Throughout the 19th century, the Rhine was an important symbol in German nationalism. It played a major role in the formation of the German state and spawned wide-ranging cultural symbolisms, including legends, poetry, and musical metaphors. Robert Schumann discovered the river and surrounding lands only in 1850. He had basically lived in his native Saxony all his life, but on 31 March 1850, he accepted the appointment as Düsseldorf’s Municipal Music director. Düsseldorf is located at the confluence of two rivers, the Rhine and the Düssel, a small tributary. Most of the city lies on the right bank of the Rhine, and it is the second largest city of the Rhineland.

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish), “Lebhaft” (Animated)

Robert and Clara in Düsseldorf

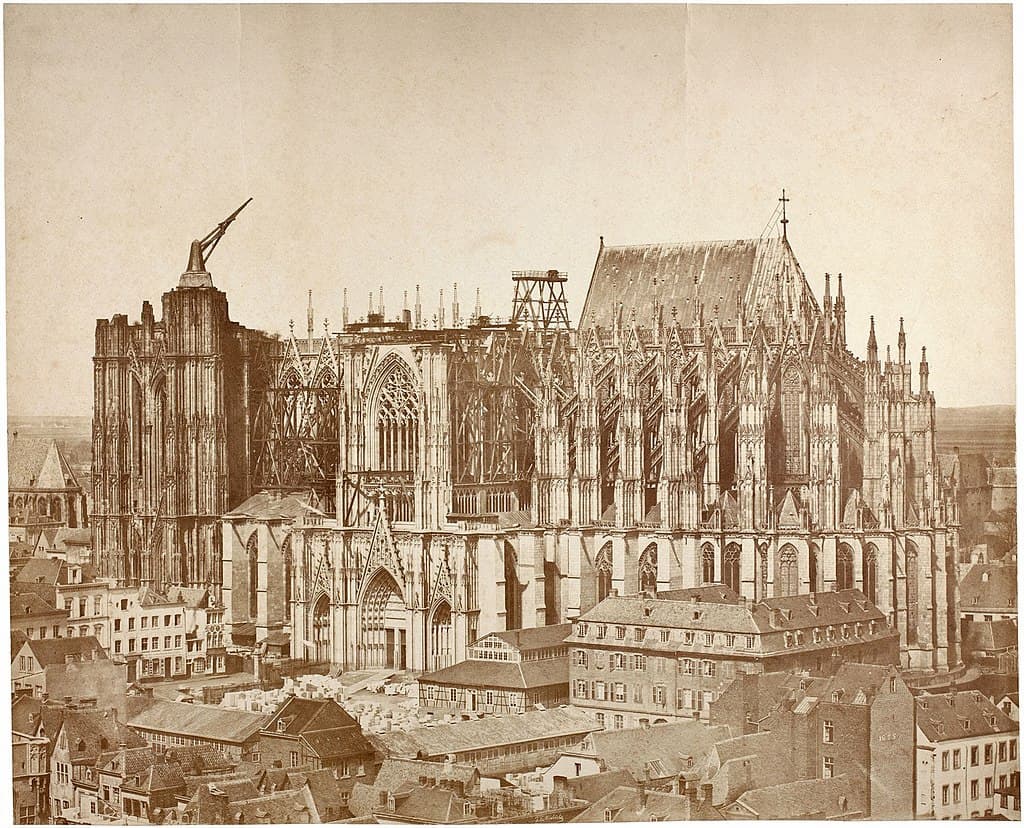

Köln Cathedral on the banks of Rhine

Robert and Clara, along with their seven children, arrived in September 1850, and the city welcomed the new celebrities with commemorative concerts, lavish banquets, long speeches, and grand balls. The Schumanns found the people along the Rhine friendly and welcoming, and the whirlwind of social activities was only dampened by less-than-ideal living conditions. The apartment was located in the middle of the city, and Clara mentions “the incessant street noises, barrel-organs, screaming brats, and wagons.” Robert declared that the noise disrupted his ability to compose, and he thought, “that his bad mood was a result of house anger.” It clearly did not affect him all that much, however, because he composed his Cello Concerto in a matter of days in October.

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish), “Scherzo” (Munich Philharmonic Orchestra; Sergiu Celibidache, cond.)

Euphoric Response to the Rhineland

Robert and Clara Schumann, 1850

At the end of September, the couple took a day trip to Cologne, because Robert had long wanted to see the cathedral there. The largest Gothic building in northern Europe had been partially completed, and Schumann witnessed the installation of Cardinal Archbishop von Geissel. He was much excited by the splendor of the ceremony in the cathedral and vowed to return in November to tour the building again. Shortly after his first visit, he set to work on an orchestral composition that captured his euphoric response to the Rhineland. His Rhenish Symphony was completed on 9 December 1850, and according to Clara, Schumann was inspired to compose the symphony after their “happy and peaceful trip to the Rhineland, which felt to them as if they were on a pilgrimage.” In the event, Schumann’s new symphony reflects his optimism in the face of new challenges, and the “Rhenish” is perhaps one of the most awe-inspiring works Schumann ever composed for orchestra.

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish), “Nicht schnell” (Munich Philharmonic Orchestra; Sergiu Celibidache, cond.)

Public Reception

Cologne Cathedral, 1855

Originally, Schuman gave each of the five movements descriptive titles, but in the end, decided to publish it with simple indications. Schumann was worried that providing an extra-musical program would force a certain opinion of the music upon the listener. As he explained, “If the eye is once directed to a certain point, the ear can no longer judge independently.” And at an earlier date he had suggested “we must not show our heart to the world: a general impression of a work of art is better; at least, no preposterous comparisons can then be made.” Schumann conducted the premiere, as part of his sixth subscription concert, on 6 February 1851. The reception was generally enthusiastic, and “the audience applauded between every movement, and at the end of the work joined the orchestra in congratulating Schumann by shouting ‘hurrah.’”

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish), “Feierlich” (Solemn)

The Not-So-Happy End

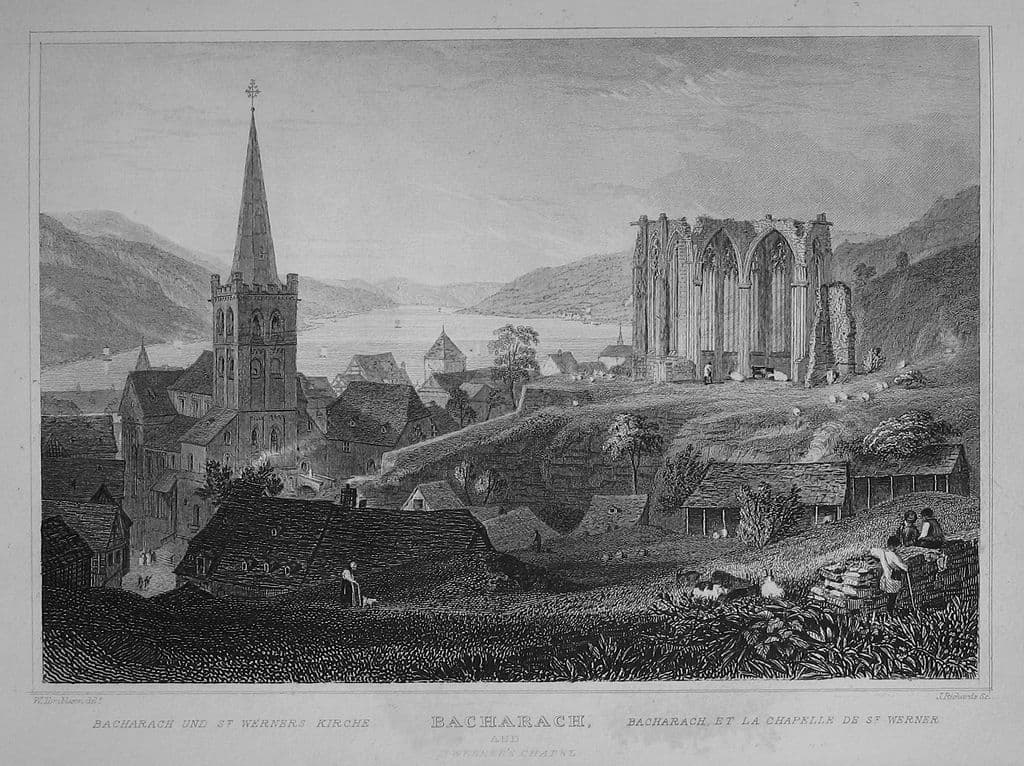

“Views of the Rhine” by William Tombleson (around 1840): Village of Bacharach and ruin of the Werner Chapel

Schumann was pleased, and he conducted a repeat performance on 13 March. However, his enthusiasm for Düsseldorf was short-lived. He could not come to terms with the convivial atmosphere in which concerts took place. Audiences went for drinks and sandwiches in the park surrounding the hall during intermission, and returned at their leisure and frequently in high spirits. Düsseldorf had a small orchestra of roughly 40 players, and musicians were chronically absent from rehearsals and performances. Clara Schumann got into a row with the city, which had not paid her for her appearance as a piano soloist on the program. She bitterly complained about the city’s attitude of “buy the husband, get the wife for free.” And while the joyous Finale marked “Lebhaft” (Animated) concludes one of Schumann’s most original orchestral works, there was no happy ending for Robert. Subject to depression and hallucinations, he threw himself into the Rhine on 27 February 1854.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish), “Lebhaft” (Animated)