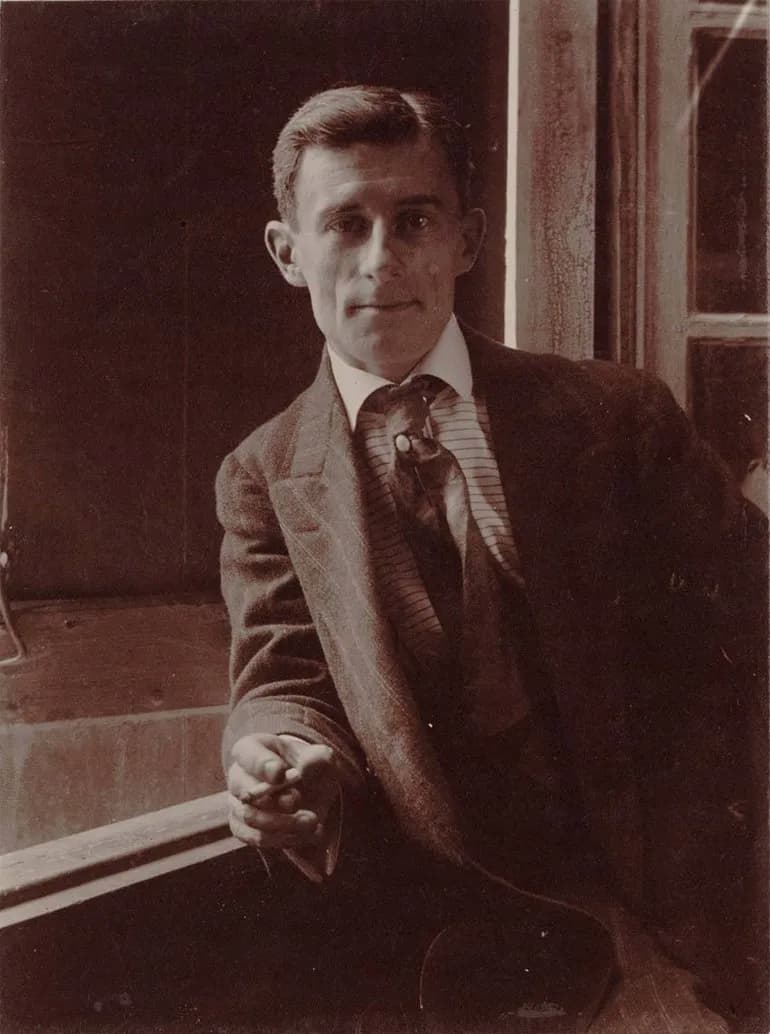

Charles Ives © The Classical Review

The American composer Charles Ives has often been associated with experimental music, or rather advanced music. One does not simply immerse himself in the academic music world through him. Indeed, his works include polytonality, polyrhythm, tone clusters, aleatory elements and quarter tones; devices and musical routes which often privilege intellect over aesthetic — at least from the listener’s standpoint. It is no surprise that Ives ventured into such advanced territories, as the beginning of the 20th century was a fertile period for musical explorations and avant-gardism. As a matter of fact, his active dates almost coincide perfectly with the ones of the leader of the Second Viennese School, Schoenberg, well-known for having broken the rules of dissonance.

Some of the American composer’s most famous works include a symphony — A Symphony: New England Holidays —, depicting the four seasons through American holidays and celebrations, an orchestral set based on American locations— Three Places in New England — and a piano sonata — the Concord Sonata — written after American writers and their works. It is therefore natural that his work for chamber orchestra “Central Park in the Dark” revolves around American themes and places, and expresses some of his most forward thinking musical ideas.

Charles Ives: Central Park in the Dark (Boston Symphony Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

© en.schott-music.com

“Central Park in the Dark”, composed in 1906, is considered as one of the most radical works of the 20th century. Ives describes it as “a piece purports to be a picture-in-sounds of the sounds of nature and of happenings that men would hear […] when sitting on a bench in Central Park on a hot summer night.”

The composer is well-known for his dissonances, however contrary to some other experimental musicians, with this piece it is a matter of exploration serving creativity. It is not so much a question of finding new sounds but rather accurately depicting existing ones, or finding new ways of expressing them. It is thanks to the concepts related to what would become atonal music that Ives is able to break the barriers of tonality in order to provide precision and detail. The listener not only truly sees a musical landscape being painted through his ears, but also feels the air, the ambience, and the surroundings. “Central Park in the Dark” is a work that transcends sensations, feelings and senses.

This unique result is not only achieved by a modern and innovative compositional approach. It is by grouping and placing the instruments in three different and independent groups — all with their own tempi, keys and musical content — that the composer creates a full sensitive picture. Just like real-life sound activities, these groups behave in their own way and at times interlacing each other, at times acting independently. An under-layer is made of the strings that depict the sounds of the night, another layer of winds and percussion interrupts the tranquillity through street parades, and one can even hear a ragtime piano in the apartment next door.

The Second Viennese School © Amazon

Descriptive — or programmatic — music in 1906 is nothing new. It can only feel natural that one would want to reflect his times, and recreate his surroundings. In fact, Vivaldi had been doing this two centuries before Ives, and thanks to that, one can now imagine what living in the baroque Veneto felt like, at least when it comes to sound. But it is a completely different approach that is taken by the American composer. While Vivaldi would not sacrifice traditional rules of harmony for sound accuracy, it is something that Ives not only does, but musically claims; it is how his music is built. A close study of the harmony of the piece reveals polytonality, clashing sounds and tone clusters. More than a musical work, it is a sensitive experience, and in a way extremely accurate and precise. In a few decades, one will be able to imagine and relate to the world of Ives.

Of course, it is difficult not to relate to Messiaen’s works too; with his studies on birds songs, the French composer would bend and rewrite the rules of music as much as needed in order to portray the sounds that he heard. Later, this resulted in him publishing his own theory books detailing his views on music.

Ives has been admired by many of his peers, and Stravinsky said of him that “he quietly set about devouring the contemporary cake before the rest of us even found a seat at the same table”. Once one goes past the apparent difficulty of sonorities in the piece, one can only stand fascinated in front of this work, and its creator’s vision.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Charles Ives: Orchestral Set No. 1, “3 Places in New England” (Boston Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)