Gerard van Honthorst: The Concert (1623)

(Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

In the Renaissance, the musical score didn’t exist. Each singer received their own part book and sang from it. In this 17th century painting, we see the singers and players gathered around the table, each with a separate book in front of them.

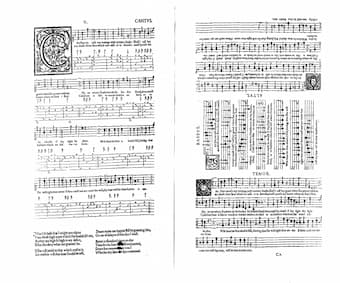

John Dowland’s Book of Songs (1597) was published with all 4 parts spread across two pages, designed to be placed on a square table, with one singer per side. It could also be performed just with one singer and lute.

John Dowland: Book of Songs, Book 1 – Can she excuse my wrongs (Ruby Hughes, soprano; Reinoud van Mechelen, tenor; Paul Agnew, tenor; Alain Buet, bass; Thomas Dunford, lute)

John Dowland: Can she excuse my wrongs with vertues cloake (Rogers Covey-Crump, tenor; Jakob Lindberg, lute)

Dowland’s Can Shee Excuse my Wrongs

An extension of the part-book idea has been found in a two sets of knives from the sixteenth century that have music engraved on the blades, one knife per voice part. The knife blades for these specialized knives carry music notation on each side of the blade. They seem to date from the mid-16th century, if not a bit earlier, and are thought to have been made in France for an Italian client. Neither the name of the maker or the client is known.

Around the world, once all the individual knives are assembled, there appear to be 2 separate sets. The seven knives at the Musée national de la Renaissance in Écouen, France, have two different kinds of handles, one in ivory and the other in a dark material. A set in London at the Victoria and Albert Museum also has white handles, as so the three knives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Other knives are known to be in The Netherlands, Austria, Belgium and Germany, for a total of 20 pieces.

Both sides of one 16th-century knife. (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

The knives don’t seem to have been designed for use at the table as a piece of silverware. The knives have broad flat blades and a pointed tip. They are more similar to serving knives than table knives. The knife itself is unbalanced and would be hard to use except as a serving tool. It may be, however, that they were only intended to be used as interesting musical artefacts. The knife is larger than you imagine, being nearly 30 cm (12 inches) long.

Each knife contains two musical works, one on each side of the blade. If you look at the example above, when the knife is held in the left hand with the blade down, the music is that for a pre-dinner benediction: Benedictio mense: Quae sumpturi sumus benedicat trinius et unus (Blessing: May the Trinity bless that which we are about to eat)’. When the knife is held with the blade up, the music is for a post-meal grace: Gratiarum actio: Pro tuis deus beneficiis gratias adimus tibi.’ (Thanksgiving: We give Thanks to you, God, for your generosity). On the knives in Écouen, two words in this blessing are reversed: Pro tuis beneficus deus gratias adimus tibi.

The 7 knives at the Musée national de la Renaissance

The 7 knives in the Musée national de la Renaissance collection have differences between then. One set, 4 knives with ivory handles, have the addition of an “Amen’ at the end of the Grace on 3 of the knives. The other set, 3 knives with dark handles, for Countertenor, Tenor and Bassus, do not have the ‘Amen’ ending of the Grace.

The music is on a five-line staff, with a clef, a time signature (cut-C), and the key (one flat). Each song lasts about 30 seconds. The music is unique to these knives. A more typical ‘Benedictio mensae’ is something like this from the Polish Renaissance composer Wacław z Szamotuł.

Wacław z Szamotuł: Benedictio mensae (The Cracow Singers; Marc Lewon, lute; Agnieszka Budzińska-Bennett, cond.)

Notation knives at the V&A

When the question of how these would be used is addressed, one research pointed out that a diner at a Renaissance meal would have his own server who would cutup his food for him. It would have been the servers who had these knives, not the diners.

Recordings of the music of the knives can be heard here.

A modern maker has created his own replicas of the knives in the Victoria and Albert collection.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter