Fairy tales normally start with “Once upon a Time,” and generally end with “and they lived happily ever after.” But some of the supposed musical fairy tales I’ve been reading about are not nice stories at all. I am talking about countless young boys who underwent castration for musical purposes. What a ghastly convention practiced almost exclusively in Italy throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Historians tell us, “the taste for castrato voices arose mainly because in large parts of Italy, including the Vatican, women’s voices were not allowed in church.” Since puberty turned choirboys into males and falsettists were considered unsatisfying, the horrid practice began. In a disgusting game of twisting your arm, princely states, leading churches or singing companies approached the parents of a boy who was considered the most talented singer in his church choir. Boys were generally recruited before the age of twelve and from the poorest areas and the poorest families. Since the leading castratos were among the most famous and most highly paid musicians in Europe, it supposedly offered great financial security for many families facing starvation.

Alessandro Moreschi, 1900

Surgeons used minimal anaesthesia while performing the “operation.” On occasion, “a certain quantity of opium was given to persons designed for castration, whom they cut while there were in their dead sleep…but it was observed that most of those who had been cut after this manner died.” If the boy happened to survive the operation, the lack of testosterone made his thoracic cavity developed greatly, “while the larynx and the vocal cords developed much more slowly.” Combined with intensive training, castrati often had unrivalled lungpower and breath capacity. Singing through small and child-sized vocal chords, their voices were extraordinarily flexible and quite different from the equivalent adult female voice. We only have a single sound document to give us a taste of what a castrato voice actually sounded like. Alessandro Moreschi (1858-1922), the last Sistine castrato, was known as “The Angel of Rome” at the beginning of his career. When he made his recordings in 1902 and 1904, he was clearly past his prime, but we still get a fascinating glimpse into the sound world of the castrato.

Alessandro Moreschi “Ave Maria”

Subjecting boys to the “operation” produced a host of different outcomes. A leading scholar writes, “There were high-sopranos, mezzos, and altos, strident voices and sweet ones, loud and mellow voices, more and less flexible throats, very tall men and very short, well and ill-proportioned castrati.” The vast majority of castrati were mediocre or bad singers and became low-level performers traveling between small towns. A very small number, however, reached unprecedented fame, and their abilities had great influence on the development of both oratorio and opera. Let’s go ahead and meet some of the most famous castrati and the repertory they inspired, starting with Giovanni Grossi, nicknamed “Siface” (1653–1697). That particular nickname originated from his stellar performance of “Syphax” in Cavalli’s Scipione affricano in Rome in 1671. He was in the service of the Duke of Modena, and he sang at the opening of the “Teatro Grimani” in Venice. It is said, that his fame even attracted the attention of Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome.

Giovanni Grossi, nicknamed “Siface”

Siface traveled to Paris and London, and a contemporary witness reports. “I heard the famous singer, the Eunuch Cifacca, esteemed the best in Europe and indeed his holding out and delicateness in extending and loosing a note with that incomparable softness, and sweetness was admirable: For the rest, I found him a mere wanton, an effeminate child; very coy and proudly conceited.” His beautiful voice was sadly contrasted by his bad temper, arrogant behaviour, and volatile temperament. Like Alessandro Stradella, “Siface” was murdered for an indiscreet affair, about which he foolishly boasted. When Siface traveled between Ferrara and Bologna, where he was engaged to sing, he was killed by musket fire at the hands of assassins hired by the woman’s family. The murder created a great scandal, and the Duke of Modena made sure the guilty party was held accountable. Siface’s voice was long remembered; in 1741, he was still “famous beyond any, for the most singular beauty of his voice.”

Francesco Cavalli: Scipione affricano, “Hora si ch’assai più fiero” (Filippo Mineccia, counter-tenor; Nereydas; Javier Ulises Illán, cond.)

Nicolo Grimaldi, nicknamed “Nicolini”

The famed alto castrato Nicolo Grimaldi, nicknamed “Nicolini” (1673–1732) was considered the leading male singer of his age. The critic and musicologist Charles Burney described him as “a great singer and still greater actor.” Joseph Addison called him “the greatest performer in dramatic music that is now living or that perhaps ever appeared on a stage.” Born in Naples, Nicolini sang in Naples Cathedral and the royal chapel from 1690. He frequently appeared in opera and, during his early career, was primarily associated with Alessandro Scarlatti. In fact, he sang in the premières of Scarlatti’s La caduta de’ Decemviri (1697), Il prigioniero fortunato (1698), Arminio, L’amor generoso and Scipione nelle Spagne (1714), Tigrane (1715) and Cambise (1719). He took part in thirty-six productions in Naples and thirty-four in Venice, and countless composers created roles for him.

When Nicolini went to London in 1708, he became partly responsible for the increasing popularity of Italian opera in London. He made his England début at the Queen’s Theatre in Haym’s arrangement of Scarlatti’s Pirro e Demetrio. That performance was a huge success, and he signed a three-year contract with Owen Swiney. He sang in all the operas during that period and also sang the title role in the first performance of Handel’s Rinaldo. Until the age of 50, Nicolini “followed the pattern typical for star castrati.” Instead of retiring, however, Nicolini began to take on characters whose age approximated his own. Between 1727 and 1731, all new roles specifically written for him were typical tenor roles. These roles helped Nicolini “to conceal his vocal liabilities—shortness of breath, diminished range and sound quality—as they lent themselves to situations in which characters express passions such as vengefulness, disdain, imperiousness, reproachfulness or remorse.” In 1731, Nicolini was engaged to sing in Pergolesi’s first opera Salustia, but he died during rehearsals.

Alessandro Scarlatti: Tigrane, “Sussurrando il venticello” (Elizabeth Watts, soprano; The English Concert; Laurence Cummings, harpsichord/cond.)

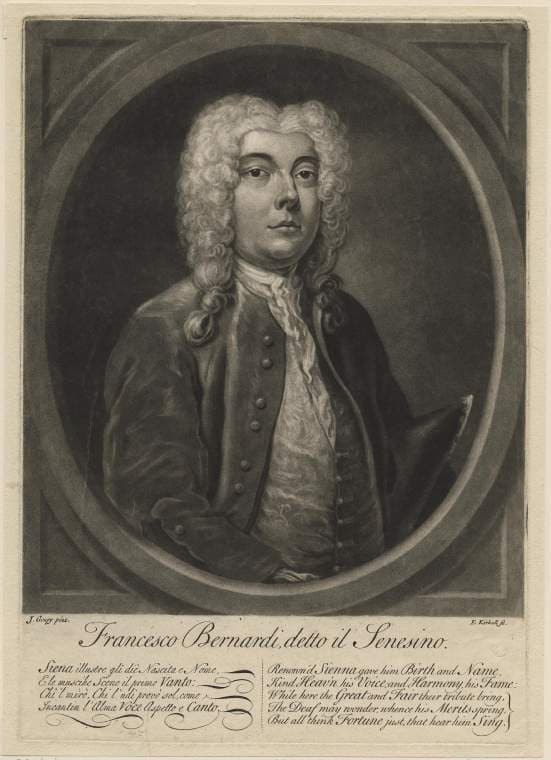

Francesco Bernardi, nicknamed “Senesino”

Francesco Bernardi (1686–1758) was born in Siena, and his nickname “Senesino” was derived from his birthplace. He became one of the most acclaimed castrato singers of his day, and his vocal ability was described in some detail. “He had a powerful, clear, equal and sweet contralto voice, with a perfect intonation and an excellent shake. His manner of singing was masterly, and his elocution unrivalled. Though he never loaded Adagios with too many ornaments, yet he delivered the original and essential notes with the utmost refinement. He sang Allegros with great fire and marked rapid divisions from the chest in an articulate and pleasing manner. His countenance was well adapted to the stage, and his action was natural and noble. To these qualities, he joined a majestic figure.” Senesino initially toured a huge number of Italian theatres and was engaged for Dresden in 1717. He commanded a huge salary but was fired for insubordination in 1720. Apparently, he refused to sing one of the arias from Heinichen’s Flavio Crispo, and tore up the part.

George Frideric Handel, who had been scouting Senesino, brought him to London and engaged him for his company. Senesino joined the Royal Academy of Music for its second season in September 1720. He made his début at the King’s Theatre on 19 November in Giovanni Bononcini’s Astarto and remained a member of the company until June 1728. Senesino sang in all 32 operas produced during this period, and that included seventeen leading roles composed by Handel. Senesino was a superstar, and described as “beyond Nicolini both in person and voice… and beyond all criticism.” The relationship between Handel and Senesino was frequently stormy, as “one was perfectly refractory; the other was equally outrageous.” By all accounts, Senesino’s character was “marred by touchiness, insolence and an excess of professional vanity.” It is reported that he insulted Anastasia Robinson at a public rehearsal in 1724, “for which Lord Peterborough publicly and violently caned him behind the scenes.” Senesino’s tantrums and intrigues were largely responsible for the split with Handel in 1733. In the event, his musical qualifications were superb. He was renowned for “brilliant and taxing coloratura in heroic arias and expressive mezza voce in slow pieces.” Apparently, he had no equal in the pronunciation of recitative, and he “was unsurpassed in accompanied recitatives.

George Frideric Handel: Muzio Scevola, “Spera che tra le care gioie di bella pace” (Jakub Józef Orliński, counter-tenor; Il Pomo d’Oro; Maxim Emelyanychev, cond.)

Giacinto Fontana, nicknamed “Farfallino”

Giacinto Fontana (1692–1739), nicknamed “Farfallino,” was primarily active in Rome between 1712 and 1736. Apparently, he specialized in singing soprano female roles, and was said to have had a high-pitched and small boyish voice. Rather feminine in appearance, he is known to have portrayed an occasional pregnant primadonna. It was his graceful stage appearance that probably earned him his nickname “Little Butterfly.” Graceful stage appearance aside, he seemed to have had a somewhat violent temper, as he almost fought a duel with another musician behind the scenes. “The music he sang does not suggest extraordinary technical abilities,” but he nevertheless created roles in operas by Bononcini, Scarlatti, Vivaldi, Vinci and the later works of Francesco Gasparini.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Leonardo Vinci: Catone in Utica “In che t’offende” (Valer Sabadus, counter-tenor; Il Pomo d’Oro; Riccardo Masahide Minasi, cond.)