200 years ago, on 7 May 1824, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony first sounded at the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna. It was a rather gargantuan event, not at all unusual for a Beethoven academy, as the programme also featured three movements from the Missa solemnis and the overture The Consecration of the House.

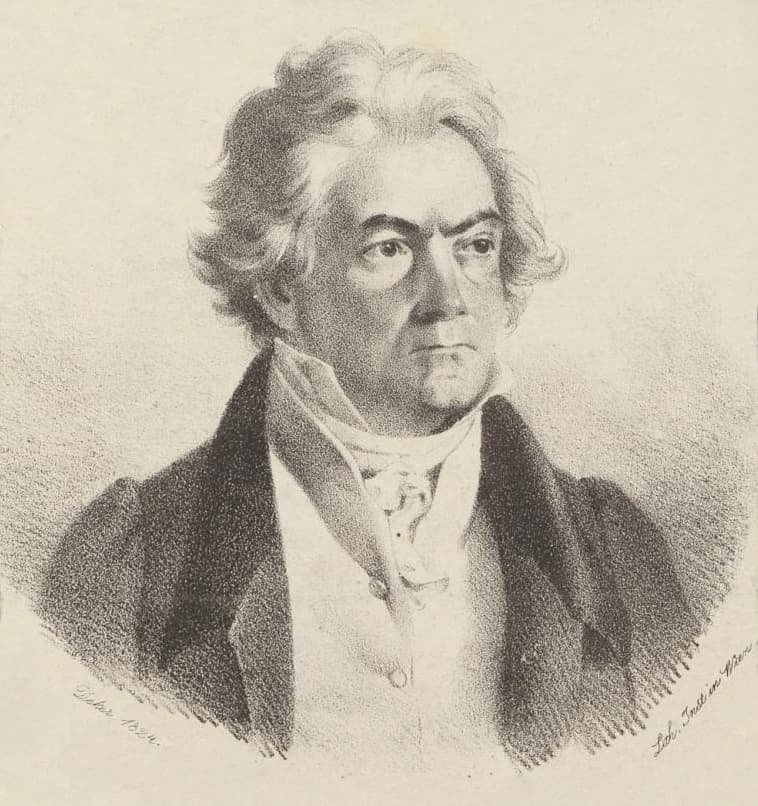

Ludwig van Beethoven in 1824

To commemorate the 200th anniversary of this memorable event, the Beethoven-Haus Bonn has organised an extensive and multi-faceted 10-day anniversary programme. Visitors and enthusiasts, onsite and online, are treated to exhibitions, a book presentation and signing, a conference, various exhibitions, concerts, and livestreams. At the heart of the celebration is the re-creation of the 7 May 1824 concert at the Stadthalle Wuppertal.

Ludwig van Beethoven: “Overture,” Consecration of the House, Op. 124

7 May 1824

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

In 1824, Beethoven assembled a large orchestra and recruited Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger to sing the soprano and the contralto parts, respectively. According to participating musicians, the 9th Symphony had only two full rehearsals, and was prefaced by the Overture Op. 124 and the Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei from the Missa Solemnis. Unsurprisingly, various stories and anecdotes surrounded this momentous occasion. Beethoven, stone deaf at this time, actually took part in the performance by giving the tempos for each part and turning the pages of his score “as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.”

However, the official conductor Michael Umlauf, had instructed the singers and musicians to ignore all of Beethoven’s instructions. When the concert had ended, Beethoven was still conducting and Caroline Unger is credited with turning Beethoven to face the applauding audience. Beethoven’s underlying conception of music as a mode of self-expression still resonates strongly today, and whether one agrees with, or rejects his compositional approach, after him, nothing in music could ever be the same.

Ludwig van Beethoven: “Kyrie,” Missa Solemnis, Op. 123

7 May 2024

Martin Haselböck

200 years later, the complete premiere performance will be reconstructed by the Orchester Wiener Adademie, considered one of the leading period-instrument orchestras. Soloist and the WDR Rundfunkchor under the musical direction of Martin Haselböck invite audiences to the 19th-century historical City Hall in Wuppertal to experience the original programme in its original order and its entirety. This promises a unique and rather lengthy listening experience, and one that will undoubtedly provide a new and unique perspective.

As the Director of the Beethoven-Haus Bonn, Malte Boecker explains, “to mark its 200th anniversary, we are presenting the Ninth for the first time in the sound of 1824 again as well as in the probable instrumentation, the line-up and the programmatic arrangement that Beethoven himself had planned.” Researchers and scholars have been able to reconstruct a number of facts regarding the original performance. Apparently, the choir had been positioned in front of the orchestra and not as we have come to expect, behind the instrumental forces. Additional research has suggested a possible instrumentation described by Beethoven, and important new details regarding the musical text.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9, Op. 125, “Allegro, man non troppo”

Romantic Historiography and Meaning

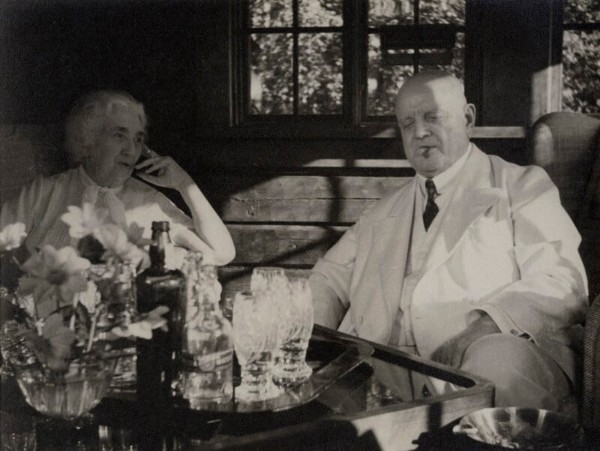

Caroline Unger

According to the organisers of the anniversary concert, “in terms of content and aesthetics, the reconstructed programme shows a variety of relationships and suggests that Beethoven wanted to appeal to the idea of Eternal Peace with the Academies.” By definition, ascribing meaning to a programme and/or a particular work is a slippery subject, as we can interpret Beethoven’s meaning in endless ways. It all depends on our interests as modern reconstructions, while historically informed, are essentially restorations according to contemporary attitudes and tastes.

The recasting of this event in the tradition of terms and meanings is not really a historical project, since the concept of historiography was invented long after Beethoven’s death. It is simply impossible to ascribe a definite meaning to Beethoven’s programme or symphony, nor is it possible to deny the symbolic dimensions of the evening and the work. That is probably why a critic once wrote, “Beethoven’s 9th Symphony is a piece one loves to hate: It’s incomprehensible and irresistible, it’s awesome and naïve.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9, Op. 125 “Molto Vivace”

Berlin Premiere

Henriette Sontag

It might be worth remembering that Beethoven was adamant that his 9th Symphony should be premiered in Berlin and not in Vienna. His threat to take his symphony to Berlin was real enough as it took a petition signed by many prominent Viennese patrons, friends, financiers and performers for the composer to change his mind.

Why then was Beethoven so unhappy with Vienna? For some years the composer had lamented the changing musical taste of Viennese audiences, who numerously flocked to see the operatic entertainments offered by Rossini and other Italian composers. Beethoven and Rossini probably met once in Vienna in 1822, and supposedly Beethoven counselled his young colleague with the words, “Above all, make a lot of Barbers!”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9, Op. 125 “Adagio molto e cantabile”

Ode to Joy

For Beethoven, Rossini was a composer of light comedies, who embraced the “rankest lap of luxury” by pandering to populist demands. Supposedly, Beethoven quipped “Rossini would have been a great composer if his teacher had spanked him enough on the backside.” Whether this meeting and conversation actually took place or not is clearly beside the point, as it quickly became, and still is, part of a much larger narrative.

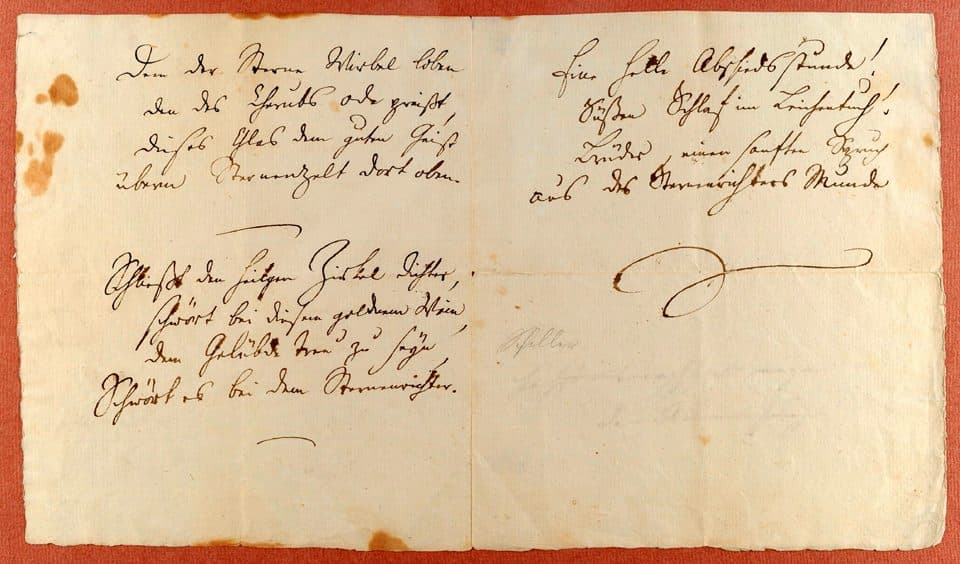

Schiller’s Ode to Joy

By presenting his Ops. 123, 124, and 125 in a single academy, Beethoven was clearly not trying to appeal to popular demands. Rather the opposite, it seems, as a programme of such seriousness, duration and ticket expense, was hardly going to attract the bohemian party crowd. By appealing to the spirit of Romanticism and the shared ideals of humanity as expressed in Schiller’s Ode to Joy, the composer appeared to have made not only a musical point but also issued a decisive cultural statement.

200 years later, the Ode to Joy is the anthem of both the European Union and the Council of Europe. Its described purpose is to “honour shared European values, expressing the ideals of freedom, peace, and unity.” The 2024 re-creation of the 1824 academy still won’t be a crowd magnet, nor will it be an attractive event for most Europeans. However, the statement of intent seems very clear. The utopian ideals expressed in the 9th Symphony, although no longer believable in 2024, still need to provide the fundamental bases of interaction in a world intent on proving the opposite on a daily basis.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter