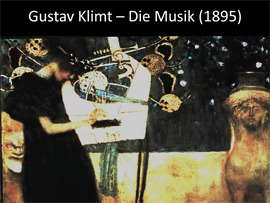

Gustav Klimt started his career as architectural decorator just as the Ringstrasse program of monumental building entered its final phase – in fact, he had been hired to decorate the interior staircase of the Fine Arts Museum. He subsequently became the portrait painter of Vienna’s rich and famous. Just as the young architects had objected earlier to the historicism of the Ringstrasse buildings, Klimt and his fellow artists now also refuted the established traditions of academic painting, in order to create the art of their time, searching for a new message and a new language, which became known as the Vienna Secession. The Secession building by Josef Maria Olbrich became their temple of art, a refuge for the art lover, and the inscription on the left side of the building, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), became their motto – art forever to be renewed – no longer just an imitation of an ancient past. Over the entrance, within the gilded oriental decoration, are the entangled heads of the Medusas which emphasize the instinctual, irrational elements in art. The instinctual becomes the subject of Klimt’s painting ‘Die Musik’ (Music). Here, the young girl, depicted as tragic muse, is playing the kithera — instrument of Apollo, god of light and music — but her song is Dionysian (Friedrich Nietzsche had used the same symbols in The Birth of Tragedy). On her left side is Silenius, the drunken companion of Dionysos, and on her right, the Sphinx, the child-eating mother, symbol of terror and female beauty – representing buried instinctual forces.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy as well as Sigmund Freud’s just-published ‘Traumdeutung’ (Interpretation of Dreams – 1899) were widely read by, and inspired the Secessionist artists, in particular, Max Burckhard, a Nietzschean, who was the director of the Burgtheater and the co-editor of the Secession’s journal, Ver Sacrum. In Nietzsche’s view, the concept of the self, the ‘I’ is a literary ‘I’, constituted in and through language; Nietzsche’s aphorisms – fragments – are to be seen as such and are not to be seen in reference to a ‘whole’ — the world is a text.

For Sigmund Freud, the self and the ‘I’ become the subject of his dream analysis which also shows us a textual construct, the language of dream itself. Freud not only uses literature to make his points, but he was also aware of similar interests expressed by the young contemporary writers of his time, e.g., Hugo von Hofmannsthal (who wrote many librettos for Richard Strauss) and Arthur Schnitzler. In a letter, Freud congratulates Schnitzler on his insights into the psyche of man. In Schnitzler’s ‘Traumnovelle’ (dream novella), the protagonists move constantly between dream and reality, which become fused in the reader’s mind (this work was the basis for Stanley Kubrick’s last film ‘Eyes Wide Shut’), — leaving interpretation wide open.

Klimt received a commission from the city for murals depicting Philosophy, Medicine and Jurisprudence. His interpretation of Philosophy can be seen as an illustration of Nietzsche’s ‘Drunken Song of Midnight from ‘Also sprach Zarathustra’, (which Gustav Mahler had used as the center of his Third Symphony):

| O Mensch! Gib Acht; Was spricht die tiefe Mitternacht? Ich schlief und schlief Aus tiefem Traum bin ich erwacht; Die Welt ist tief. Und tiefer als der Tag gedacht Tief ist ihr Weh – Lust – tiefer noch als Herzeleid; Weh spricht: Vergeh! Doch alle Lust will Ewigkeit — Will tiefe, tiefe Ewigkeit | Oh man, take heed: What does the deep midnight say? I was asleep, asleep From a deep dream I woke The world is deep Deeper than the day has known Deep in its woe – Desire – deeper still than a heartbreak Woe speaks: Go die! |

Klimt’s Philosophy shows an entranced priestess with wine leaves in her hair — Nietzsche’s drunken poetess — surrounded by floating, entangled bodies, a vision that Vienna’s establishment found repugnant; philosophy was supposed to be a rational affair. Medicine and Jurisprudence were considered offenses against public morals. Klimt’s nomination for a professorship was withdrawn as, interestingly, was Sigmund Freud’s.

Click here for more about Beethoven 9th.

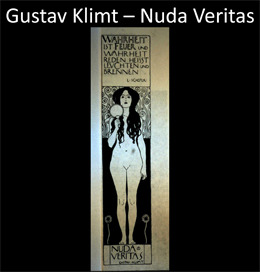

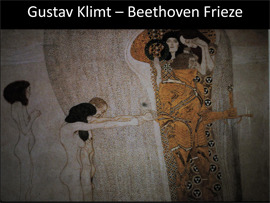

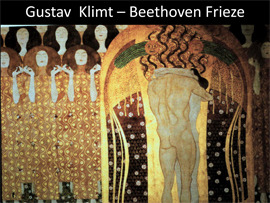

In 1902, Klimt painted his Beethoven Frieze for the 14th exhibition in the Secession building, entirely dedicated to Beethoven, which brought together many of the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops), such as Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser and Max Klinger. The exhibition was planned as a celebration of the composer. Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze takes as its inspiration the chorus of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (Gustav Mahler contributed to the opening of the exhibition with a special condensed arrangement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony). A knight in shining armor is shown on a journey through a world of human foibles — sickness, madness, death, lust and wantonness — ending with an embrace, joyfully acknowledging the brotherhood of man (also Beethoven’s vision in his chorus “Seid umschlungen Millionen…” – Be embraced, oh Millions) and finding redemption in art. Again, Klimt’s depiction was not at all what the good burghers of Vienna understood and wanted to see in their art – theirs was a rational, scientific and orderly world, represented by ‘Pallas Athena’ – the Greek goddess of wisdom. Klimt had designed a poster for the exhibition showing his ‘Pallas Athena’ — ‘Nuda Veritas’ (Naked Truth) – the two-dimensional figure of a young woman, sensual and erotic, to be understood as a concept, not a concrete realization, turning the mirror towards the viewer, who now can inscribe whatever he sees as the truth. The inscription above her reads: ‘Wahrheit is Feuer und Wahrheit Reden Heisst Leuchten und Brennen’ (Truth is Fire and to Speak the Truth Means to Shine and Burn).

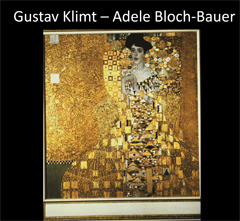

Klimt withdrew from public commissions and became the painter of the haut monde, turning to society portraiture, and to painting women, such as his mistress, Adele Bloch-Bauer. She is shown as wholly cut off from nature, seemingly imprisoned in the stiff Byzantine opulence of her surrounding decoration — only her beautiful face and elegant hands seem to speak of a delicate soul captured in this sea of gold. The glittering design of her clothes and place flatten her body into two-dimensionality. The metallic setting, the delicate detail of symbols, circles, rectangles and triangles reduce her to a beautiful object in a beautiful picture. Klimt, like Yeats, was ‘Sailing to Byzantium’:

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enameling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake:

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

Klimt escaped to the Orient, but with his earlier works, he had opened up new worlds of psychological experience which remained for the next generation of artists, including Kokoschka, Schiele and the Expressionists, to explore.

Click here for more about Mahler’s ‘Das Lied von der Erde’.

Turning to music, Gustav Mahler’s composition, ‘Das Lied von der Erde’ also takes the form of an escape as its subject matter. His ‘song-symphony’, as he called it, continues a new form of music — voice and orchestra, which he had already introduced in his Second, Third, Fourth and Eighth Symphonies, — breaking the traditional form of music composition just as the Secessionists had in the fields of art and literature. Mahler had taken Hans Bethge’s volume of ancient Chinese poetry, translated into German, ‘Die Chinesische Flöte’ (The Chinese Flute) as inspiration, but it, contrary to Mahler’s symphonies, is a complete song-cycle, integrating song and symphony. Drunken exaltation — the wine in a golden cup — calls to us. But ‘Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod’ (Dark is life, dark is death) — the ever repeated refrain in the first part (Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde), which leads through Loneliness (Der Einsame im Herbst) , through Youth (Von der Jugend) and Beauty (Von der Schönheit), then again to the Drunken Man (Der Trunkene im Frűhling) and to the final Farewell (Der Abschied) – ‘endless, endless’, is sung like a mantra until the voice fades into silence .