While some composers are famous for having previous non-musical careers — the most recent and famous example being Glass, who has been amongst others, a taxi driver, a mover and a plumber. However in many of these cases, the primary reason for such an activity is financial — and temporary, until music satisfies all needs. In some cases it is different, and rather than financial, the main motivation for a parallel career is artistic; a necessary step for the development of the musician’s creativity. Here are two composers whose works have been hugely influential, and who owe much of their originality in that for some part of their life, they have worked in a different art field.

John Cage © pyxis.nymag.com

John Cage is known for having turned the musical world upside down; in a recent interview, the Iranian harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani called him “the big elephant in the room” when it comes to modern music. He is known for having pioneered indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, non-standard use of musical instruments and graphic notation, and the inclusion of Eastern philosophies in Western music.

Before studying with Cowell and Schoenberg — two major figures of modern innovations in music — Cage wanted to be a writer. That led him to travelling to Europe for over a year and studying art under many of its forms: architecture, painting, poetry and finally music.

White Painting by Robert Rauschenberg that inspired John Cage’s 4’33”

© uk.phaidon.com

This would of course influence his works, from 4’33 that takes inspiration in the paintings of Robert Rauschenberg, to discovering the philosophy of the I-ching and chance-controlled events in “Music of Changes”, the development of modern dance through his relationship with Merce Cunningham, and music notations that resemble architectural blueprints.

When it comes to the influence of architecture on music though, it is better explained with Xenakis.

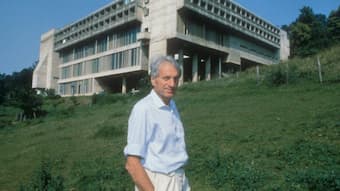

Iannis Xenakis © www.bbc.co.uk

Iannis Xenakis is as much an architect than a composer. He was fortunate enough to study and work with two major figures of architecture and music: Le Corbusier and Messiaen. The latter once told him: “You have the good fortune of being Greek, of being an architect and having studied special mathematics. Take advantage of these things. Do them in your music.”

Philips Pavillion © Louis Warzée, 1958

Indeed, with a degree in engineering, Xenakis moved to Paris and designed with Le Corbusier some of francophile Europe’s most important buildings. His architectural participation includes Brussel’s unique Philips Pavilion.

He then decided to leave the world of architecture and apply his experience to music. This led him, of course, to revolutionise the music of the 20th century: through complex musical forms, alternate graphic notation, and architectural, mathematical and physical principles. In Metastasis, Xenakis introduced independent parts for every musician of the orchestra and in Pithoprakta the note distribution is done through statistics!

Both Cage and Xenakis’ former careers forged their perception of art and the unique shaping of their music. It seems that the best way to think out of the box is to spend some time out of it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter