It’s difficult today to imagine how one would feel as the first woman member of the New York Philharmonic or any orchestra for that matter. At age thirty-one, in 1966, Orin O’Brien won the position and joined this illustrious group, which was then a bastion of men.

The New York Philharmonic was founded in 1842, but for decades, it was inaccessible to women. Like several orchestras in Europe, a female couldn’t even audition. It was not until 1922 that the orchestra hired harpist Stephanie Goldner who became the first female member. After a decade with the group, she resigned, leaving the orchestra all-male once again, and an astonishing thirty-four years later, when O’Brien was hired.

One doesn’t “land” a position like that without a lot of preparation. Like many of us, O’Brien perfected her craft for years as a young person and then was active as a performer prior to winning her audition for the Philharmonic. She’d performed with the New York City Ballet, the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, and the American Symphony with Leopold Stokowski and as the latter’s principal bass, she played the poignant double bass solo from Alberto Ginastera’s Variaciones Concertantes during the U.S. premiere in 1962.

Alberto Ginastera: Variaciones concertantes, Op. 23 – XI. Ripresa dal tema per Contrabasso (Israel Chamber Orchestra; Gisele Ben-Dor, cond.)

Naturally, her ascendence so many decades ago caused a stir. A 2023 interview with O’Brien and Javier C. Hernandez of the New York Times mentions some of these curious comments.

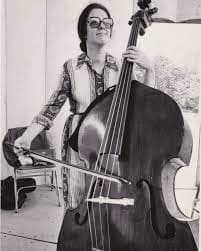

A double bass

According to a 1966 Time Magazine article entitled “Ladies’ Day”, the journalist called her “as curvy as the double bass she plays.” Continuing quite tongue-in-cheek, the author describes the women who were entering the ranks of orchestras at that time. “As it is, Orin struggled through ten years and several auditions before she finally won the job this year over 33 male bass players. Rare Birds. Elsewhere in the U.S., lady musicians are having a heyday. The Cleveland Orchestra now has 11, the San Francisco 17, the Houston 25 and the American Symphony 44. Trombonist Betty Glover, 43, adds class to the brass of the Cincinnati Symphony; Helen Taylor, 24, plays a mean English horn for the Houston Symphony. The rare bird in the Los Angeles aviary is Barbara Winters, 28, who, to produce the needed penetrating sounds from her oboe, must pit her trim 120 lbs. against male fellow oboists who average a burly-chested 200 Ibs.”

Even the venerable New York Times published similar flippant comments (by writer Allen Hughes), “Orin O’Brien, a new member of the New York Philharmonic’s double bass section, is no gentleman. In fact, this O’Brien is not even a man. As the picture to the right attests, Miss O’Brien as comely a colleen as any orchestra could wish to have in its ranks.”

© Orin O’Brien Personal Archive

At the beginning of her tenure, O’Brien rarely had a separate dressing room, and even in my day when I joined the Minnesota Orchestra, that was a rarity. Sexist comments were ubiquitous. O’Brien’s colleagues volleyed a steady stream of asides, and she remembers her chagrin when she was singled out. She just wanted to be in the background. That’s why playing the bass appealed to O’Brien in the first place. Double bassists can be anonymous. Moreover, playing an instrument can be an escape from our troubles. O’Brien’s parents George O’Brien and Marguerite Churchill were Hollywood movie stars, and they were absent from her life much of the time. But when she practised, she could soar to another dimension where she wasn’t overlooked or lonely.

O’Brien retired from the orchestra in 2021. Now at age 88, O’Brien’s story is presented in the Netflix documentary “The Only Girl in the Orchestra . She reflects on her storied career of 55 years in the orchestra. In the background is a wonderful soundtrack with several bass lines from the classical repertoire, including Mahler Symphony No. 2, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A major second movement (in a bass quartet version):

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 – II. Allegretto (Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra; Stanisław Skrowaczewski, cond.)

And the muted, brooding, and ominous bass solo from Verdi’s opera Othello. Listen to Timothy Cobb, Metropolitan Opera bass virtuoso, as he explains how to approach the solo.

Verdi — Otello: Tutorial with Timothy Cobb, Double Bass

Verdi – Othello – Double Bass excerpt

All her life O’Brien had avoided the limelight, but her legacy, and breaking a glass ceiling was recognised.

Still, it took years to convince the camera-shy bass player to agree to the film by Orin’s niece, producer and director Molly O’Brien, an Emmy-award-winning filmmaker. Molly indicated that her aunt had always been one of the adults she admired most, a life that she hoped to emulate. Only the prospect that the film might bring more people to classical music, and to an appreciation for the double bass convinced O’Brien to go ahead with the project.

The film, though only 30 minutes, is an intimate portrait. There are many humorous moments but also poignant ones. The filmmaker shows when O’Brien moves out of her long-time home, the apartment where she’d lived for decades. We see movers dismantle her Steinway piano and O’Brien’s misgivings, we observe as she instructs people how to carry her beloved collection of basses away, and we catch glimpses of the sadness and nostalgia of leaving her position, her colleagues, and her friends. Most of all, we understand her deep love for the sound of the bass and her wish to pass her legacy on to the next generations.

O’Brien is a much-beloved teacher. We watch as she works with students at her apartment and at the Manhattan School of Music and understand that she has inspired generations of bass players.

© Orin O’Brien Personal Archive

The sentiments are beautifully captured, and they resonated with me, even though I left my orchestra position after ‘only’ 32 years. In this short film, they convey how when one plays in an orchestra, it becomes a second family. The camaraderie and friendships that are formed are the result of the intense schedule of music-making, the challenges of difficult repertoire, the travel together, and always trying to attain the highest standards of excellence. It’s an irreplaceable experience. And what a privilege to interpret the music of the greatest composers, new and old, that are some of the greatest creations of mankind.

In an interview for Strings Magazine with David Templeton earlier this year, O’Brien describes the feeling of being in the double bass section of the Philharmonic. “To play the double bass in an orchestra feels like you are in the belly of a submarine,” she says, “with all the machinery going all around you, and everything happening all at once, and millions of notes falling all around you, and having to maintain your steadiness within. We look at each other coming off the stage and say, ‘This is why I became a musician. For this experience.’”

I hope you can watch The Only Girl in the Orchestra. It’s a wonderful documentary. And for fun I leave you with a taste of the virtuosic possibilities of the bass: Bottesini’s Grand Duo for violin and bass with violinist Augustin Hadelich and double bass player Xavier Foley.

Augustin Hadelich & Xavier Foley – rehearsal video of Bottesini Grand Duo Concertant

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter