Flanders & Swann © Flanders and Swann

After almost a lifetime of music-making and trying to figure out what it is saying, I’m coming closer to the thought that the message of music is the music itself.

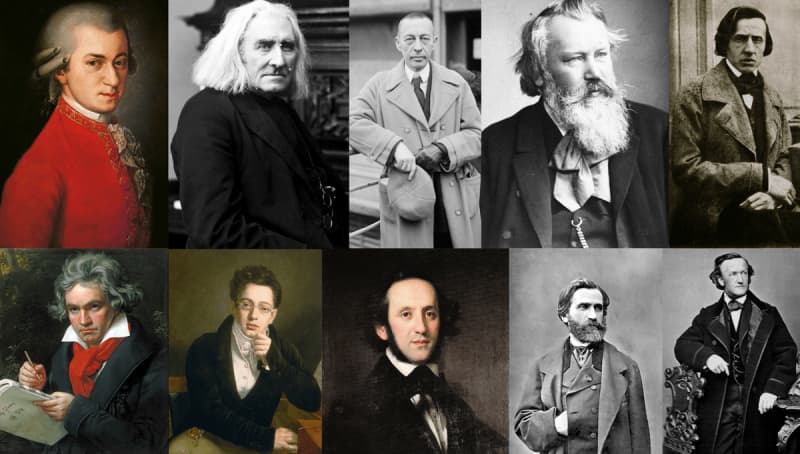

For an experiment in discovery, I’ve been listening to all of Mozart’s Horn Concertos. Wikipedia says that “The four Horn Concertos by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart were written for his friend Joseph Leutgeb whom he had known since childhood”.

My favourite is his fourth, the Horn Concerto E-flat major K. 495. In this quite surreal performance by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, with Marc Gruber on Horn and Elias Grandy conducting, the lack of an audience because of COVID-19 restrictions makes for a scary image of our times.

But why? Why is this horn concerto my favourite? What was and is the message in this music? Is it the highly popular and parodied Rondo movement by Flanders & Swann that makes it my favourite? It is. But the other two movements are equally good, in my opinion.

Maybe Flanders & Swann the British comedy duo who were most active in the 1950s and 1960s were onto something when they added lyrics to Mozart’s Rondo. Maybe the message of music is in its lyricism? But clearly, that can’t be the case when we experience and love so much non-lyrical music.

If you study, you might find that non-lyrical music is best for focusing your attention on your subject. It would seem that lyrical music draws your attention away from your subject because you either know the lyrics or you subconsciously try to add words to highly singable tunes, as Flanders & Swann did. There has been research around “The differentiated effects of lyrical and non-lyrical music on reading comprehension”, but more needs to be done.

I think it was the English composer Gordon Jacob, whose Suite for Recorder and Strings just maybe one of the most gorgeous compositions around, said that “1000 people who listen to a piece of music will have 1000 different experiences”.

This, among many other things and years of fruitless research, are the reasons I now think that the message of music is the music itself. I could convince myself that music has many messages written into its structure, but how do I convince others? I guess that’s not possible. We know that for most people, that even when confronted with facts, we choose to believe what we do regardless of evidence or hard data.

Haydn’s Clock Symphony © BBC

I could explain the messages that I encode into my music, which I do. But would that explain the message of the music to you? Sometimes, I take from other composers and add a bit about what they were saying. Other times, I purposely add emotional triggers into my music to get you to feel something more than what the music is saying. Such as descending thirds, these are quite a simple method to express emotion.

The well-known Lullaby by Brahms has ascending and descending minor thirds. Now, given its title, the music really tells a story, doesn’t it? So, it’s saying something, and something specific. What it is saying is not just in the context of its title though, it is written into the music. But is that only because we know the title and what it’s meant to represent? If you didn’t know the context and heard it for the first time, would you think it is a lullaby?

The words concerto or symphony tell you nothing about the style of music you are about to hear, but a lullaby, as you would guess, it’s not generally going to be about war or anything other than singing a child to sleep. So, the story of some music is in its title. Or in the subtitles that have been ascribed to music, like many of Haydn’s symphonies have been.

Does the second movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 101, really sound like the ticking of a clock? There’s an old saying that goes, ‘call a dog a dog and it becomes a dog’. What that means is title something, and colloquially, it becomes that title and at some time it formally becomes known by that name. It’s the same for music titles or nicknames of music. Radio station announcers will say, “Up next is Haydn’s Clock”, and most listeners will know exactly what they are about to hear.

I believe that we are forced to think that the message of music is the music itself. Because the argument about what music is saying can never be settled, and it can never be proven because we all hear music differently.

It seems a difficult concept, especially today in our highly technical world where everything is researched deeply and must be defined, that accepting something for what it is without applying alternate meanings to it can be a satisfactory explanation. However, if there is something that should stand alone and simply say, listen, I am just music, it is music itself.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter