The American conductor who founded New York’s Young People’s Concerts preceded Leonard Bernstein by two generations

His funeral was attended by all the greatest musical names of his time, including Toscanini, Barbirolli, Heifetz, Menuhin and Mengelberg. High society was represented by Astors, Vanderbilts and a host of others. Yet you’ve probably never heard of Ernest Schelling.

Born in 1876 in Belvidere, New Jersey, Schelling gave his premiere as a pianist at the age of 4 in the Philadelphia Academy of Music. Years later, a friend told the story: “Dressed like a little Mozart, in a red velvet suit with collar and sleeves of lace, he appeared before a large audience. For encouragement, as he went out on the stage, he was given a gold piece. He had a raised stool and a specially constructed pedal. He played the first three sonatinas by Clementi, but in the middle of the ‘Impromptu’ of Heller, his gold piece fell to the floor and rolled toward the footlights. In those days, there was no electricity. The footlights were gas flames. Little Ernest jumped from the stool and ran after his treasure. Stooping to pick it up, his lace sleeves caught fire. The flames were quickly snuffed out by the master of ceremonies, and Ernest, with complete composure, returned to the piano and finished his program.”

Schelling’s childhood consisted of endless practicing and performing for the royalty of Europe. His teachers included the Chopin student Georg Mathias, Isidor Philip, Moritz Moszkowski, Theodor Leschetizky and, from 1898 to 1900, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Schelling toured Europe and the Americas in the years leading up to World War I. Listen to his 1916 Duo-Art recording of the Liszt Sonata, and you’ll hear fantastic tempos with absolute command.

Schelling published one transcription, the Prelude to Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. The sophistication and ingenuity of the writing for the piano make it an ideal partner to Liszt’s famous transcription of the end of Tristan, the Liebestod. For example, Wagner’s orchestra plays the measures below as melody with homophonic chords. Schelling captures its fluid nature with dreamlike arpeggios that alternate between triplets and quadruplets, always improvising their shape.

You can judge the creativity of the transcription in Paderewski’s 1930 recording:

Paderewski plays the Prelude to Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde,

transcribed for piano by Ernest Schelling.

Schelling’s compositions are characterised by similar passagework. Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered his most famous work, A Victory Ball, which was recorded by Willem Mengelberg in New York and frequently performed by John Philip Sousa and his band. His music was also programmed by most of the leading conductors of the day, including Max Fiedler, Felix Mottl, Karl Muck, Arthur Nikisch, Hans Richter and Frederick Stock. His violin concerto was written for Fritz Kreisler and also played by Efrem Zimbalist and Mischa Mischakoff. His music has fallen from favour, though.

All this was the background to the most impactful part of his life. At the age of 48, he picked up the baton for the first time in order to lead a new series for the New York Philharmonic, Young People’s Concerts (YPCs). Schelling wasn’t the first to conduct a youth concert; that distinction went to Carl Barus and the Philharmonic Society of Cincinnati on July 4, 1858. Theodore Thomas, Walter Damrosch, Stokowski and others continued this tradition in a half-dozen American cities, and philanthropist Robert Mayer brought the practice to London.

Schelling’s series was notable for its vitality and scale. From 1924 until his death in 1939, Schelling conducted 295 YPCs with the New York Philharmonic. In addition, he established a series and conducted 179 concerts with 13 other orchestras, including Boston, Cincinnati, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Haven, as well as Utrecht and Rotterdam in Holland. Much as Bernstein broadcast YPCs on CBS Television, Schelling conducted concerts for CBS Radio.

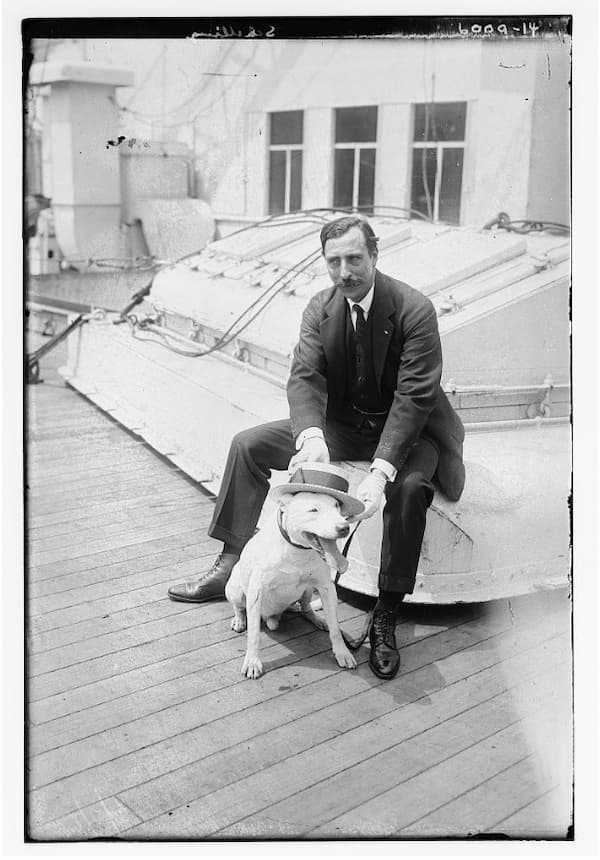

Schelling with his dog, Nicky. Schelling wrote a letter to one

student claiming, “Nicholas can play the piano.” (Library of Congress)

Schelling developed colour slides to accompany his talks from the podium. An entertaining speaker, he could play the piano with his back to the instrument or play a melody with an orange in hand. Programs of 75 to 90 minutes consisted of short pieces, demonstration solos by musicians and an audience sing-along with the orchestra. Following the concert, students filled out questions provided in notebooks. Prizes were awarded at the last concert of each season for the best notebooks.

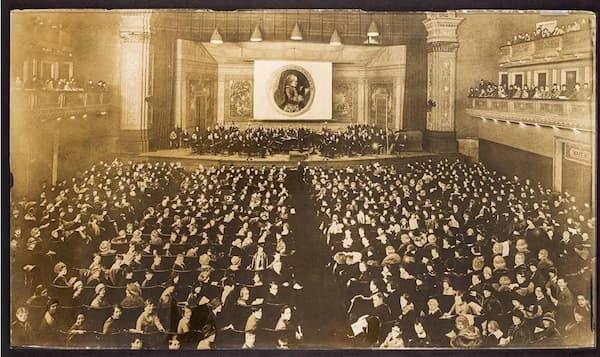

An early Young People’s Concert (from New York Philharmonic archives)

“Uncle Ernest,” as Schelling was called at the concerts, was often recognised on the street by one of the 200,000 students who ultimately attended his programs. Paper airplanes or other disturbances were rare at the concerts. Why was he able to communicate with children so well?

Thomas Hill, the author of a 1970 doctoral dissertation on Schelling, wrote, “In later life, those who knew Ernest Schelling most intimately felt that his affinity for children and the great amount of effort which he put into his concerts for them to the detriment of his career as pianist and composer were partially attributable to his barren childhood. He wanted to be with children and of service to them.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter