Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007) was a very powerful man indeed. During the 1930s, he was hailed as the leading Soviet composer, and by 1948, Khrennikov was nominated as General Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers. That powerful state-created organization for musicians and musicologists was created in 1932 by Joseph Stalin to “contribute to the moral and ethical education of a modern person.” Khrennikov certainly held some strong views, including the notion that “Stalin was a genius and absolutely normal person who knew music better than any of us.” Reading statements like that made us want to learn a bit more about the man and the composer.

Tikhon Khrennikov: 5 Pieces for Piano, Op. 2 (Evgeny Kissin, piano)

Childhood and Studies

Tikhon Khrennikov

The youngest of ten children born into a family of horse traders, Khrennikov quickly displayed great musical potential. He learned to play a number of instruments, sang in local choirs, and played in a local orchestra. He counted Vladimir Agarkov and Anna Vargunina among his most important first teachers, and he started to compose at the age of 13. Khrennikov moved to Moscow in 1929 and studied composition at the Gnesin Academy of Music with Mikahail Gnessin and Yefraim Gelman. By 1932 he was accepted as a second-year student at the Moscow Conservatory. There, he studied in Vissarion Shebalin’s composition class and piano with Heinrich Neuhaus.

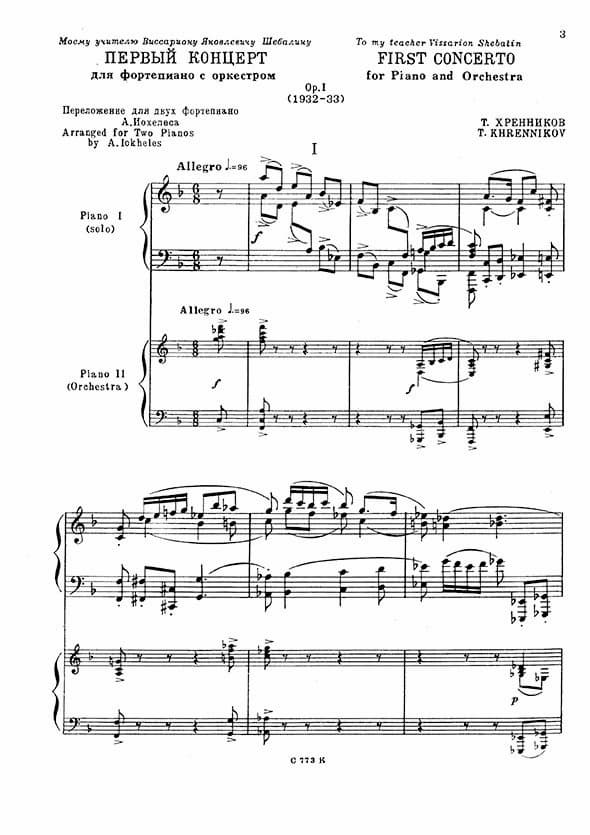

His first piano concerto dates from his student days at the Moscow Conservatory. Khrennikov was an exceptional pianist, and this student exercise was clearly designed to showcase his pianistic skills. Originally scored in three movements, the composer decided to add a fourth, and this new version premiered in 1935. The work is dedicated to his teacher Shebalin, and ironically, Khrennikov would denounce him as a “formalist” a decade later. Khrennikov performed his first piano concerto on a number of occasions, turning him into an instant star on the Soviet music scene.

Khrennikov Performs Khrennikov’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in F Major, Op. 1

Political Opportunities

Khrennikov submitted his First Symphony, Op. 4 as his graduation work in 1936, and he became politically active. Dmitri Shostakovich’s popular opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was being torn apart in the press, and the famous article “Muddle Instead of Music” appeared in the Soviet newspaper Pravda on 28 January 1936. It was rumoured that Joseph Stalin might have been the author, but in the event, it denounced Shostakovich’s opera as “formalist, bourgeois, coarse, and vulgar.” In due course, this particular article became one of the most frequently cited examples of Soviet censorship of the arts.

Tikhon Khrennikov

Khrennikov, sensing his opportunity, became part of the discussion. He wrote, “We developed an enthusiasm for modern western composers. The names of Hindemith and Krenek came to be symbols of advanced modern artists. After the enthusiasm for western tendencies came an attraction to simplicity, influenced by composing for the theatre, where simple, expressive music was required. We grew, our consciousness also grew, as well as the aspiration to be genuine Soviet composers, representatives of our epoch. Compositions by Hindemith satisfied us no more.”

Tikhon Khrennikov: Symphony No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 4

Musical Optimism

And Khrennikov continued, “Prokofiev arrived, declaring Soviet music to be provincial and naming Shostakovich as the most up-to-date composer. Young composers were confused: on the one hand, they wanted to create simpler music that would be easier for the masses to understand; on the other hand, they were confronted with the statements of such musical authorities as Prokofiev…Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk contains several large melodic fragments which opened some creative perspectives to us. But the entre‘actes and other things aroused complete hostility.”

Khrennikov, together with Khachaturian, Boris Shekhter and others, became signatories to an official statement welcoming “a sentence of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union, passed on traitors against the motherland and fascist hirelings,” which led to the trial and execution of countless individuals. On the musical front, Khrennikov developed a characteristic style that he would maintain over the next 60 years. A musicologist writes, “Khrennikov adopted the optimistic, dramatic and unabashedly lyrical style favored by Soviet leaders, and his attraction to popular theatrical genres did not change.”

Tikhon Khrennikov: Much Ado about Nothing, “Serenade of Borahio” (Moscow Chamber Opera Theater Orchestra; Anatoly Levin, cond.)

Music in praise of Stalin

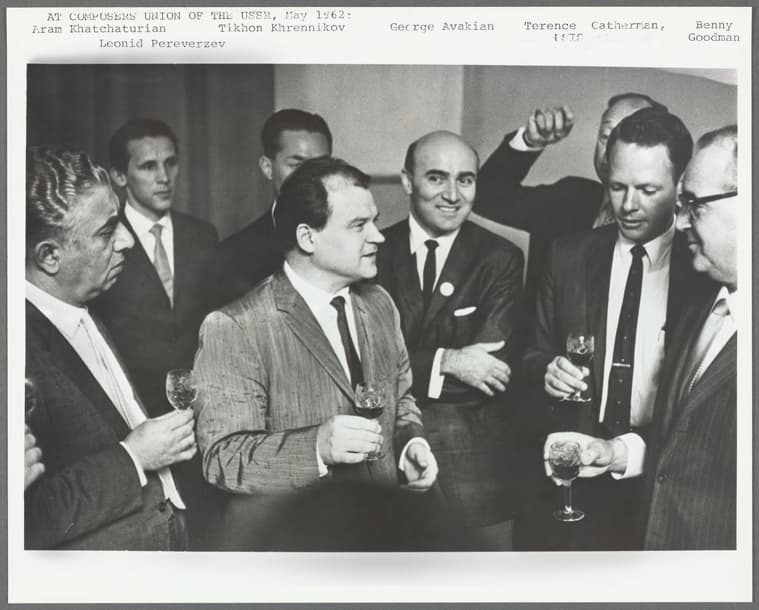

The Composers Union, 1962

The naïve optimism reflected in Khrennikov’s music was quickly noticed and supported by Stalin and the Party officials headed by Andrei Zhdanov, the Secretary of the Central Committee. In addition, Dmitri Shepilov, deputy chief of the department of agitation and propaganda, saw in Khrennikov’s music the opportunity to create enthusiasm for socialism in Soviet culture. Composing the music score for the popular Soviet film “They Met in Moscow” of 1941 propelled Khrennikov to national fame. He was also awarded the Stalin Prize and rewarded with the position of Music Director of the Central Theatre of the Red Army.

Tikhon Khrennikov: “Lights of Moscow” (Matti Salminen, bass; Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra; Riku Niemi, cond.)

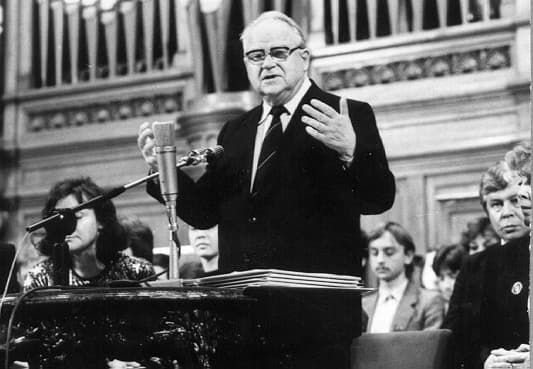

General Secretary

On 10 January 1948, the Kremlin summoned 70 composers, musicians, and music lecturers to a three-day conference. The chief ideologist of the communist party Andrei Zhdanov lectured everybody on how to write music in praise of the Socialist State. Khrennikov was one of the main speakers, and he ruthlessly attacked all three of the greatest composers present: Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Khachaturian. As it all too frequently happens in totalitarian circles, he later defended himself by stating, “They told me, they forced me, to read out that speech attacking Shostakovich and Prokofiev. What else could I have done? If I had refused, it would have been curtains for me.” Stalin was certainly impressed and appointed Khrennikov General Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948, a position he would keep until the union was disbanded with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Tikhon Khrennikov: Symphony No. 2, Op. 9 (USSR State Academic Symphony Orchestra; Evgeny Svetlanov, cond.)

Shostakovich and Tikhon Khrennikov

It would far exceed the scope of this article to detail Khrennikov’s activities on behalf of Soviet leadership, but countless intellectuals, musicians, composers, and scholars suffered greatly under his doctrine. Sometimes, Khrennikov could be helpful, just as long as it was not dangerous for his own position and career. In his instrumental music, Khrennikov was initially influenced by Shebalin and Hindemith, and later by Prokofiev. His mature style remained deeply traditional, and “his tendency towards a popular musical language and towards melody played an important part in his operas. Arias and monologues are quite often replaced by songs written in everyday folk style.” His comic operas have much in common with the operetta, and feature sentimental waltzes and other standard dance and song forms.

Tikhon Khrennikov: Into the Storm, Op. 8 (excerpts) (Daniil Shtoda, tenor; Russian Philharmonia; Constantine Orbelian, cond.)

Return of the Virtuoso

Khrennikov returned to the concert platform during the 1960s and frequently appeared as soloist in his three piano concertos. A critic writes, “as soloist, he was highly successful in putting across the infectious emotion, the salient turns of phrase, and the energetic motion of the music.” His natural musicality and his delight in virtuosity were infectious, and Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich commissioned concertos for violin and cello, respectively. Khrennikov added a second cello concerto in 1985 and a fourth piano concerto in 1991. His Third Symphony attempted to invoke a more sophisticated musical language, but he was never at ease with serialism, “which he denounced vociferously in earlier years.” Khrennikov was far more comfortable with bold and optimistic musical statements.

Tikhon Khrennikov: Violin Concerto No. 2 in C Major, Op. 23 (Igor Oistrakh, violin; Spanish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra; Vladimir Fedoseyev, cond.)

Tikhon Khrennikov’s Piano Concerto No. 1 for two pianos

During his final years, Khrennikov publicly stated his disapproval of Perestroika, its leaders, and the fall of the Soviet Union. As he wrote, “It was a betrayal by our leaders. I consider Gorbachev and his henchmen, who deliberately organised persecution of Soviet art, to be traitors to the party and the people… As in classical Ancient Greece, so too in the Soviet Union music was of the greatest importance to the state. The spiritual influence of the greatest composers and artists in the formation of intelligent and strong-willed people, first of all through radio, was enormous.” Khrennikov died in Moscow at the age of 94 and was happiest, according to his memoirs, when sitting over a sheet of music paper or at the keyboard.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter