Felix Mendelssohn is credited with creating a new genre of music for the piano: the short lyrical pieces known as the Lieder ohne Worte, the Songs Without Words. It was common in the Romantic period to have short lyrical piano pieces, but the genre itself wasn’t named until Mendelssohn made his contribution.

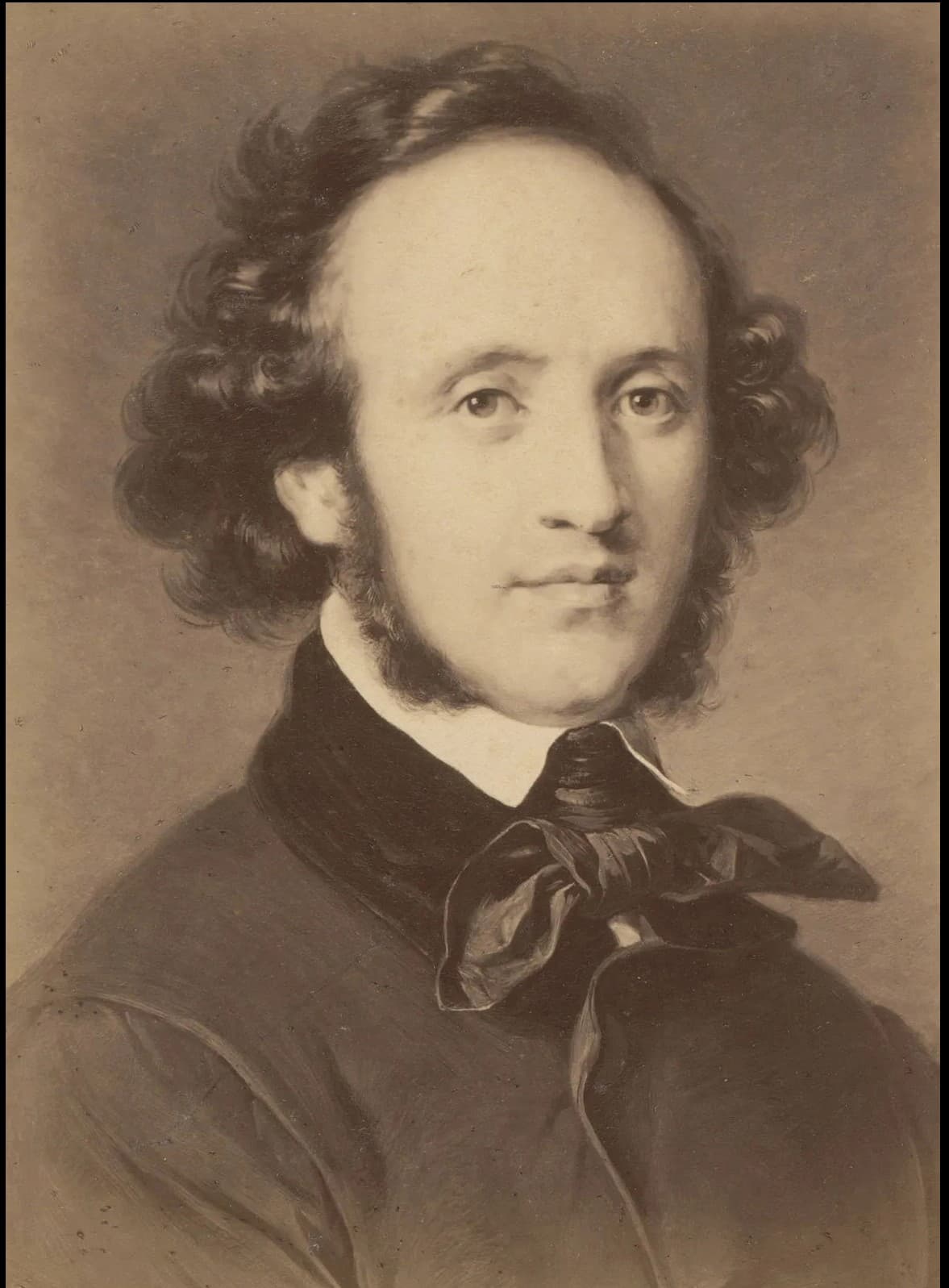

Felix Mendelssohn

His first book of these piano works was originally entitled Original Melodies for the Piano but the new name was too inviting and the whole series (originally 8 books of 6 melodies each), plus some extras, appeared as Songs Without Words. Robert Schumann famously described these works as ‘an art song abstracted for the piano, with its text deleted’.

It is thought that the genre originated in a game Felix would play with his equally talented sister Fanny, where they would compose piano pieces and then add texts to them.

The first book, Op, 19b, was written between 1829 and 1830 and published in 1832. It includes 6 major-key and 3 minor-key pieces. They were intended for pianists of varying abilities so appealed to a wide range of players.

Mendelssohn uses three vocal types in the Op. 19b: the solo song (Nos 1 and 2) where the treble song is supported by an accompaniment below, the part song (Nos 3 and 4) that has a more chordal style, and the duet (No. 6) where the melody is doubled in thirds or sixth. The remaining two pieces (Nos 3 and 5) are really miniature sonata forms.

Mendelssohn only titled the last piece, the Venetianisches Gondellied, written in memory of his trip to Venice in 1830. Its writing, with ‘blurry pedal effects and gently undulating cross-rhythms’ evoke the waters of Venice.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 1, Op. 19b – No. 6 in G Minor, Op. 19b, No. 6, MWV U78, “Venezianisches Gondellied” (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

The second book, Op, 30, was published in 1835 and includes music written between 1830 and 1835. The volume was dedicated to Elisa von Woringen, one of Mendelssohn’s supporters and daughter of a Düsseldorf judge. The last song in this set is another Venetian gondolier’s song.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 2, Op. 30 – No. 12 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 30, No. 6, MWV U110, “Venezianisches Gondellied” (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

Lieder ohne Worte, vol. 3, was published in 1837, and dedicated to Rosa von Woringen, the sister of Elisa von Woringen, dedicatee of vol. 2. No. 3, filled with arpeggios, was written for Clara Wieck (later Clara Schumann), then a mere 18 years old. She made her brilliant Vienna debut in December 1837. No. 5 uses a compound meter and is reminiscent of the agitation in Schubert’s Erlkönig, which had been performed by Mendelssohn in Leipzig in March 1837, a month before he started writing this piece.

Andreas Staub: Clara Wieck, 1839

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 3, Op. 38 – No. 17 in A Minor, Op. 38, No. 5, MWV U137 (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

After a 5-year delay, the 4th volume of the Lieder ohne Worte came out. This volume was dedicated to Sophie Horsley, daughter of the English composer William Horsley; her younger brother was studying with Mendelssohn in Leipzig at this time. As he had in all the preceding volumes, each piece offered contrasting tempos, keys, and textures. No. 5 reflects his travels in Scotland, and he writes in a folk-song style, with some audible connections to his Scottish symphony.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 4, Op. 53 – No. 23 in A Minor, Op. 53, No. 5, MWV U153, “Volkslied” (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

Clara Schumann is the dedicatee of the 5th volume, which was published in 1844. Solo songs (Nos 1 and 6) are joined by another Venetian Gondolier’s song (no. 5), which is written as a duet. It is the last song in the collection, originally entitled Frühlingslied (Spring Song), which is probably the most familiar. The ‘Spring Song’ title was suppressed by Mendelssohn when he published the Op. 62 set, but the title crept out again and was again associated with the piece.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 5, Op. 62 – No. 30 in A Major, Op. 62, No. 6, MWV U161, “Frühlingslied” (Spring Song) (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

Continuing our survey of Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte, 1845 brings us the sixth book of the collection. This Op. 67 collection is dedicated to Sophie Rosen, fiancée of his friend Karl Klingemann. As in the earlier volumes, solo songs (Nos 1, 5, and 6) and duet songs (Nos 2 and 5) contribute to the variety of the album. No. 4 falls outside those song categories. It has a whirling motion that gave its name, the ‘Spinnerlied’ (Spinner song). Yet, this is one of the pieces that actually stands outside the Lieder ohne Worte world because it would be impossible to set any words to this incessant motion.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 6, Op. 67 – No. 34 in C Major, Op. 67, No. 4, MWV U182, “Spinnerlied” (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

Lieder ohne Worte, vol. 7, Op. 85, and vol. 8, Op. 102, were issued after Mendelssohn’s death. He died in 1847 and, although he had done preliminary work in getting these last collections together, it was his publisher, Simrock in Bonn, who determined the contents. Mendelssohn had prepared a manuscript of Sechs Lieder ohne Worte for the artist Ida von Lüttichau of Dresden, and, in the end, Op. 85, Nos 1, 2, 3, and 5 and Op. 102, No. 2 came from that manuscript. The piece that was omitted was issued separately as the Reiterlied (Horseman’s Song).

Ida von Lüttichau

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 7, Op. 85 – No. 37 in F Major, Op. 85, No. 1, MWV U189 (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

The only pieces in the last books to bear a real title are Op. 102, nos. 3 and 5, ‘Kinderstück’. This follows in the tradition of Schumann’s Klavieralbum für die Jugend, for example.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 8, Op. 102 – No. 47 in A Major, Op. 102, No. 5, MWV U194, “Kinderstuck” (Roberto Prosseda, piano)

Through the development of his Lieder ohne Worte, Mendelssohn didn’t wait for publication to distribute the music to his friends, often writing them in his friends’ album books. Then he would revise and polish, capture, and cull the works to create the final published volumes. He was careful to give variety, either through the textures (solo songs or duets), the mode (major and minor), and the key choices (all flats in an abbreviated cycle). His first book, Lieder ohne Worte, Op, 19b, was issued jointly with a Lieder mit Worten, as it were; in this case, Op 19a.

Felix Mendelssohn: 6 Gesänge, Op. 19a – No. 3. Winterlied (Kristina Stobaeus, soprano; Aivars Kalejs, piano)

In a sense, Mendelssohn made the song virtuosic by writing his examples without words. The problem of the singer, who has to breathe, who has to have the correct vowels to have an extended melisma, and other details of vocal performance, are no longer part of the equation. Mendelssohn’s friend Marc-André Souchay tried to put texts to the piano works, but Mendelssohn objected – he thought his music didn’t need the definition that the words might give it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter