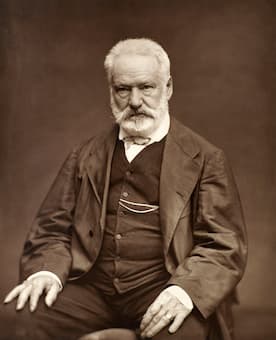

Étienne Carjat: Victor Hugo

In pre-Islamic Arabia the “Jinn” represented invisible spirits inhabiting the earth. Unseen by humans, they are capable of assuming various forms and exercising extraordinary powers. In common Arabic mythology, jinn “are capable of assuming human or animal form and are said to dwell in all conceivable inanimate objects—stones, trees, ruins—and underneath the earth, in the air, and in the fire. They possess the bodily needs of human beings and can even be killed, but they are free from all physical restraints.” Jinn are neither innately evil nor innately good, and they must eventually face salvation or damnation. It is said that jinn “delight in punishing humans for any harm done to them, intentionally or unintentionally, and are said to be responsible for many diseases and all kinds of accidents, while simultaneously providing inspiration for artists.” Representations of jinn frequently appear on charms and talismans, as they are called upon for protection or magical aid. In the fashion of his time, the French Romantic novelist Victor Hugo (1802-1885), author of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Les Misérables, penned a little-known poem about the jinn found in his 1829 collection Les Orientales.

Victor Hugo’s Les Orientals

Set in a North African seaport, the poem describes the horror of an invasion of the town by a horde of evil jinn in an array of frightening shapes. It features a “hideous army of vampires and dragons,” according to the townsfolk, and concludes with their eventual withdrawal. According to Jorge Luis Borges, “With each stanza, as the Jinn cluster together, the lines grow longer and longer, until the eighth, when they reach their fullness. From this point on they dwindle to the close of the poem when the Jinn vanish.”

The first stanza consists of lines of two syllables each, the second three syllables, until a nine-syllable stanza is reached, at which point the stanzas start to contract. In the words of a critic, “the jinns come in a whirlwind, and in a poem shaped like a whirlwind.” The poem describes a pack of Jinn storming a city and their destructive power, and the fear they inspire throughout the entire poem. They are compared to a swarm of locusts aimlessly ravaging everything, sounding the alarm of a city in the throes of urgency in the face of danger. According to scholars, the originality of the poem is due to several elements. “First of all, Hugo relies solely on noise, on hearing, to describe the fierce pack of jinn.

Their night attack allows them to be discerned only when the commotion approaches. Fantasy, mystery, and horror win the reader over to this sound evocation. Here then is the poem in a translation by Robert W. Lebling.

Walls, town

And port,

Refuge

From death,

Gray sea

Where breaks

The wind

All sleep.

In the plain

Is born a sound.

It is the breathing

Of the night.

It roars

Like a soul

That a flame

Pursues.

The higher voice

Seems a shiver.

Of a leaping dwarf

It is the gallop.

He flees, he springs,

Then in cadence

On one foot dances

At the end of a stream.

The murmur approaches,

The echo repeats it,

It is like the bell

Of a cursed convent,

Like a crowd noise

That thunders and rolls

And sometimes crumbles

And sometimes swells.

God! The sepulchral voices

Of the Jinn! What noise!

We flee down the long

Spiral staircase!

My lamp has already died,

And the shadow of the ramp,

Which crawls along the wall,

Ascends to the ceiling.

The swarm of Jinn is passing,

And it whirls, hissing.

Old conifers, stirred by their flight,

Crackle like burning pine.

Their herd, heavy and swift,

Flying in the void,

Seems like a livid cloud,

With lightning flashing at its edge.

They are so near! – Let us keep closed

This room where we defy them.

What a noise outside! Hideous army

Of vampires and dragons!

The beam of the crumbling ceiling

Sags like soaked grass,

And the rusted old door

Trembles, unseating its hinges.

Cries from hell! A voice that roars and weeps!

The horrible swarm, driven by the north wind,

Doubtless, or heaven! assailing my home.

The walls bends under the black battalion.

The house cries out, staggers and lists,

As though, ripped from the soil,

Just as it chases a dried-out leaf,

The wind rolls it along in a vortex!

Prophet, if your hand spares me

From these impure demons of the night,

I would go prostrate my bald forehead

Before your sacred incense burners!

Make their breath of sparks

Die on these faithful doors,

And make the talons of their wings

Scrape and cry in vain at these black windows!

They have passed! – Their cohort

Takes flight and flees, and their feet

Stop beating at my door

With their multiple blows.

The air is filled with a sound of chains,

And in the nearby forests

All the great oaks tremble,

Bent beneath their fiery flight!

The beating of their wings

Fades into the distance,

So vague in the plains,

So faint, that you believe

You hear the grasshopper

Cry with a shrill voice

Or the hail crackling

On the lead of an old roof.

Strange syllables

Still approaching us,

Thus, of the Arabs,

When the horn sounds

A chant on the shore

Rising up at moments,

And the dreaming child

Has dreams of gold.

The funereal Jinn,

Files of death

In the shadow

Hurry their step;

Their swarm rumbles:

Thus, deep,

Murmurs a wave

That no one sees.

This vague sound

That falls asleep,

It is the wave

On the edge;

It is the moan,

Almost extinct,

Of a saint

For a death.

One doubts

The night…

I listen: –

All flees,

All fades;

Distance

Erases

Sound.

Gabriel Fauré: Les Djinns, Op. 12

Winged Jinn

Gabriel Fauré composed his setting of Les Djinns towards the beginning of his career. Why he selected Hugo’s Gothic text for his extended chorus for mixed choir and orchestra (piano) in 1875 is still a mystery. We do know, however, that Camille Saint-Saëns introduced the Hugo poem to Fauré. He might well have believed that the graphic screams of the poetry would result in “powerful and dramatic music appealing to amateur choral societies.” And he certainly took note of the unusual poetic form. Fauré mimics the expanding and contracting verse lines sonically by mirroring the crescendo and diminuendo effect of the poetry. In addition, he transfers the poetic structure and texture into the accompaniment. Not everybody was impressed, and a critic writes, “as with other Hugo settings, the result was not a success, and the original piano accompaniment falls mostly within the silent film villain category.” As the French composer, teacher and musicologist Charles Koechlin observed, the sudden crescendo and change to the major is more pompous and inflated; the excuse of juvenility cannot be put forward, since the Cantique de Racine, as well as some of the songs for the first collection, preserve a character infinitely more in conformity with the master’s personality. Perhaps the most successful passage comes at the end when the breathy alto staccato line from the start returns and the music is imperceptibly altered to vanish into the distance.

César Franck: Les Djinns, Op. 45 (Danielle Laval, piano; Bordeaux Aquitaine National Orchestra; Alain Lombard, cond.)

Hedley Churchward: House of the Jinns © University of the Witwatersrand

Les Djinns, for piano and orchestra by Cesar Franck is virtually unknown, even though his biographers and other writers seem to have held it in high regard. A critic writes, “This beautiful and little-known composition is a musical illustration of a poem by Victor Hugo, describing the emotions of a man pursued by sinister spirits, which approach through the air and gradually increase his terror; he has recourse to prayer; the spirits recede and he is left in silence. The crescendo and diminuendo structure of the poem is followed faithfully by Franck with striking musical effect; the prayer as an expressive cantilena is notably moving. There is no element of superficial virtuosity, which may account for the fact that this sensitive and poetic work has not received the attention it deserves.” The work originated with pianist Caroline Montigny-Rémaury, who asked Franck for a short work for piano and orchestra. It is not known why Montigny-Rémaury refused to perform the work, but the reason might well be found in the work’s symphonic nature.

César Franck

While it features a prominent piano part, it is not really a virtuoso piano concerto. Rather, as a commentator writes, “the spirit of the established virtuoso concerto was set aside for that of the older concertante, and instead of playing a subsidiary and perfunctory accompaniment role, the orchestra became an entity equal in thematic importance to the solo piano. The emphasis was placed upon treatment of the material as well as on piano technique.” Composed in the summer of 1884, the work premiered on 15 March 1885 with Louis Diémer as the pianist at the Société Nationale de Musique. Franck takes up the idea of the mysterious and supernatural forces tearing the nocturnal sky through their passage, and especially the singular rhythm of Hugo’s poem, rising from calm into a sonorous storm, before falling back into the silence of the night. The musical work loosely follows Hugo’s unusual poetic structure as the composer utilizes units of three and six bars in the opening section. Sporting a densely chromatic harmony that relies on frequent dominant ninths and diminished seventh chords, Franck masterfully elides the endings of phrases with the beginning of the next. Franck apparently was thoroughly impressed with Diémer’s interpretation of Les Djinns since he followed it up immediately with his famed Variations symphoniques.

Jules Massenet: Les Djinns

Talisman with Jinn

Jules Massenet is widely considered the most prolific and successful composer of opera in France at the end of the 19th century. However, he also composed a substantial number of smaller-scale works, and more than two hundred songs. Massenet’s choice of poetry shows extraordinary variety, and his musical settings range more than 120 poets who were his contemporaries. In his setting, Massenet was guided by the rules of musical prosody, which necessitates that the text must guide the music, and the musical phrase structure should not contradict or obscure the syntax of its text. In essence, music should in some way express or reinforce the meaning of its text. Massenet presents a detailed and exacting approach to the matter of prosody, focusing predominantly on the melody and rhythm. His innovative déclamation rhythmée, “represents the phonetic, syntactic, and semantic aspects of prosody.” In his setting of Les Djinns the music focuses almost exclusively on the poetic structure, featuring not only a lyrical, tuneful melody in the traditional sense, “but also the prose melody, flexible and free from the traditional square phrase.” According to scholars, “although his songs are pleasing and impeccable in craftsmanship, they are less inventive than those of Bizet and less distinctive than those of Duparc and Fauré.”

Louis Vierne

Louis Vierne composed two symphonic poems on verses by Victor Hugo dating between 1912 and 1914. As France prepared for war, Vierne faced yet another personal crisis. Within a few weeks, all of his students had disappeared; most were mobilized and those too young to fight left Paris with their families. His brothers René and Édouard left for the front and his children took refuge with their mother. Vierne was left alone in Paris, almost blind with neither students nor concerts and no means of earning a living. Fortunately, his friend and student Marthe Bracquemond took Vierne to La Rochelle for the summer. This turned out to be an exceptionally creative time for the composer and in three months he completed the Six Preludes for piano, the symphonic poem Psyché, and his Symphony IV. In Psyché, also based on a poem by Victor Hugo, Vierne is musically searching for the meaning of life, eventually finding it, as the poet had done, in selfless love. Vierne musically offers “colourful and ethereal music, very delicately orchestrated.” Les Djinns, his symphonic poem for voice and orchestra, on the other hand, expresses “a troubled and anguished atmosphere reflecting his own personal crisis.” His student and biographer Bernard Gavoty considered the choice of Hugo’s poem “highly significant, as the composer was fully aware of the difficulties presented by the verbal tour de force of the text. Vierne decided to “bring into play an unfolding drama, including thousand facets of variously colored light.” According to a scholar, “Vierne writes energetic, very well orchestrated music with a rather fantastic atmosphere, best reflecting this unbridled race of evil spirits.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Louis Vierne: Les Djinns, Op. 35