Since we recently featured the fifteen Shostakovich String Quartets and the seventeen Weinberg String Quartets, I thought it only fitting to reveal some remarkable cutting-edge tendencies in the brilliant Six String Quartets of Béla Bartók, one of the most important composers of the 20th Century. Bartók became a formidable influence on those who followed him.

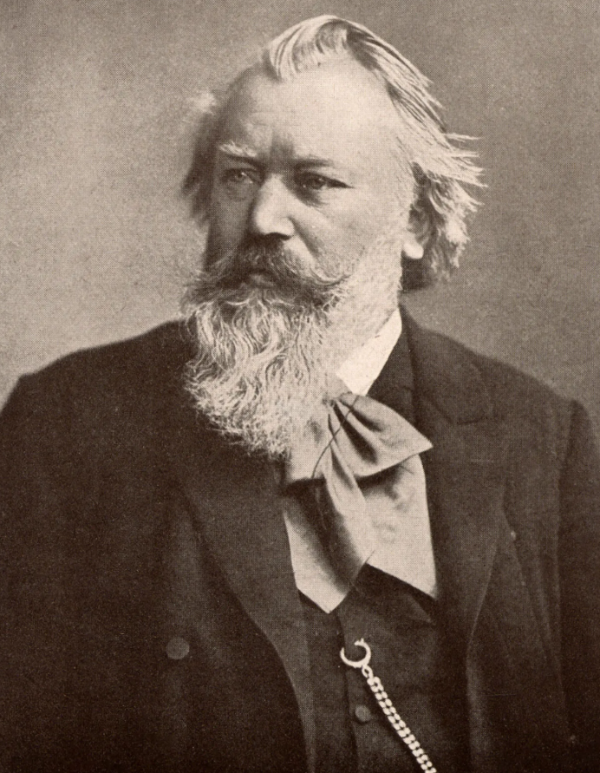

Béla Bartók

I’ve often said that when it comes to the enjoyment of music, the vast majority are pieces both musicians and listeners love, but there are works that audiences love that musicians don’t appreciate playing, and some pieces that musicians adore playing that audiences find challenging to listen to. I would place the works of Bartók in this last category. I think there are a few reasons for that!

If you are entirely new to the music of this composer, consider first reading a previous article, Who’s Afraid of Béla Bartók? as an introduction.

The string quartet genre is considered “the supreme form of chamber music” by Grove Music and others. Beethoven, with his sixteen string quartets, took the form established by Haydn and Mozart, and stretched the genre with amazing innovation, brilliance, drama, and eloquence.

Bartók goes even further. He breaks the mould with new compositional vocabulary, unusual exploration of harmonies, and groundbreaking techniques that are unique and specific to him. He uses whole tone scales and modes, asymmetrical beat patterns, note clusters, and his famous snap pizzicato, a creation of Bartók, where you pull the string upwards (instead of sideways) to make a percussive sound that rebounds on the fingerboard. The quartets span his life and development as a composer—Quartet No. 1 hails from 1908 and incorporates folk elements; the second, composed 1915-17, echoes North African elements of Bartók’s trip there; the third and fourth from 1927 and 1928 respectively are more vigorously dissonant, and the fifth from 1934 and sixth from 1939, make a return to tonality.

There are many interpretations. Every established quartet you can think of has recorded these works such as the Takacs, Végh, Tokyo, Fine Arts, Hungarian, Juilliard, Jerusalem, Budapest, Emerson, and Hagen quartets, to name a few.

To me String Quartet No. 4 in C major from 1928 stands out. It’s riveting, you might even say pivotal and radical. The piece is intensely chromatic, rhythmic, and forward thinking in form. In five movements, the 1st and 5th movements are thematically linked, as are the 2nd and 4th movements. The third movement non troppo, lento seems the focal point. It begins like a Gregorian chant building up to a unique and eerie cluster of notes that are held through a dramatic cello solo. Breathtaking.

The second movement prestissimo, con sordino (played entirely with a mute), is a tour de force for the players. It requires amazing virtuosity and precision.

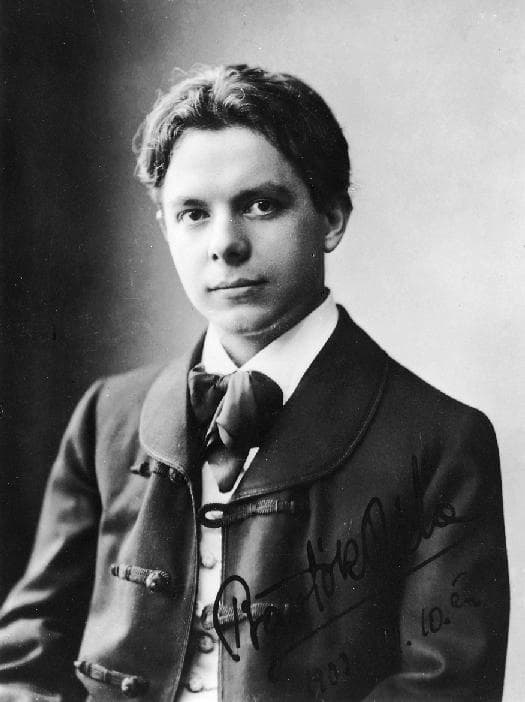

Béla Bartók at age 22

The allegretto that follows is entirely pizzicato or plucked. Ravel also utilized pizzicato for one of the movements of his String Quartet. You’ll hear novel techniques such as the snap pizzicato. There’s also strumming pizzicato, moving one’s hand back and forth like one would on the banjo. Listen and watch the Ebène Quartet play this movement from 16:20 to see these pizzicato techniques, which, by the way, necessitates putting bows down for this movement!

Hang onto your seats for the fifth movement—a propulsive and intense finale. Bartók momentarily puts on the brakes, stopping in its tracks for a charming interlude that recaps themes from the previous movements. The dynamics, textures, and rhythms are pushed to the limits in this movement. Notice the glissandos (slides), some col legno (hitting the string with the stick of the bow), and explosive chords with asymmetrical beat patterns, especially the aggressive offbeats from the cello. Listen from 19:45.

Ebène Quartet No 4

This quartet is full of tone clusters, multiple note chords, pedal tones, and everything in the book to challenge the performers as well as the listeners. We musicians delve into these works with ferocity. To play our own parts, let alone integrate with three fellow musicians, requires a great deal of study and practice. We get to know the music intimately and with a depth that isn’t necessarily attainable in a few hearings.

Another example is the Finale from String Quartet No. 5. In addition to the many unison passages, which require precision and perfect intonation, the extremely fast passagework and unusual rhythms are tremendously difficult to synchronize. Once again, near the end of the movement, there are a few surprises!

Béla Bartók: String Quartet No. 5, BB 110 – V. Finale: Allegro vivace (Végh Quartet)

The String Quartet No. 1, Op. 7, in only three movements, is melodic, and its style seems to imply that Bartók is posing rhetorical questions. During the second movement, Allegretto, the players alternate insistently until an arresting slow section interrupts, poignant and yearning. The movement continues in a rhythmically unpredictable fashion and ends with soothing tranquility.

Béla Bartók: String Quartet No. 1, Op. 7, BB 52 – II. Allegretto (Tokyo String Quartet)

Compare the first quartet with the last. It’s as if the composer stretched himself wandering into new and experimental territory, then returned to tonality with Quartet No. 6. Written at the outbreak of World War II and compounded by the illness of his mother, Bartók made the wrenching decision to leave Hungary for the United States. His own health began to fail.

The third movement from Quartet No 6. Mesto- Burletta: Moderato begins fervently but don’t be fooled. Bartók soon teases with a Burlesque and humor. While it is also irregular rhythmically, it is melodic despite aggressive interruptions, his characteristic pizzicato, and glissandos. The composer also requests the violins to play a ¼ tone flat in places. Somewhat joking in tone, is this a satirical commentary about Hungary’s role during the war?

The exquisite finale marked Mesto, meaning mournful, is deeply expressive and full of longing and pathos. The musicians produce the melodic phrases with long and slow bows, and moments of non-vibrato, to depict the bitterness and disillusionment that Bartók felt.

Béla Bartók: String Quartet No. 6, BB 119 (Hungarian Quartet)

I hope you are now convinced that the Six Quartets of Bartók are cutting-edge, masterfully written, and worth exploring and frequently revisiting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter