponding absence of self-indulgence.” And as we can clearly hear in performance, the majority of movements have durations of less than a minute.

Anton Webern: 6 Bagatelles, Op. 9, No. 4 “Sehr langsam” (Juilliard String Quartet)

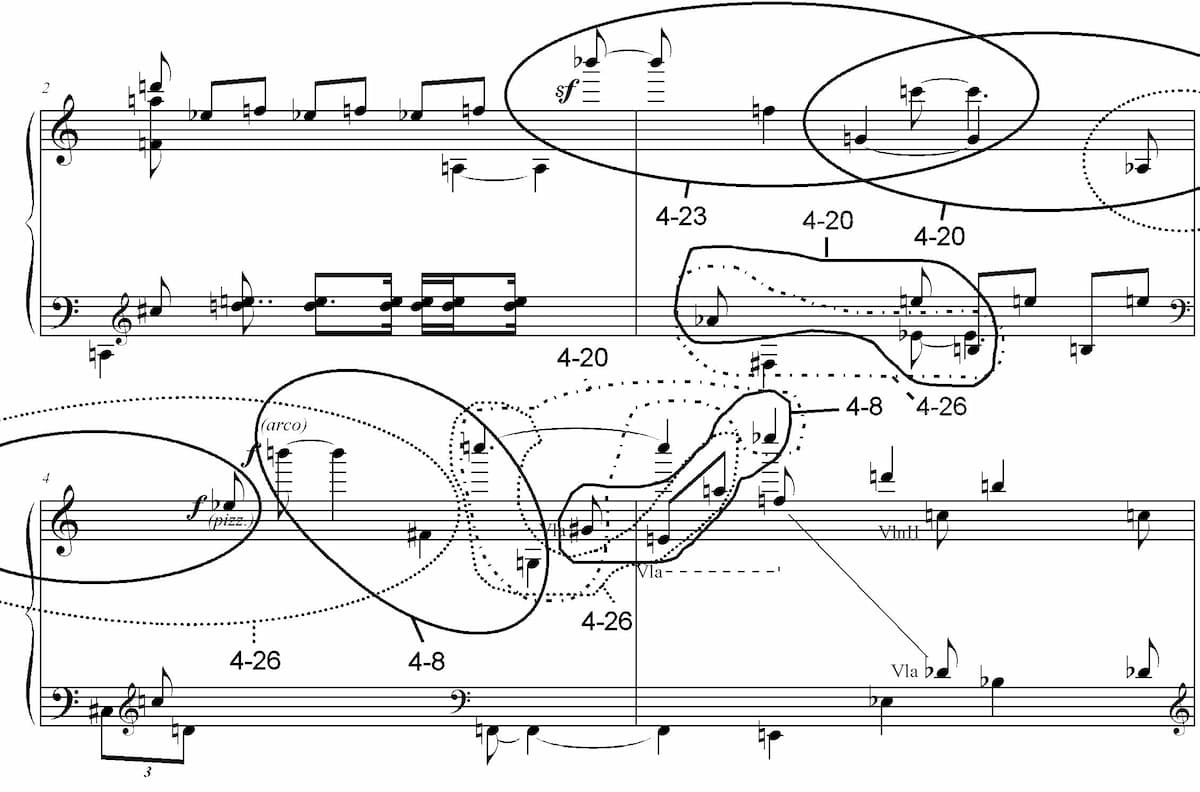

Analysis of Webern’s Six Bagatelles for String Quartet No. 2

A commentator wrote, “These briefest of musical thoughts each have the feeling of a recaptured emotional memory. And each has the promise, through its internal resonance in the sensitive listener, of unlocking a world of self-understanding.” Webern is probably the most analyzed composer in the history of Western music, but the Bagatelles seem to reach beyond any analytical vision. A scholar writes, “It sounds like the end of the world, maybe six different ends, or maybe 6 facets of the same avowal: an identical reclusion into sound.”

Anton Webern: 6 Bagatelles, Op. 9, No. 5 “Äusserst langsam” (Juilliard String Quartet)

Amar Quartet, 1925

For some listeners, the 6 Bagatelles “bring us far into ourselves. Memory, with this format of music, behaves in an erratic manner… It is a music of illusion, of surface, and therefore of reality, of phenomenon.” Theodore Adorno called it a “world of uncertainty, between color and drawing, whereas with Klee, a primal indomitable sweet force takes over the ability to distinguish between shape and background.” The composer himself suggested that the 6 Bagatelles are an attempt of going “against the transient quality of the dimension of the work, as relentless spiritualization forces all sensual dimensions of music to be at the service of expression and latent coherence.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Anton Webern: 6 Bagatelles, Op. 9, No. 6 “Fliessend” (Juilliard String Quartet)