Dmitri Klebanov

Another prodigiously talented composer is being resurrected from obscurity. Dmitri Klebanov (1907-1987) had two strikes against him during the Soviet era of cultural suppression. He was Ukrainian and Jewish, and his music has been largely unknown. Somehow, he evaded capture, dodged being sent to a forced labor camp, and escaped being murdered like so many other artists were. Much of Klebanov’s music adhered to the dictates of the regime—works that glorified the Soviet Union. But his chamber music reveals another world.

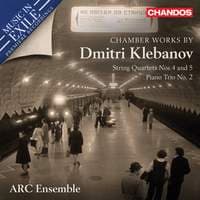

Fortunately, and very recently, the Artists of the Royal Conservatory, the ARC ensemble, which hails from Toronto, Canada, released an album of “Chamber Works by Dmitri Klebanov” the world premiere recording and the fifth in their “Music in Exile” series. The group focuses on the effects that tyrannical regimes, racism, dislocation, and war often have on music, the arts, and creativity.

A composer, violinist, pianist, and conductor, Dmitri Klebanov attended the Kharkiv Institute of Music and Drama and showed remarkable aptitude at a very young age. His earliest works, lost in World War II, include string quartets, a trio, songs, and instrumental pieces. After graduation Klebanov joined the Leningrad Opera Orchestra, playing viola. His year with them gave him the opportunity to play under such esteemed maestros as Bruno Walter, Erich Kleiber, and Otto Klemperer. Once he returned to Kharkiv, he and other Ukrainian artists suffered harsh restrictions due to Stalinist repression. It is not well-known that from 1936 millions of people were rounded up from along the Soviet Union’s western borders and forcibly sent thousands of miles away into eastern and central Siberia. In 1941 Klebanov and 150,000 other Jewish people were apprehended by Nazi invaders and deported to Uzbekistan.

A composer, violinist, pianist, and conductor, Dmitri Klebanov attended the Kharkiv Institute of Music and Drama and showed remarkable aptitude at a very young age. His earliest works, lost in World War II, include string quartets, a trio, songs, and instrumental pieces. After graduation Klebanov joined the Leningrad Opera Orchestra, playing viola. His year with them gave him the opportunity to play under such esteemed maestros as Bruno Walter, Erich Kleiber, and Otto Klemperer. Once he returned to Kharkiv, he and other Ukrainian artists suffered harsh restrictions due to Stalinist repression. It is not well-known that from 1936 millions of people were rounded up from along the Soviet Union’s western borders and forcibly sent thousands of miles away into eastern and central Siberia. In 1941 Klebanov and 150,000 other Jewish people were apprehended by Nazi invaders and deported to Uzbekistan.

Once the war concluded, despite the virtual destruction of his country, Klebanov returned to Ukraine. The Nazi massacre of 34,000 Jews at Babi Yar, a ravine near Kyviv in September of 1941, prompted Klebanov to write and dedicate his First Symphony “To the memory of the martyrs of Babi Yar.” Klebanov, accused of choosing to commemorate Jewish casualties over the Soviet casualties, was stripped of his positions with the leading music institutions of Ukraine, his symphony was denounced and banned, and his music was all but forgotten. Klebanov’s career, destroyed by Joseph Stalin and his henchmen, led to the relative obscurity of his music until well after his death.

Mykola Leontovych

Forced to write within the dictates of the regime, that is, to base compositions on folk melodies and idioms, his early works are accessible and romantic. In his later years Klebanov explores deeper emotions, tragic undercurrents, and hints of dissonance in his chamber music.

The brief but powerful String Quartet No. 4 from 1946 will surprise you. It opens with what we know as the familiar Christmas tune “Carol of the Bells.” But it is a piece by Mykola Leontovych transformed by robust bow strokes becoming almost sardonic. Near the end the composer inserts as exquisite easing of the tempo.

Dmitri Klebanov: String Quartet No. 4 – Allegro

The second movement, typically a slow movement, does begin Larghetto with short solo statements from each string member. But it morphs first into a march, then to poignant solo cadenzas, played at liberty in the viola, then in the violin with a low droning open string. A folk-like, tuneful, and optimistic moderato is followed by an animato-agitato (animated and agitated) a piu mosso (increase in tempo) and finally, completing the movement, a declamatory allargando. For a slow movement of a mere five minutes it’s unusual to transform so often in mood.

Dmitri Klebanov: String Quartet No. 4 – II. Larghetto. Mesto. Marciale – Cadenza tempo rubato poco a poco più mosso – Moderato. Animato – Agitato poco a poco più mosso – Più mosso – Allargando (ARC Ensemble)

The duda bagpipe

The pizzicato scherzo movement of the string quartet is full of energy and humor and not since Ravel have we heard a movement where pizzicato takes the lead. But it is interrupted by sumptuous and lovely bowed melodies. The movement imitates the sound of the Hungarian Bagpipe called the duda—an ancient instrument originating in the 16th century. It has a characteristic sound and produces three notes at the same time, two through a double pipe and the other through a drone. Listen for the viola, which replicates this instrument. The entire quartet is dedicated to Leontovych, who was murdered in 1921 by the Soviet secret police due to his staunch Ukrainian Nationalism.

Dmitri Klebanov: Piano Trio No. 2 – I. Allegro moderato – Agitato – Poco più mosso – Più mosso – Tempo I – Agitato (ARC Ensemble)

Piano Trio No. 2 opens mysteriously with more contemporary harmonies and urgency. The movement hints at a more personal style and deep sentiments. The lovely expansive movement segues into moments of gripping drama especially the deep-throated cello declaration as the movement concludes. The scherzo movement of the trio has its share of pizzicato but hang on to your hats as this movement emphasizes cross rhythms and irregular pulses, which keep the listener and players on their toes.

Dmitri Klebanov: Piano Trio No. 2 – II. Scherzo – Meno mosso – Quasi Valse – Tempo I

Quartet No. 5 is from another world. The last movement is notable. It’s a spirited vivace with tremolo, powerful unisons, and more harmonic and rhythmic variation than the earlier works. Some sections one can’t help thinking of Shostakovich. The fast vivace is interrupted by an otherworldly and haunting chorale-like section before the vivace returns with even more intensity.

Dmitri Klebanov: String Quartet No. 5 – III. Vivace – Andante – Tempo I (ARC Ensemble)

Rather than give away more, I suggest hearing for yourself. This is an album worth owning.

Klebanov, despite the repression, wrote a large number of works including operas, ballets, two violin concertos and two cello concertos, six string quartets, a woodwind quartet, songs, film music, and nine symphonies. Let’s hope that some of this music is soon recorded.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Very nice, but highly derivative music that benefits greatly from a superb performance

The fourth movement is definitely adapts the character of Ukrainian dance called “Gopak”.