Berlioz

Berlioz : Symphonie Fantastique

One of the first, and possibly the most famous and popular, is Hector Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique. According to Leonard Bernstein, this work is the first “psychedelic” symphony, fifty years before the Beatles and only three years after the death of Beethoven. Berlioz was possessed by the idea, which Beethoven inspired, that instead of fitting music into a pre-existing form he could invent his own. Each of the five movements of Symphonie Fantastique takes the listener on Berlioz’ journey—hallucinogenic, dream-like and shaped by his hopeless love obsession, even a drug-induced state!

From the beginning, particular melodies and instruments represent different characters in the work, for example, in the opening movement the violins and flute represent the Idée fixe—the artists’ fixation with the woman whose love he is determined to win. He goes to a ball to win her favor. He paints an idyllic country scene complete with cowbells. Then the work heats up. Berlioz wrote, “The Artist, knowing beyond all doubt that his love is not returned, poisons himself with opium. The narcotic plunges him into sleep, accompanied by the most horrible visions.”

Bernstein’s Symphony no 2 “ The Age of Anxiety”

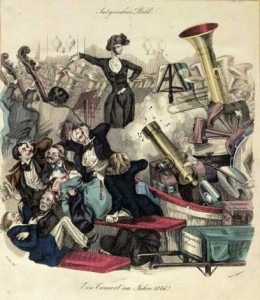

In the final movement, The Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath, we are thrust into a satanic scene. Sorcerers carouse during the Artists’ funeral. Berlioz includes a funeral chant, Dies Irae, in the bassoons and tuba, and visions of hell and damnation in a demonic dance. The work closes in turmoil—mayhem that audiences had never heard before.

Other composers veered away from traditional forms using themes such as Strauss, (Don Juan, Ein Heldenleben) Ravel, (Pavane for a Dead Princess) Liszt, (Totentanz) and Mussorgsky, (Pictures at an Exhibition.)

Later, following in the footsteps of Berlioz, music not only told a story but indicated passions and inner turmoil. Ernst Bloch’s Schelomo: Rhapsody for Violoncello and Large Orchestra, in one sweeping movement and inspired by an excerpt from Ecclesiastes, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity”, and Bernstein’s Symphony No. 2 Age of Anxiety come to mind.

Bernstein: Symphony no 2 “ The Age of Anxiety”

Mahler’s Symphony in D major

Composers still wrote symphonies—Mahler springs to mind, although his symphonies are towering structures, exceeding one hour in length, which require colossal forces including voices, choruses and additional instruments. Mahler believed that, “The symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.” And indeed his music is full of rapidly changing moods, which illustrate all the struggles we encounter in life—suffering, despair, discord, yearning, triumph—incorporating every sound to do so—nature sounds like birdcalls and cowbells, bugle fanfares, banal simple street dances, and soaring melodies.

Mahler’s first symphony has a nickname. Mahler described the work as a Symphonic Poem for the premiere; “Titan” a Tone Poem in Symphonic Form for the second performance, and finally as a Symphony with the additional title of “Titan” for the third performance. By the fourth performance Mahler decided to do away with all program notes and titles. The work became Symphony in D major but the name Titan stuck.

Mahler: Symphony no 2 “Resurrection”

Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 goes by the name The Resurrection. It was the first major work that depicted Mahler’s view of the splendor of afterlife and resurrection. Conceived as a single movement work, the opening movement, completed in 1888 as “Totenfeier” (“Funeral Rites”), originally was a blustery symphonic poem. At the funeral of Mahler’s mentor, Hans von Bulow, Mahler came upon the inspiration for the last movement and the title Resurrection. A children’s choir had performed Friedrich Klopstock’s Aufersteh’n (“Resurrection Ode”), and “it flashed on me like lightning and everything became plain and clear in my mind.” It was Mahler’s favorite symphony and is indeed one of the most popular of his symphonies even today. The last movement is breathtaking.

The Symphony No. 8 “Symphony of a Thousand,” is aptly named. It is the largest scale orchestral work in the repertoire with a huge chorus and massive forces. Mahler though, did not name the work. To be honest the number of performers is greatly expanded but one thousand performers cannot typically fit on a stage. Despite the popularity of Mahler’s Symphonies and the Symphonie Fantastique today, both composers were made fun of. Some audiences thought their music was outrageous.

Although programmatic music persists, many composers have continued to write in the symphonic form, some titled and some not, including Anton Bruckner, Jean Sibelius, Vaughn Williams, Sir Edward Elgar, and today’s composers such as Phillip Glass, Arvo Pärt, Krysztof Penderecki and Henryk Górecki.

People enjoy art that tells a story or which takes you on a journey—one that you have never embarked on before. Like architecture, painting and literature, music has evolved to reflect life’s current complexities.

educational