Arvo Pärt: Lamentate

The Tate Modern in London has one exhibition hall, the Turbine Hall, that is so large it becomes its own problem for artists. The space is 155m x 23m x 115m (500’ x 75’ x 115’) with an exhibition area of 2,200 m2 (35,520 ft2 ). When artists design for the hall, they often say that this is the largest space they’ve ever created work for.

In 2002-2003, the British artist Anish Kapoor (b. 1954) created his sculpture Marsyas for the Turbine Hall. The work is created from 3 steel rings joined together by a PVC membrane. The two rings on the ends are positioned vertically while the one in the middle is horizontal.

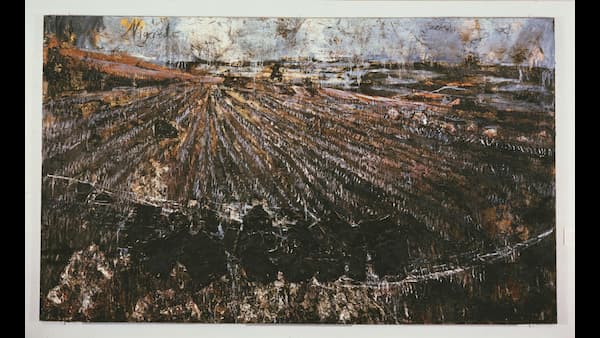

Kapoor: Marsyas, 2002 (London: Tate Modern). The whole structure

The final work was 150 meters long and ten stories high. It was important to Kapoor that the work be so large that it was impossible to get a view of the whole piece. As he noted ‘It is jammed into the building so as to not allow anything but a partial view. The work must maintain its mystery and never reveal its plan’. He wanted the language of engineering to be turned into the language of the body, hence the colour of the work, ‘like a flayed skin’, and the title Marsyas, the name of the Phrygian satyr who challenged Apollo to a music contest.

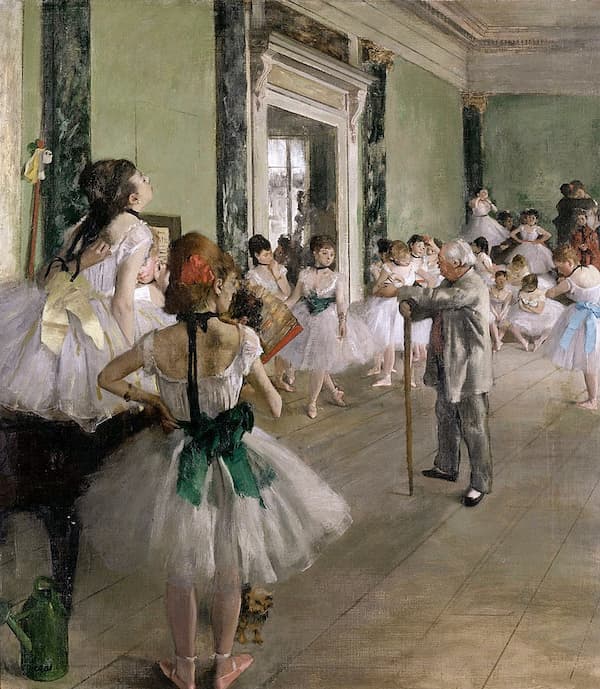

Marsyas and his aulos (a double-reed instrument with two pipes) issued a music challenge to Apollo and his lyre. Marsyas won round 1 but round 2, determined by Apollo, was to play the same music again with the instrument upside-down – easy for Apollo but impossible for Marsyas.

Runeberg: Apollo and Marsyas (Helsinki, Finland: Ateneum)

Another story has Apollo winning when he adds his voice to the lyre, something else impossible for Marsyas to do. In any case, Marsyas lost. His penalty for losing to Apollo was to be flayed alive. The mourning tears of those who mourned him (his brothers, nymphs, god, and goddesses) created the river Marsyas in Phrygia.

There are larger metaphors here beyond string versus wind instruments – we also have the Olympians victorious over the earlier nature spirits that the satyr would have represented, there’s the image of an artist who is great enough to challenge a god but who is defeated through a ruse. Marsyas was also a metaphor for free speech and a symbol of liberty. In Rome in 200 BC, Marsyas represented the common people struggling against the elite. On a more fundamental level, the contest can be viewed as the ongoing struggle between the two aspects of human nature: Apollonian and Dionysian (or rational vs chaotic, order vs chaos, reason vs emotions).

The enormous sculpture inspired Latvian composer Arvo Pärt into considering it both as a lament for the living who must deal with the suffering in the world and also as a musical object, with its brass instrument bell design. The title carries the internal pun on LamenTate, incorporating the name of the museum into the musical title.

In October 2002, when he stood in front of the sculpture for the first time, Pärt said his first impression was ‘powerful’. He went on to say ‘Suddenly, I found myself put into a position in which my life appeared in a different light…. Death and suffering are questions that preoccupy every person born into the world. …Accordingly, I have written a Lamento, not for the dead, but for the living who have a hard time dealing with the suffering in the world.’ Pärt’s work, written on commission from the Tate Modern and an homage to Kapoor and his sculpture, was given its debut on 7 February 2003 in Turbine Hall beneath the work. Pärt saw the work as a confrontation with mortality and created a piece that is both melancholic and classical. The dreamy world of Apollo confronts the ferocious world of Dionysus (or Marsyas) until coming to a conciliatory ending.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arvo Pärt: Lamentate (Ralph van Raat, piano; Netherlands Radio Chamber Philharmonic; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)