Why another book about the Holocaust, you might ask? The effects of World War II, and the experiences of the millions who perished, and the many millions more who were displaced, who became refugees, and who were among those who liberated the concentration camps, have seeped into the genes of subsequent generations. We children of survivors and of liberators have been irrevocably marked—this, despite our parents doing everything they could to shield us from the past. Survivors tended not to share their stories. They wanted to move on, to start anew, to forget. But the next generation has become consumed with trying to understand and learn the truth about our histories.

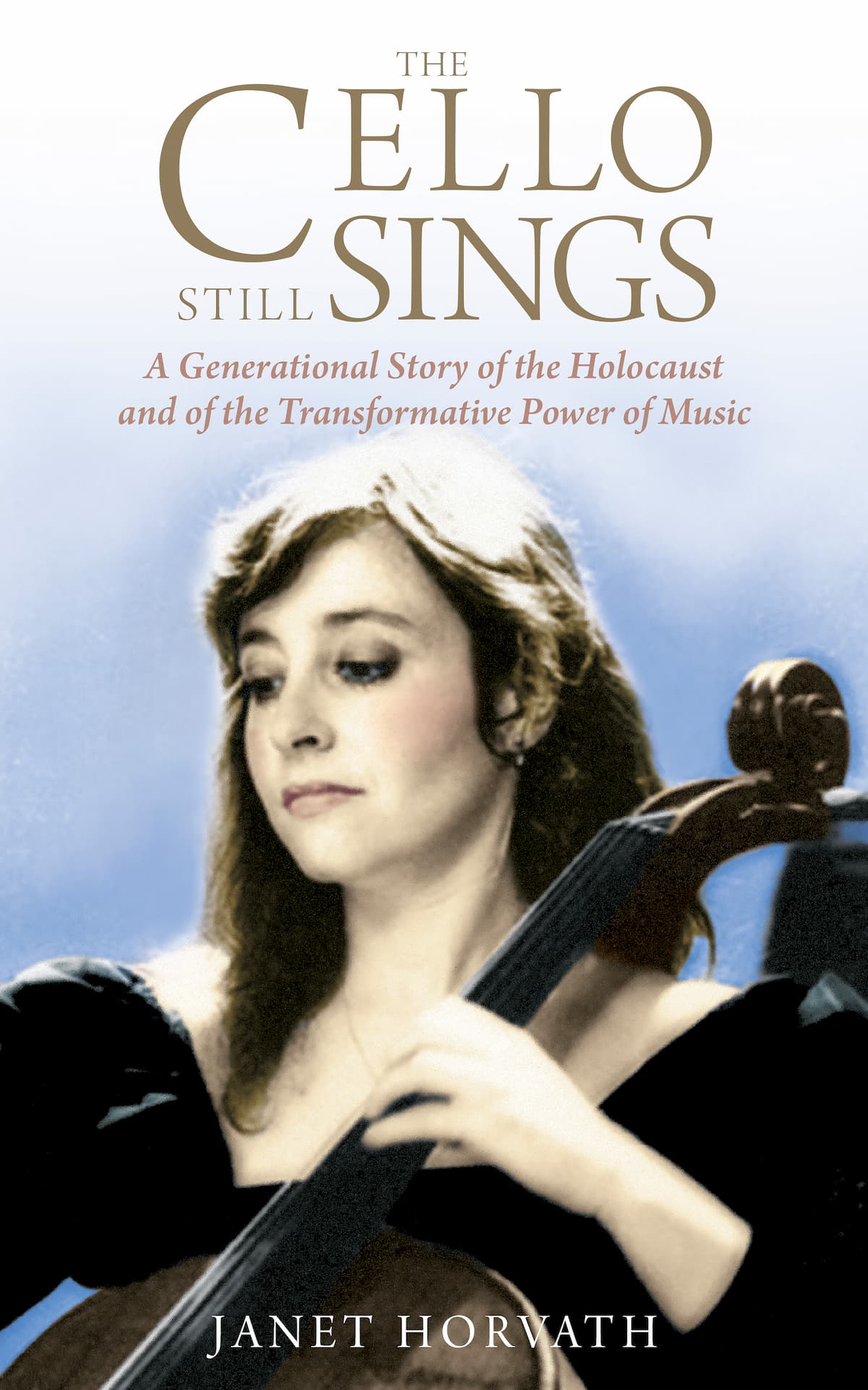

The Cello Still Sings – A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music, by Janet Horvath

Although my parents evaded being shipped to a death camp, unlike 500,000 other Hungarian Jews, my father was rounded up for slave labor and sent to the copper mines of Bor, Yugoslavia. Instead of a cello-bow, he toiled with a pickaxe and shovel and strained to push wheelbarrows filled with rubble. My mother, only seventeen at the time, hid in coal bins, and under lumber and debris, while Budapest was under siege and bombarded late in the war.

As a child, I was haunted by the eerie hush surrounding my parents’ experiences. George and Katherine, two professional musicians, buried the memories of who and what they were before, silencing the past in order to live. Music was their lifeline.

The young George Horvath, father of the author Janet Horvath

After five decades of secrets, I stumbled upon a clue. I asked my father an innocent question about music. He revealed that after the war, he performed 200 morale-boosting concert programs throughout Bavaria from 1946-48 in a twenty-member orchestra of concentration camp survivors. Although I also became a professional cellist, my father had never disclosed that two of the programs, in 1948, were led by the legendary American maestro, Leonard Bernstein. One of them was held in the town of Landsberg, Germany, for 5000 survivors, American military, and observers. When I learned of this performance, I was able to track down the original printed program in the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, and much to my surprise, they had photographs of the event. Finding these artifacts and showing them to my father, galvanized him to write down his testimony for me – in Hungarian. My father finally told me his story just weeks prior to his death.

With details of the places my father was incarcerated and where my father performed after the war, I made a pilgrimage to Europe to learn more and discover how families like mine were able to begin anew.

Janet Horvath performs Max Bruch’s Kol Nidrei

After struggles as immigrants in a new land—cleaning and working in sweatshops—my father was able to land a position with the Toronto Symphony. My mother began her successful piano studio. They spent their lives making music and bringing beauty and joy to others.

The story comes full circle. In 2018, the town of Landsberg, Germany planned a commemorative program upon the 70th anniversary of the performances in 1948 with Leonard Bernstein and his 100th birthday. I was invited to play the cello solo Kol Nidre by composer Max Bruch with an orchestra of German youth. My family and several others whose parents had languished in the DP camp in Landsberg joined the townspeople for what turned out to be an out-of-body and reconciliatory experience—the lingering scars healed through the sustenance and power of music.

Janet Horvath Plays Kol Nidre

Here is an excerpt:

A CONCERT WITH LEONARD BERNSTEIN IN MAY 1948

He’d already called three times that morning. “Janetkém. When you are coming?” With a firm grip on the steering wheel, I slalomed the car forward on black, ice-covered roads toward my father’s high-rise. The dense traffic and the treacherous surfaces hindered my progress. I chose a circuitous route, unplowed but easier to negotiate. With shoulders raised to my ears, I slid into a parking spot and braced myself for the cold trek to the front door. My elevated pulse didn’t surprise me. The dusky sky threatened more sleet, and I was nearly late.

The elevator door opened onto the 14th floor, and there stood my father, clean-shaven, waiting in his camel hair coat and jaunty black chapeau. Underneath, as always for any outing, he was dressed in a suit—the gray pinstriped one with a crisp tailored shirt, multicolored matching silk tie, leather shoes tied just so.

Raising his unruly eyebrows, now speckled with gray, he said with a twinkle in his eyes, “Janetkém, where were you so long?”

Janet Horvath’s parents in Toronto, 1950

We embraced and made our way painstakingly into the elevator.

My father at 87 was still sharp, critical, astute; his old-world European elegance and high standards of behavior were unchanged; his taste in fashion, art, and cuisine uncompromised; and his thick Hungarian accent undiminished. Still, the least slight could set him aflame. He leaned precariously on his walker. When had his posture become so stooped, his physique so frail? He would often forget about his unsteadiness, which had resulted in sudden falls.

As we left the building buffeted in the subzero wind tunnel, I was grateful I hadn’t chosen this location for my parents, because I would never have heard the end of it. My father loved all things beautiful. He selected this building because of the striking gold fixtures in the bathroom and contemporary marble tiled floors. The lobby of the multistory condominium located on Yonge Street, the main north-south corridor of Toronto, exudes refinement with its leather furniture, floor to ceiling mirrors, and luxuriant plants—a monolith above the bustling street. But the steep incline between the parking lot and the entryway is difficult even for young people to negotiate. The first week my parents lived there, my father fell flat on his face, breaking his nose. A superstitious man, he decided the place was cursed.

Leaning into the wind, I tightened my hold on him. We lumbered to the car, then I reminded him to place his behind in first and to lower his head so he wouldn’t bump it on the way in. I bent down to grab his legs and hoisted them into the car. Success. No bruises or breaks this time. Once I had heaved the walker into the trunk, I settled into the driver’s side, sighing audibly in anticipation of the tedious drive to yet another doctor’s appointment, this time the neurologist, for his Parkinson’s disease symptoms.

“Watch how you are driving, Janetkém.”

Still uneasy, I focused on the rugged inflection of his voice, the sound of his fingers tapping on the center console. Cello-playing fingers need to be supple. He was always practicing even without the instrument, even on an armrest, even now that he no longer played. This life-long mannerism temporarily impeded the oscillating tremor in his limbs.

I considered harmless subjects for conversation and settled on music. He loved to talk shop. My orchestra was preparing a festival to honor Leonard Bernstein—the legendary maestro, educator, and pianist, bad boy and superstar—the genius who composed West Side Story; who for nearly half a century conducted the New York Philharmonic.

Despite more than three decades of cello playing, I never crossed paths with Bernstein. But my father, a wonderful cellist in his day, performed under the batons of the greatest conductors as a member of first the Budapest Symphony and then the Toronto Symphony.

He was quite hard of hearing by then, so I hollered, “Papa. Did you ever play with Leonard Bernstein?”

The tapping stopped. His skin paled. He shifted in his seat, rubbed his rheumy eyes, and placed the palm of his hand on his cheek. Several moments passed. Should I pull over? I decided to remain quiet, concentrating on the road, when a whoosh of air escaped from his lungs.

“Yes,” he said. “It was very hot day. He came. To conduct Jewish Orchestra in DP camps. In 1948. After war. He played George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue on piano. He was just a kid and was just fan-tas-tic! ‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘let’s take off our jackets and roll up our sleeves. We are just schvitzing!’” My father laughed. “I talked to him… in German. I said, ‘I want come to America.’ So warm Bernstein was. He said I am great Jewish musician. I should go to Palestine.”

Perspiration oozed down my neck. Resisting the urge to brake, I considered what to do. He’d never told me this story before, or others. Ice pellets strafed the car and my father, a defiantly taciturn man, had just disclosed a long-held secret. Hoping for more, hoping not to intrude, I kept driving.

Janet Horvath The Cello Still Sings

The Cello Still Sings – A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music, published by Amsterdam Publishers tells our family story. The sweeping history is sprinkled with colorful anecdotes about my life and my father’s life in music and moreover is a story of reclaiming life after statelessness.

Available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Indigo Books Canada, Book Depository, and your favorite local bookseller.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

As a daughter of Holacaust survivors I could relate to the parent child relationship-where many times the child is the parent. This book is a very loving respectful picture of a relationship with many challenges but always with love.

I found it hard to put this book down.