Comforting Stories of Persevering Classical Musicians Despite Hardship and Struggles

The common image of the struggling artist started with Mr. Ludwig van B. We all know the story of him overcoming his disability to create some of the most uplifting and inspirational masterpieces in music. But we don’t have to be necessarily rich and famous to struggle with adversity; it’s called life, and we all do. So we’ve decided to put together some very human stories of how creativity in music can become a source of strength, comfort, and inspiration.

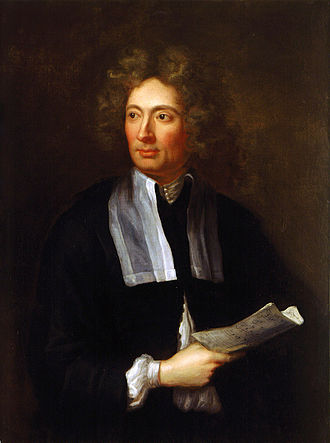

Arcangelo Corelli

Arcangelo Corelli

In these times of great suffering, anguish and misery, we all need some comforting stories from the world of classical music. The Italian composer and violinist Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) suffered from frail health and infirmities throughout his live. He was a humble, mild and moral man who was only rarely capable of participating in public life. It is believed that he suffered from depression, anxiety and long period of melancholy. He only lived three weeks past his sixtieth birthday, but his music is a glorious expression of a positive attitude towards life, hardship and adversity.

Arcangelo Corelli: Concerto Grossi, Op. 6, No. 7 (Anna Holbling, violin; Quido Holbling, violin; Ludovit Kanta, cello; Daniela Ruso, harpsichord; Capella Istropolitana; Jaroslav Krček, cond.)

Louis Braille

Braille music summary

Louis Braille (1809-1852) was blinded in both eyes as the result of an early childhood accident. Nevertheless, he excelled in his education and began to develop a system of tactile code that could allow blind people to read and write quickly and efficiently. He wrote, “Access to communication in the widest sense is access to knowledge, and that is vitally important for us if we the blind are not to go on being despised or patronized by condescending sighted people. We do not need pity, nor do we need to be reminded we are vulnerable. We must be treated as equals – and communication is the way this can be brought about.”

Louis Braille

Louis Braille was also a cellist and organist, and his passion for music soon inspired him to extend his system to include braille musical notation. He published the first book on braille in 1829, and titled the volume Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them. Braille’s passion and love for music overcame his personal disability to bring hope and resilience to all of humanity.

Aaron Jensen: Poems in Braille (Andrea Koziol, vocals; Kajak Collective, choir)

Allan Pettersson

Allan Pettersson

The Swedish symphonist Allan Pettersson (1911-1980) had a miserable childhood. He grew up as the youngest of four children in extreme poverty. His father was a violent, alcoholic blacksmith, and Pettersson once said, “I wasn’t born under a piano… My father was smith who may have said no to God, but he never said no to alcohol.” Living with constant physical abuse alongside social exclusion, he also suffered from his mother’s pious and strict religious attitudes. Coming to terms with his childhood, Pettersson wrote “24 Barefoot Songs” for voice and piano in 1943-1945. The texts are by the composer and reflect his longing for a “more beautiful life.” Sadly, the beautiful life never materialized for Allan Pettersson. In the early 1950s he was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, which kept him housebound from 1968 until his death in 1980. Despite his constant pain, continued extreme poverty and social isolation, he composed 15 large-scale symphonies that elevated him to be one of the most important Swedish composers of the 20th century.

Allan Pettersson: Symphony No. 9 (Norrköping Symphony Orchestra, Christian Lindberg, cond.)

Max Reger

Max Reger, 1890

The German composer and organist Max Reger (1873-1916) was extremely rebellious, and constantly in conflicts with authority. He even joined a youth gang and terrorized other people. He smoked excessively and roamed drunk through his hometown of Wiesbaden. Experiencing restlessness and insomnia, he did acknowledge the dangers of alcohol, but he was not capable of drinking moderately. He even joined the military in hopes of controlling his alcoholism, but his delirious excesses under the influence of alcohol led him to be admitted to the military hospital as a psychiatric patient. The only thing to save him from himself was the process of composition. He furiously composed numerous works, but still was unable to function in any kind of social setting. Mentally, apart from cyclothymic hypomania, depressive symptoms dominated his behavior. He showed anxiety, sensitivity, naive and violent contractibility, warmth, harshness, fidelity, honesty and endurance. He only seems to have been free of his demons when he was working on a composition. And that, to me, is what the therapeutic and transcendental power of music is all about.

Max Reger: 4 Tone Poems after Arnold Böcklin, Op. 128 (Klaudyna Schulze-Broniewska, violin; Frankfurt Brandenburg State Orchestra; Ira Levin, cond.)