César Franck had a rather ambitious and overbearing father! Determined to make the most profitable use of his son’s musical talents, he forced him into a career as a virtuoso pianist. Studies at the Liège and Paris Conservatory set the stage for appearances on the concert platform. Regrettably, César failed to make an impression either by his compositions or his appearances as a performer. Nicolas-Joseph Franck was outraged and suspected that a woman was behind his son’s musical failings. And when he found a composition dedicated to a certain “”Mlle. F. Desmousseaux, in pleasant memories,” he summoned his son and tore the composition into pieces. The dedication referred to Eugénie-Félicité-Caroline Saillot, daughter of a theatrical family who were members of the Comédie-Française Company under the stage name of Desmousseaux. César met Félicité during his Conservatory days, and gave her piano lessons and taught her harmony and counterpoint. But even more importantly, the Desmousseaux household became a refuge from his overbearing father.

César Franck had a rather ambitious and overbearing father! Determined to make the most profitable use of his son’s musical talents, he forced him into a career as a virtuoso pianist. Studies at the Liège and Paris Conservatory set the stage for appearances on the concert platform. Regrettably, César failed to make an impression either by his compositions or his appearances as a performer. Nicolas-Joseph Franck was outraged and suspected that a woman was behind his son’s musical failings. And when he found a composition dedicated to a certain “”Mlle. F. Desmousseaux, in pleasant memories,” he summoned his son and tore the composition into pieces. The dedication referred to Eugénie-Félicité-Caroline Saillot, daughter of a theatrical family who were members of the Comédie-Française Company under the stage name of Desmousseaux. César met Félicité during his Conservatory days, and gave her piano lessons and taught her harmony and counterpoint. But even more importantly, the Desmousseaux household became a refuge from his overbearing father.

César Franck: L’ange et l’enfant

Apparently, Félicité’s keyboard skills often irritated Franck. A cousin observed “Félicité was stricken with true despair at the least mistake during her lessons or when he impatiently tapped his foot, a frequent habit of his. So much so that there were hardly any lessons without tears and that Desmousseaux called her my daughter, the lachrymose Naiad.” Franck might have been highly irritated at Félicité’s playing, but she soon became the chief object of his romantic attention. In 1846 he composed the song L’Ange et L’Enfant to words by the poet and banker Jean Reboul. Vincent d’Indy later described the song, as “a guardian angel of the Catholic religion, and a piece, which rejects the aid of any strange chord and even of any modulation, is really a little masterwork.” As you might have guessed, this was in fact the composition bearing the dedication to Félicité that was so unceremoniously torn to pieces by César’s father. On this Sunday in July 1846, César walked out of his parent’s house for the last time and was welcomed with open arms at the Desmousseaux’s. He wrote the song out from memory again, and presented the new copy to Félicité.

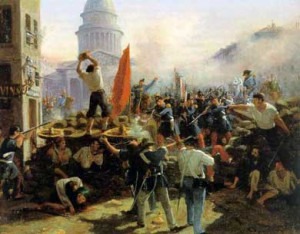

On the occasion of César’s 25th birthday, he informed his father that he was going to marry Félicité. Nicolas-Joseph was beyond words, but the date for the wedding was set for 22 February 1848 at Notre-Dame-de Lorette. However, the guns of the revolution began to fire that very day, and the government of Louis-Philippe descended into chaos. A large number of workers and students marched from the Panthéon to the Madeleine while singing La Marseillaise and throwing stones at the police. Barricades were set up in all the major thoroughfares, and the bridal procession was forced to clamper over the obstacles. D’Indy reports “the revolutionaries willingly helped the couple to make their way over these improvised fortifications.” Once the couple made it to the church another nasty surprise was waiting for them. Nicolas-Joseph, on the insistence of his wife, had grudgingly consented to attend the happy occasion. It is hard to imagine a more trying start to married life! However, their union was a happy one. Except when Franck fell in love with his organ and composition student Augusta Holmès, who “aroused in him the most unspiritual desires.” But that was already the topic of an earlier article!

You May Also Like

-

César Franck “I dared much, but the next time, I will dare even more”

César Franck “I dared much, but the next time, I will dare even more” -

Père Franck In 1843, César Franck began work on his first non-chamber work, the oratorio Ruth.

Père Franck In 1843, César Franck began work on his first non-chamber work, the oratorio Ruth. -

Let’s be Franck! César Franck’s reputation primarily rests on a few large-scale orchestral and instrumental works of his later years.

Let’s be Franck! César Franck’s reputation primarily rests on a few large-scale orchestral and instrumental works of his later years. - Quintet of Discontent

César Franck and Augusta Holmès Find out why Franck received public condemnation from his wife and even Camille Saint-Saëns

More Love

-

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music? - Louis Spohr and Dorette Scheidler

Magic for Violin and Harp "Shall we thus play together for life?"

Although criticized in his own lifetime by other french composers I find his organ music very satisfying. A deeply religious man, his music overtly or covertly contains much Godly material.