Leonard Slatkin conducts Shostakovich and Beethoven: 2 Ninth Symphonies

Orchestre National de Lyon, The Gulbenkian Choir, Manuela Uhl, Bea Robein,

Christian Elner, Morten Frank Larsen

29 June 2012, Auditorium de Lyon

Watch the concert

credit : http://www.gardenofpraise.com/

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, “Choral” (1824)

Philharmonia Orchestra

Herbert Von Karajan

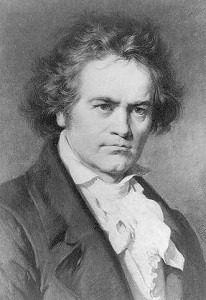

The two respective Ninth Symphonies by Ludwig van Beethoven and Dimitri Shostakovich have long had the unenviable task of representing monuments to the persistence of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

By the year 1814, Beethoven had become profoundly deaf, unable to perform in public, unable to hear music, and unable to talk with friends except by means of conversation books, in which his friends would enter their questions and comments. This silence, which had slowly enveloped the composer beginning in the late 1790’s, halted the enormous productivity of his heroic period, and led to four years of almost complete inactivity, during which his depression found outlet in his rage over the guardianship of his nephew Carl. Around the year 1819, Beethoven slowly reengaged and began to compose the monumental pieces of his late period. These include an extraordinary collection of string quartets and piano compositions, the Missa Solemnis, and most notably the Ninth Symphony. Composed on commission from the London Philharmonic Society, the work was first performed in Beethoven’s last large concert at the Kärntnerthor Theater on 7 May 1824. Details of the premiere tell much about the nature of the Ninth Symphony, and also how it shaped an extended and somewhat divergent reception history. “The composer, his back to the audience stood at the edge of the orchestra to give the tempo at the beginning of each movement. Then the orchestra played, ignoring any further instructions from the composer, because he was completely deaf. When the last movement ended, Beethoven could not hear the thunderous applause of the listeners, and so the soprano soloist, Caroline Ungher, touched the composer on the sleeve to make him turn around. At that point the concertgoers, realizing that Beethoven could not hear them, waved handkerchiefs to show their admiration”. Since then, the composition has been examined from every possible musical, musicological, theoretical and journalistic angle, and I am sure the new critical wave of interdisciplinary synergies will find ways of expanding this essentially positivist line of discourse. Concordantly, it has been called “ Musical Kitsch in the Grand Style” and criticized for an Enlightenment message of universal brotherhood that fails to resonate with historically informed listeners in the 21st Century.

credit : http://lommerte.wordpress.com/

Symphony No. 9 in E flat major, Op. 70 (1945)

Munich Philharmonic Orchestra

Sergiu Celibidache

For Shostakovich, his Ninth Symphony was clearly intended as a celebration of the impending victory of Russian forces over Nazi Germany, or in less sophisticated terminology, the victory of good over evil by the glorious Red Army. As the composer proudly declared on the occasion of the 27th anniversary of the Revolution in 1944, “undoubtedly like every Soviet artist, I harbor the tremulous dream of a large-scale work in which the overpowering feelings ruling us today would find expression. I think the epigraph to all our work in the coming years will be the single word ‘Victory’.” Originally it was envisioned to be a grand affair, featuring orchestra, soloists and chorus, which prompted the scholar Boris Schwarz to quip “ a work that out-Mahlered Beethoven”. In the end, however, Shostakovich decided against such monumental ambitions. “When the war against Hitler was won”, recalled Shostakovich, Stalin went off the deep end, like a frog puffing himself up to the size of an ox, and I was supposed to write an apotheosis of Stalin. I simply could not…”. The result of this change of direction produced a work of “transparence and lightness with Mozartian themes in which a bright mood predominates”. Although initially praised by his Soviet colleagues—Stalin would almost certainly have reacted unkindly to being musically called a puffed-up frog — the work was soon criticized for its “ideological weakness and its failure to reflect the true spirit of the people of the Soviet Union.” Western media, in turn, declared the work trivial and childish, and it was not until the very late 20th-century that scholars discovered the work’s overtly ironic message.

While Beethoven’s Ninth is almost universally heard as a triumph of humanity, the Shostakovich Ninth — and just about everything else he wrote — is exclusively placed within the political context of dealing with Stalin. Although some people would have us believe that these are the only two valid ways of listening to these works — probably the same bureaucrats in Brussels who have somewhat naively adopted Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” as the new instrumental European anthem, obviously forgetting that the janissary march in the concluding movement has its origins in Turkey and that Iberian and French influences are somewhat lacking — it’s merely a point of narrow associations getting in the way of actual musical exploration and interpretation. Maybe Beethoven said it best in the mysterious opening to the first movement, with horns and lower strings in tremolo holding “open fifths”. This primordial void teleologically gives rise to one of Beethoven’s most personal essays. We may follow Beethoven’s lead, sympathize with its message — whatever that may be — or merely reject or react against it. Yet, this open fifth might spur our own imagination and allow us to experience the music in highly personal terms, never forgetting that today’s performance will be shaped by Leonard Slatkin’s interpretation! This kind of musical ventriloquism will assure — none withstanding the constant and rapid changes in musical taste and social conventions — that Classical music will stay alive and vibrant for centuries to come.