One might argue that Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) is perhaps the most exhibited and collected sculptor in the world. His sumptuous bronze and marble figures, including the highly lauded “The Thinker” and “The Kiss,” are masterpieces by what some critics consider “the greatest portraitist in the history of sculpture.” In fact, Rodin is one of the few sculptors widely known outside the visual arts community.

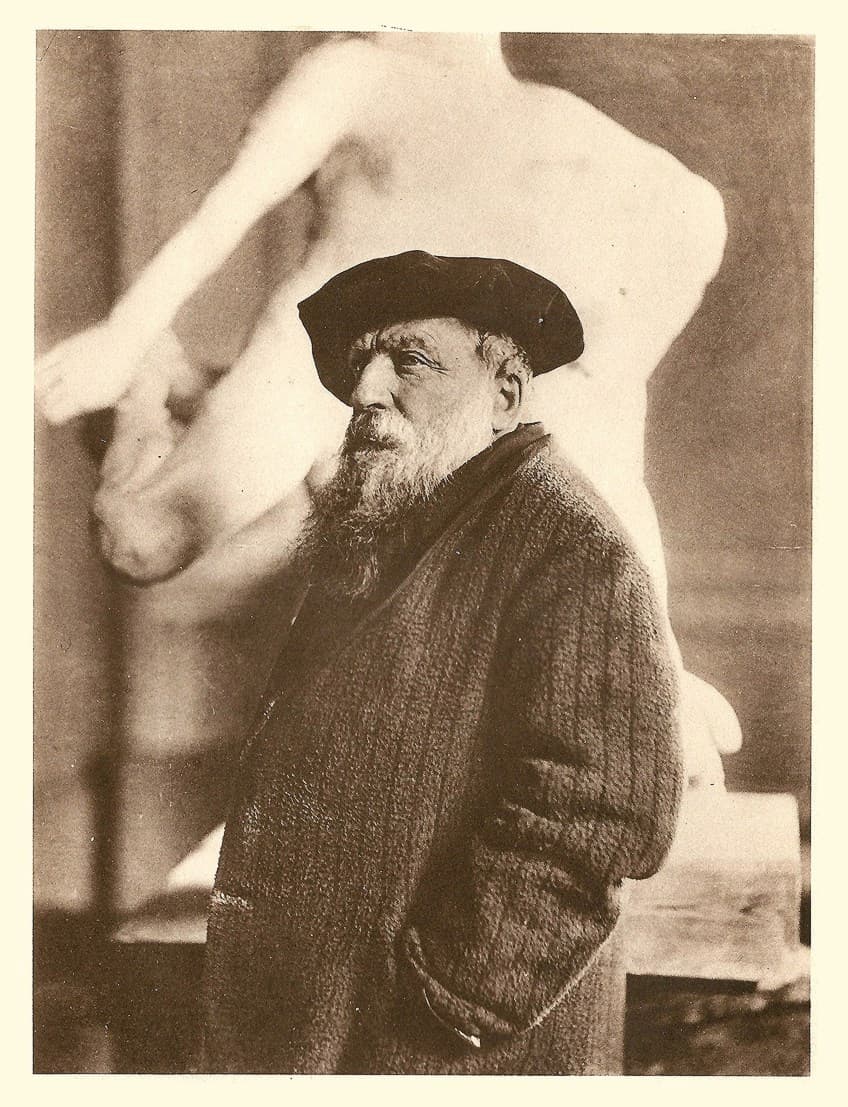

Auguste Rodin, 1910

Rodin is sometimes referred to as the founder of modern sculpture, as he imparted his works with passionate realism. He modeled the human body with great naturalism, and his sculptures celebrate individual character and physicality. Since he departed from traditional themes of mythology and allegory, he was roundly criticized, yet he refused to change his style. Born on 12 November 1840 the son of an inspector in the Paris Préfecture de Police and a former seamstress, Auguste Rodin grew up in a working-class district of Paris known as the Mouffetard. He received his early instruction at the “Petite École,” a school for the training of decorative artists. However, he was rejected by the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts three times and served a long and difficult apprenticeship instead.

Claude Debussy: String Quartet in G minor, Op. 10

Following his third rejection, Rodin worked in a variety of jobs, primarily as a craftsman doing decorative stonework. However, he continued to create sculptures in his spare time, but his first submission to the official Salon exhibit in 1864 “The Man with the Broken Nose,” was rejected. Rodin did discover more lucrative commissions in the studio of prominent commercial sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, but the Franco-Prussian War interrupted stable employment in 1870.

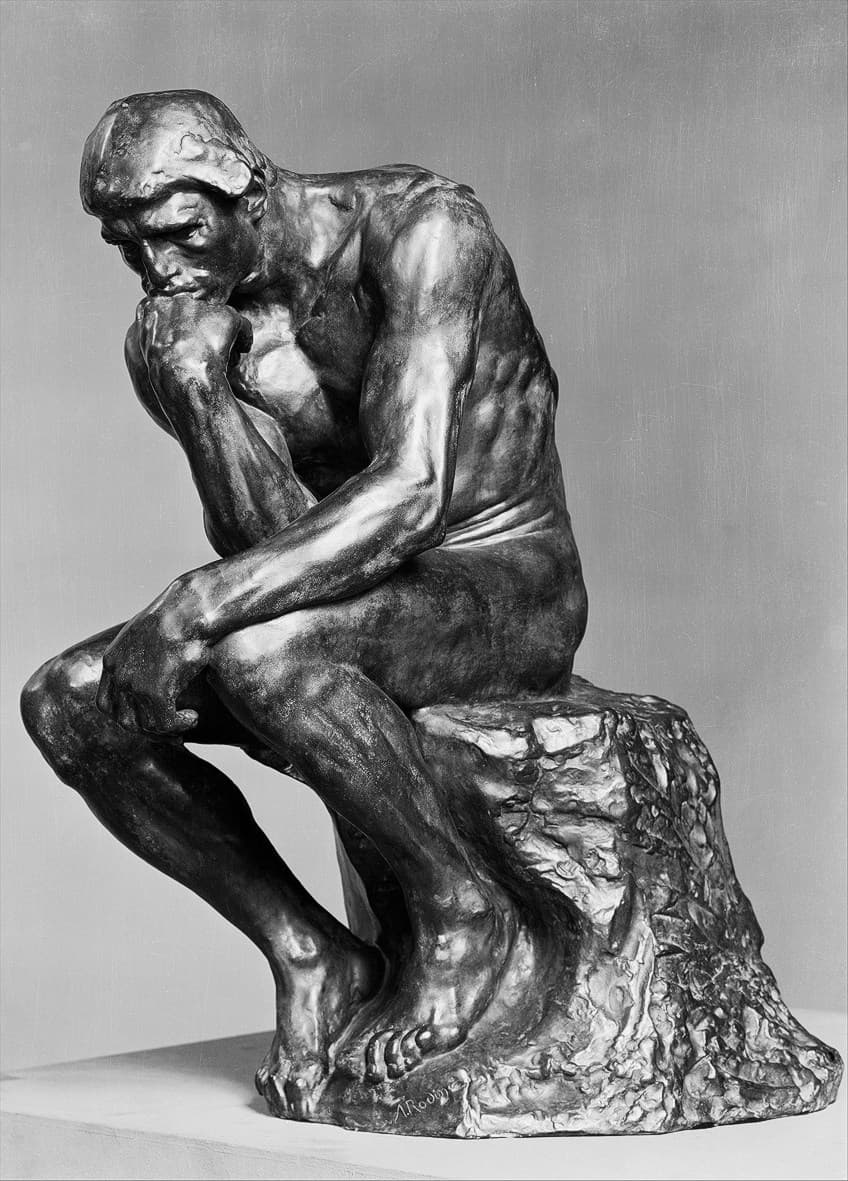

Auguste Rodin: The Thinker

Rodin spent six years in Belgium, and an art historian writes, “At the age of 35, Rodin had yet to develop a personally expressive style because of the pressures of the decorative work. A visit to Genoa, Florence, Rome, Naples, and Venice, and the inspiration of Michelangelo and Donatello gave him the shock that stimulated his genius.” He molded his first original work “The Vanquished,” a painful expression of energy aspiring to rebirth. Exhibited in Brussels and the Paris Salon in 1877 under the title “The Age of Bronze,” it caused a scandal with critics unaccustomed to its powerful realism. In fact, he was accused “of having formed its mold upon a living person.”

Camille Saint-Saëns: String Quartet No. 1, in E minor, Op.112

While “The Age of Bronze” was a controversial figure, it attracted the attention of Edmund Turquet. He was a liberal politician serving in the Chambre des Députés, and in 1879 became Undersecretary of State for fine arts. Turquet offered Rodin a commission for a bronze door to a museum that didn’t yet actually exist. “The Gates of Hell,” although it was left unfinished, it was Rodin’s most important work. The theme of its scenes is modeled after Dante’s Divine Comedy, one that would “reveal a universe of convulsed forms tormented by love, pain, and death.”

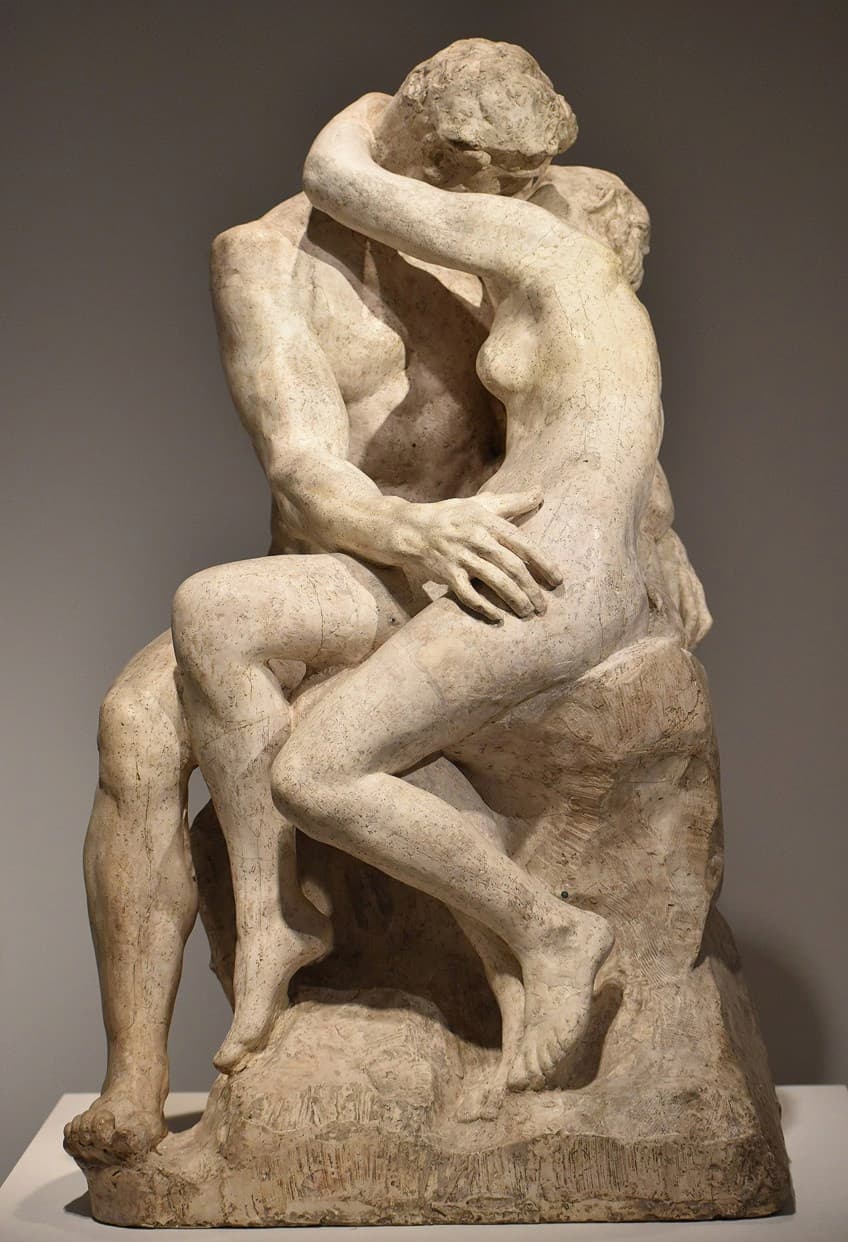

Auguste Rodin: The Kiss

As a scholar put it, “it was the canvas across which would pass the totality of his imagination; it was the surface from which he would draw the creations of an entire career.” In fact, Rodin isolated, modified, and recombined clay models for individual figures and groups of the relief, among them his famous “The Thinker” and “The Kiss.” As his career blossomed, Rodin received further commissions, including a monument of the town of Calais “The Burghers of Calais,” and a memorial sculpture to Honoré de Balzac.

Gabriel Fauré: String Quartet in E minor, Op. 121

Rodin was in his forties when critics began to describe him as “a great artist, perhaps even the best young sculptor in modern France.” The sculptress Camille Claudel, sister of the poet Paul Claudel, started working in his workshop. She became his inspiration and muse, acting as his model, his confidante, and his lover. An art critic described her as “A revolt against nature: a woman genius.” She became the focus of the most overwhelming passion of Rodin’s life, “and the fertile ground that nourished the large number of erotic groups that began appearing in the 1880s.”

Auguste Rodin: The Burghers of Calais

As a critic writes, “his abandonment of the traditional vocabulary of allegorical symbols in favor of individual poses and gestures that reveal character were innovations that brought his work into conflict with accepted formulas.” However, the “Exposition Universelle” of 1900 in Paris featured a pavilion in which 150 of Rodin’s sculptures and numerous drawings were displayed, testifying to the international scope of his fame. Together with Camille Saint-Saëns and the U.S. writer Mark Twain, Rodin was made a doctor honoris causa at Oxford University. He was revered as a modern-day Michelangelo, “a titan of sculpture, in the incarnation of the power of inspired genius.” Rodin exerted an immense influence on sculpture, “in bringing Western sculpture back to what always had been its essential strength, a knowledge and sumptuous rendering of the human body.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Maurice Ravel: String Quartet in F Major

I’ve seen a lot of Rodin’s sculptures, pieces of art around Stanford University/Campus at Stanford Town in California twice.