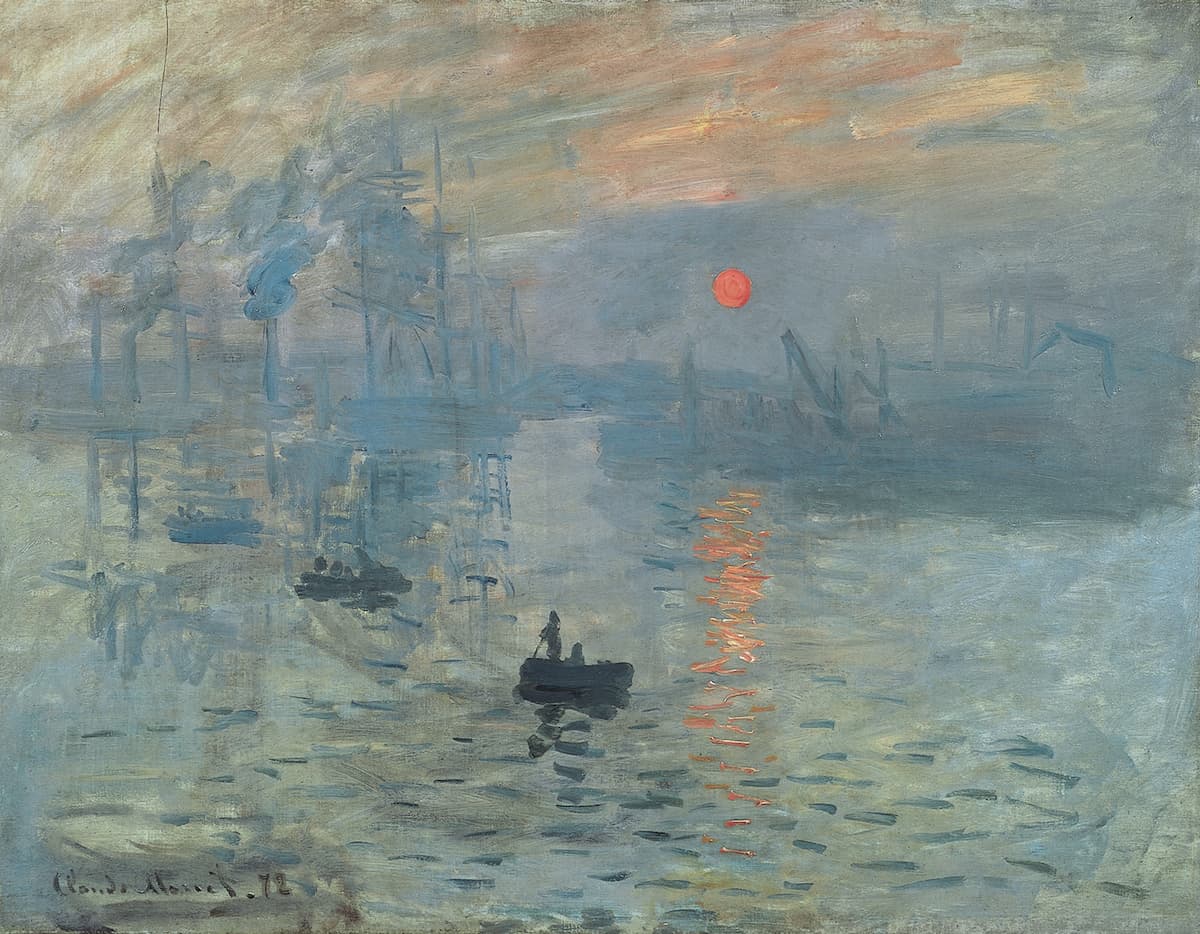

Debussy hated being called an impressionist composer. Impressionism in painting had been given its name based on the title of a Monet picture, Impression, soleil levant (Impression: Sunrise), the painters preferred to regard themselves as realists, showing the world in all its momentary and transient glory. Debussy argued that, in a similar vein, his music was realism of the auditory kind. His argument didn’t carry – the impressionism name, although originally intended as a sarcastic comment by a critic who viewed the painting by Monet as, at best, a sketch, was too good to set aside.

Nadar: Debussy, 1902 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

One of Debussy’s most famous works was his 1894 Prelude to a Poem, i.e., his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, which should really be read as Prélude à ‘l’après-midi d’un faune’, since it was Mallarmé’s poem, ‘L’après-midi d’un faune’, about which Debussy was writing his Prélude. Rather than a prelude in the Bachian sense, Debussy’s Prélude was actually a symphonic poem. Debussy wrote about this work:

The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads, he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature.

Claude Monet: Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), 1872 (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet)

Debussy wasn’t seeking to set the poem line by line but to read behind the poem to depict the eroticism of Mallarmé’s text.

L’APRÈS-MIDI | The Afternoon |

D’VN | of a |

FAVNE | Faune |

Églogve | Eclogue |

LE FAVNE | The faun: |

Ces nymphes, je les veux perpétuer. | These nymphs, I would perpetuate them. |

Si clair, | So bright |

Leur incarnat léger, qu’il voltige dans l’air | Their crimson flesh that hovers there, light |

Assoupi de sommeils touffus. | In the air drowsy with dense slumbers. |

Aimai-je un rêve ? | Did I love a dream? |

In just these first lines, Mallarmé evokes the sleepy faun, the brightly coloured images that were dancing before his eyes, and his question about his own state: waking or dreaming. And so, Debussy picks up many of those same elements: fluid runs in the flute that seems almost improvisatory to catch the sleepy faun’s dream state, shifts in time between 9/8, 6/8, and 12/8, using a base-3 system for the relationship between time signatures, use of extended sections in whole-tone, where every pitch is 1 step away from its neighbours.

Debussy’s deliberate orchestration – moving the initial melody from the mellifluous flute to the most nasal-sounding oboe changes the character of the opening melody, the use of lower strings such as the viola for a darker sound, and so on.

The 110-lines of Mallarmé’s verse are matched with 110 bars of Debussy’s music. The different editions of the poem between 1876 and 1914 can be examined here.

Mallarmé’s friend, the artist Édouard Manet, created four wood-engraved illustrations for the publication in 1876. They were printed in black and then hand-tinted in pink by Manet himself in order to save Mallarmé money.

Manet: Frontispiece for L’après-midi d’un faune, 1876 (Bibliothéque national)

Claude Debussy: Prelude A L’apres-Midi D’un Faune

This 1960 recording was made at the Grosser Saal at the Konzerthaus, Vienna, with Edouard van Remoortel leading the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Van Remoortel (1926-1977) was a Belgian conductor who worked with the Belgian National Orchestra as of 1951. From 1958 to 1962, he was music director with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra but was driven out by disagreements with the orchestra so much that at that point, they refused to play under his direction. The Vienna Symphony Orchestra (now the Vienna Symphony), was founded in 1900 and has been based at the Konzerthus in Vienna since 1913.

Performed by

Edouard van Remoortel

Orchestre Symphonique de Vienne

Recorded in 1960

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter