For American composer George Antheil, the mechanisms of the modern age were the future of the world. He thought that ‘The environment of the machine has already become a spiritual thing…’ and wrote music that tried to capture both the mechanism and modern life.

George Antheil

Antheil’s second piano sonata has the title Airplane Sonata and opens with the tempo designation of ‘To be played as fast as possible’ before launching off into ‘unyielding pounding ostinato fragments’.

Written in 1922, the work was described by Erik Satie as ‘precision music’, yet at the same time, the pounding rhythms of the first movement have a hint of ragtime in them. They bring out Antheil’s collage techniques with the shrill and incessant harmonies, clusters, all done at a fortissimo dynamic. However, the work does start with a rather nice uplift to the skies.

George Antheil: Airplane Sonata, “Piano Sonata No. 2” – I. As Fast as Possible (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

Once in the air, the music comes to its slow movement. It’s calmer but still dissonant as our plane and pilot find their place in the sky. A swinging melody over a static bass sweeps us away for a while until we get lost in the clouds in a very impressionistic final section.

George Antheil: Airplane Sonata, “Piano Sonata No. 2” – II. Andante moderato (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

Antheil’s musical blocks in the first movement are part of his ‘time-space’ components – the work is organised around a repeated E which isn’t a functional tonality but rather like Duchamp’s objet trouvé pieces made of repurposed ready-made material, such as his fountain/urinal or his bicycle wheel. Duchamp’s Readymades (as he called them) were items selected, signed, and designated as works of art.

Marcel Duchamp: Roue de Bicyclette (Bicycle Wheel), 1913 (Jerusalem: Israel Museum)

Antheil’s E (or Duchamp’s bicycle wheel) exist in their own time. Many of the techniques used by Antheil would be picked up again by later composers but in a very different context. One example is the ‘two interlocking but independent ostinato patterns a minor second apart that start together but gradually go out of phase’, a technique that will surface again in Ligeti’s minimalism and in the music of Steve Reich.

Antheil embraces the new technologies and takes us through terror to an appreciation of what they represent in terms of progress.

Written in 1922, the work marks Antheil’s introduction to Europe. His London debut was at Wigmore Hall on 22 June 1922, and from there, he moved to Berlin. Post-War Berlin was an increasingly important centre: it was the third largest city in the world and led innovation in science, the humanities, art, music, film, architecture, and other fields. Antheil, with support from his patron Mary Louise Curtis Bok and the income from his concerts, had money to burn. He collected art (“One day I bought myself a whole stack of modern paintings—these consists of two Marcoussis, one Braque, one Picasso, three Dugerts, two Bobermans, two Kubins, one Leger.”) and became a patron of the arts, supporting three young painters he thought had potential. Ballet managers came to see him to get performances in the US, and so on. His 1923 was spent in concerts in Munich, Dresden, Leipzig, Frankfort, and other ‘critical cities’ (his words).

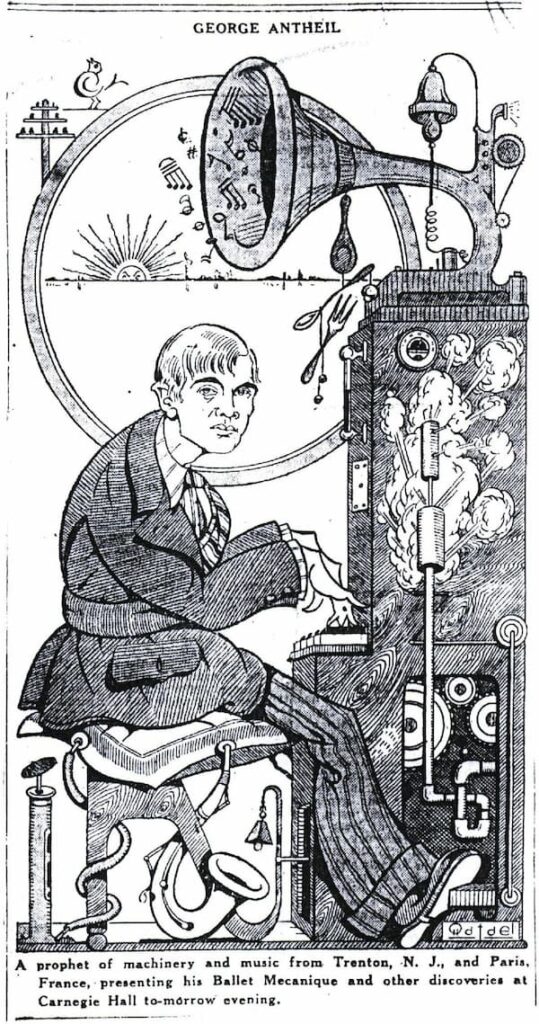

Antheil’s attempts to bring the machine into music ultimately failed, particularly after the disastrous 1927 Carnegie Hall concert of his Ballet méchanique. Even the promotional cartoon for the concert seemed a bit wary of his music.

George Antheil “A prophet of machinery and music from Tenton, N.J., and Paris, France presenting his Ballet Mechanique and other discoveries at Carnegie Hall Tomorrow, 9 April 19287 (New York Sun)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter