The great composer Dimitri Mitropoulos said in 1951, “I was profoundly shocked to read of the death of Arnold Schoenberg. He was one of the greatest geniuses of our time. He did for music in the twentieth century what Einstein did for science. He created a new musical system and method of expression, which influenced half of the younger generation of composers. Arnold Schoenberg believed in his own destiny. With his death, that belief will be fulfilled.”

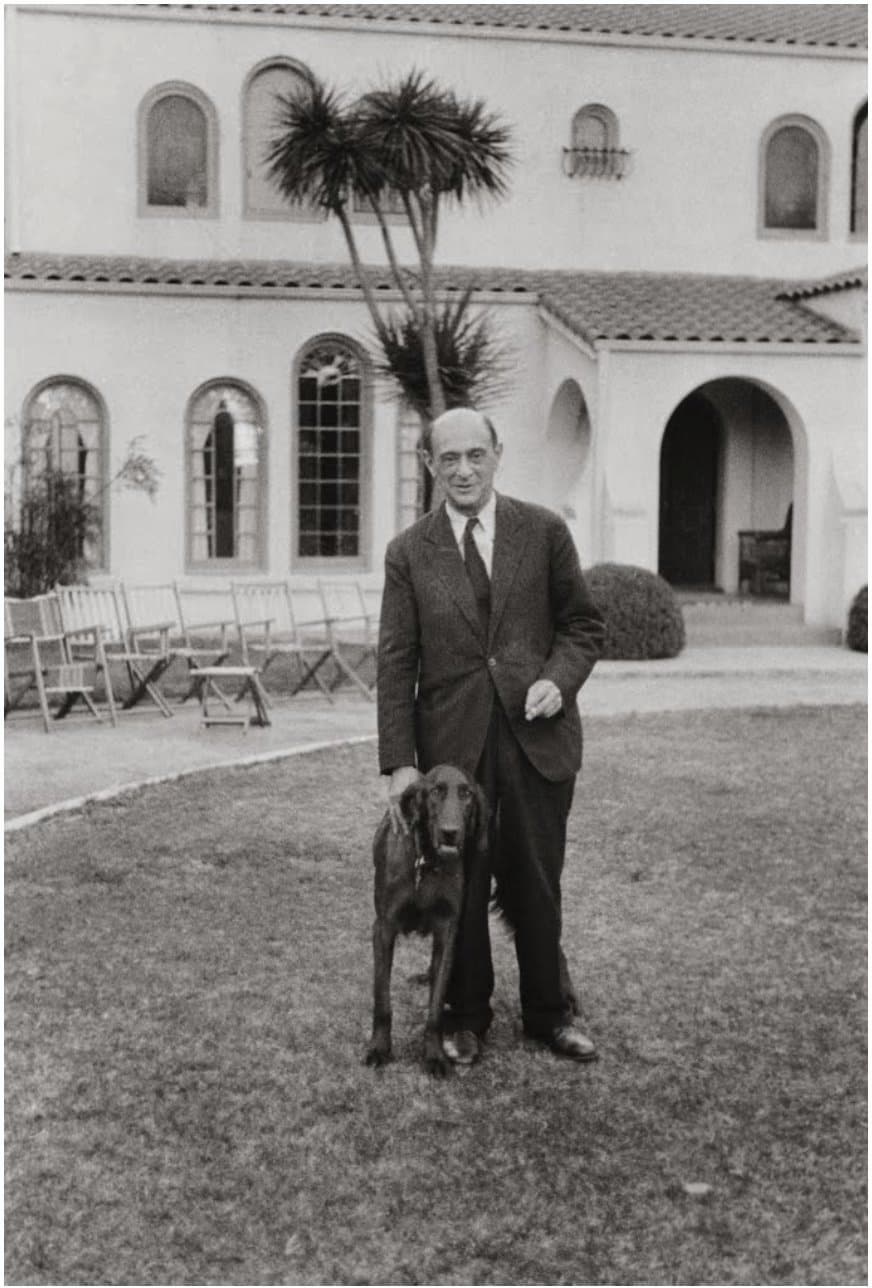

Schoenberg in Brentwood, LA

Arnold Schoenberg was born on 13 September 1874, and he died on Friday, 13 July 1951. In fact, the number 13 became a powerful, all-consuming obsession that influenced not only his personal life but his professional conduct as well. For his birthday in 1939, a year that is coincidently a multiple of 13, Schoenberg asked the astrologer Dane Rudhyar to prepare his horoscope. Schoenberg was told that “the year was dangerous, but not fatal.” In a letter dated 4 March 1939, Schoenberg wrote: “Indeed, I am not so well at the moment. I am in my 65th year and you know that 5 times 13 is 65 and 13 is my bad number.”

Arnold Schoenberg: String Trio, Op. 45

In August 1946, Schoenberg was seriously ill and he received injections for violent pains in the chest. He became unconscious and stopped breathing, and only an injection directly in the heart brought him back to life. “I have risen from a real death and now find myself quite well, “ he wrote to his wife Gertrud. As he would tell Thomas Mann, “my string trio Op. 45 describes my illness and medical treatment.” And subsequently, he showed Hannes Eisler some chords representing injections.

Lawrence, Arnold, Gertrud, Nuria and Ronald Schoenberg

On 2 August 1950, Schoenberg wrote a report on the history of his own illness. He writes at the end, “My asthma has changed somewhat. I do not often have violent attacks, but the condition of breathlessness is more or less chronic. I only feel free from it for four or five hours a day, and every night I awake from lack of breath… For many months I have not dared to sleep in my bed anymore but sleep in a chair.”

Arnold Schoenberg: Phantasy for Violin and Piano, Op. 47

From this report, we do get a detailed insight into the various treatments that had been performed on the composer. “I was treated for diabetes, pneumonia, kidney disease, hernia, and dropsy.” Because of the poor state of his health, his seventy-sixth birthday on 13 September 1950 was celebrated without the usual party. Schoenberg was sensing that his time on earth was coming to an end, and he wrote two wills and testaments in October 1950.

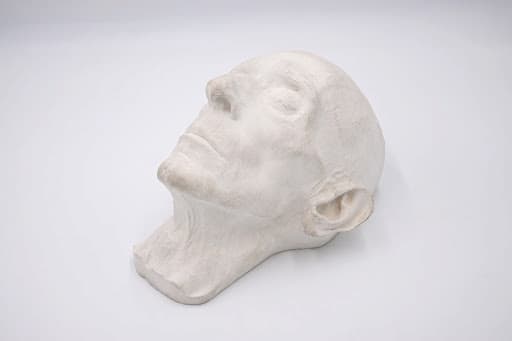

Death mask of Schoenberg by Anna Mahler

Schoenberg approached 13 July 1951 with a great deal of apprehension, and his wife reports. “He has trouble with his foot, and then an indescribable nervousness in his whole body and in his mind. His fear of dying had turned to resignation in the end. He was tired and wanted to die.” When Friday the 13th of July actually arrived, Schoenberg was severely depressed and anxious, and he stayed in bed all day. “Arnold slept restlessly, but he slept. About a quarter to twelve, I looked at the clock and said to myself: another quarter of an hour and then the worst is over. Arnold’s throat rattled twice, his heart gave a powerful beat and that was the end.”

Arnold Schoenberg: 3 Folksongs, Op. 49 (BBC Singers; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

Alma Mahler-Werfel arrived with her daughter, the sculptress Anna Mahler, who made a death mask of Schoenberg. Gertrud recalled, “In the house which had lost its soul all was silent. The workroom with its many books and music scores, the writing table, carved by Schoenberg himself, and covered with paper pencils, notes, and magnifying glasses were no longer needed.”

Schoenberg’s grave of honor in Vienna

According to his wife, “his last word had been harmony.” The funeral took place on 17 July 1951 at the Wayside Chapel in West Los Angeles. “Rabbi Edgar F. Magnin conducted the ceremony, which was attended by 80 mourners.” Schoenberg’s urn remained in the family home when together with the ashes of his wife, they were taken to Vienna in 1974. They were interred in a grave of honor in Vienna’s Central Cemetery, and the Arnold Schoenberg Choir performed De Profundis Op. 50b. Schoenberg’s son Ronald “spoke of a symbol of posthumous appreciation, and Schoenberg’s brother-in-law Rudolf Kolisch, “suggested that much of the injustice done to Schoenberg in his homeland was now buried.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter