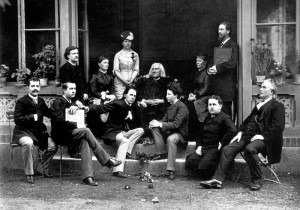

Franz Liszt with his pupils.

1st row: Saul Liebling, Alexander Siloti, Arthur Friedheim, Emil von Sauer, Alfred Reisenauer, Alexander Gottschalg. 2nd row: Moriz Rosenthal, Viktoria Drewing, Alexandrine Paramanoff, Franz Liszt, Annette Hempel-Friedheim (A. Friedheim’s mother), Hugo Mansfeldt

School’s out for summer! Well, formal school, but practicing continues on forever. We know how influential our teachers can be so we thought we’d look at teachers of the past and see how curiously far they reach into the present.

One of the most important pianists of the 19th century was Franz Liszt and he also had a substantial reputation as a teacher. Some pupils described their lessons as masterclasses of 10-20 students where others were in smaller 5-pupil classes that might meet 3 times a week. Students had to perform from memory and would pile their scores at the front of the room. When Liszt found one of interest, he would have the student perform, but if he heard a mistake, the student would be swept off the piano bench and replaced by another. Liszt rarely played privately in these classes and students resorted to various subterfuges to get the maestro at the keyboard to “show them how….”

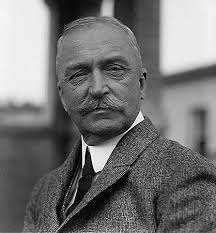

Hans von Bülow

Let’s start with Christoph Willibald von Gluck (1714-1887). One of his students was Antonio Salieri (1750-1825) and one of his students was Franz Liszt (1811-1886). Liszt was the teacher of Hans von Bülow (1830-1894) who taught Walter Damrosch (18622-1950), who is best remembered today as the longtime director of the New York Symphony Orchestra (which later became part of the New York Philharmonic). So in just 5 generations, we go from the early 18th century to the mid-20th century and the creation of the leading American orchestra.

Bach: Chorale Prelude, BWV 720, “Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott” (arr. W. Damrosch) (BBC Symphony Orchestra ; Leonard Slatkin, Conductor)

Following a different line from Franz Liszt, we see the development of music in Russia: Liszt to Alexander Siloti (1863-1945) to Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943).

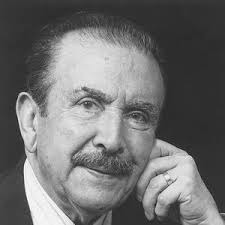

Liszt’s teaching lines can be extended to Malcolm Bilson (b. 1953), who has done so much to promote the reexamination of the pianoforte (which would have been used by Liszt’s teachers) and Claudio Arrau (1903-1991) and his student Garrick Ohlsson (b. 1948).

Claudio Arrau

Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, 3rd year, S163/R10: IV. Les jeux d’eau à la villa d’Este (Garrick Ohlsson, piano)

If we look at the teaching line parallel to Salieri, we can look at Mozart. His pupil Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) taught Carl Czerny (1791-1857), born the year Mozart died, who taught Theodor Leschitizky (1830-1915) who taught Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) to Leon Fleischer (b. 1928). Fleisher’s line also connects back through Czerny to Beethoven, another of Czerny’s teachers.

Alicia de Larrocha

When you look at direct influences, we can look at the Spanish pianist Alicia de Larrocha, for instance. She is a great champion of the work of fellow countryman Enrique Granados, but to understand her authority over his music, you have to follow the trail back from Alicia de Larrocha back to her teacher Frank Marshall back to his teacher Enrique Granados. Granados’ untimely death by German submarine meant that his papers were in disarray so it was left to his students to make the definitive versions of his work. The reason that his work Goyescas is considered a united multi-part work and not 3 separate publications is due to the word of the master passed from student to student.

Granados: Goyescas: No. 5 El amor y la muerte (Love and Death) (Alicia de Larrocha, piano)

As students become teachers, they pass down the influences from their own teachers, who learned in the past from even older teachers. Each generation builds on the next and so music maintains this web of continuity.