From his glorious summation of 19th-century Romanticism to the deeply probing psychological experimentations of 20th-century Modernism, the long career of Richard Strauss spanned one of the most chaotic political, social, and cultural periods in human history. Composing in all genres, Richard Strauss almost exclusively expressed his life and thoughts through music and the arts. Towards the end of his life Richard Strauss summed up his artistic legacy by stating, “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!” This deceptively lighthearted self-assessment brings into focus Strauss’s role in the growing rift between the 19th century bourgeois conception of an artist and composer, and the rapidly encroaching modernist perspective of the 20th. It also adversely affected the reception of his music and his person. Strauss made his name with a series of experimental tone poems that are now mainstays of the orchestral repertoire, while the operas that followed such as Salome, Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier remain operatic staples to this day. The popularity of these works should not detract, however, from the fact that Richard Strauss had always been a controversial figure. Accused of an excess of ironic detachment by friends and critics alike, his elegantly crafted and astonishingly appealing music was frequently classified as kitsch.

From his glorious summation of 19th-century Romanticism to the deeply probing psychological experimentations of 20th-century Modernism, the long career of Richard Strauss spanned one of the most chaotic political, social, and cultural periods in human history. Composing in all genres, Richard Strauss almost exclusively expressed his life and thoughts through music and the arts. Towards the end of his life Richard Strauss summed up his artistic legacy by stating, “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!” This deceptively lighthearted self-assessment brings into focus Strauss’s role in the growing rift between the 19th century bourgeois conception of an artist and composer, and the rapidly encroaching modernist perspective of the 20th. It also adversely affected the reception of his music and his person. Strauss made his name with a series of experimental tone poems that are now mainstays of the orchestral repertoire, while the operas that followed such as Salome, Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier remain operatic staples to this day. The popularity of these works should not detract, however, from the fact that Richard Strauss had always been a controversial figure. Accused of an excess of ironic detachment by friends and critics alike, his elegantly crafted and astonishingly appealing music was frequently classified as kitsch.

“Richard Strauss the composer and man juxtapose the trivial and the sublime, and the extraordinary with the everyday.” The key to an understanding of his music may not be found in an attempt to reconcile or resolve these contradictions, but rather in the composer’s own musical celebration of this duality. Most importantly, Strauss recognized the inability of contemporary art to maintain a unified mode of expression, and he eagerly confronted and musically addressed this fundamental issue of modernity. Although Glenn Gould suggested that Strauss and Schoenberg were the two greatest composers of the century, serious scholarly interest in Richard Strauss had to wait until the last decade of the 20th century. For noted Richard Strauss scholar Bryan Gilliam, the composer poses a unique challenge in modern music. “The ideal likeness of Strauss,” he suggests, “would not be a painting, drawing, or sculpture, but it would be a mosaic, coherent from afar, but upon closer view made of numerous contrasting fragments.”

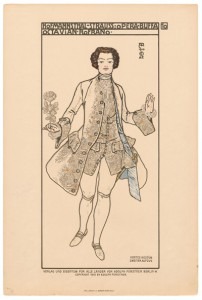

In terms of audience appeal, nothing comes close to Der Rosenkavalier of 1911. Collaborating once more with Hofmannsthal, Strauss tuned to 18th-century Vienna and the musical world of Mozart. This comic opera presents a critical layering of musical styles, referencing Mozart, Verdi, and the waltzes—evoking a sense of sentimentality and denoting middle-class sensibilities—of Johann Strauss. “Strauss essentially discloses his modernist preoccupation with the dilemma of history, and the popularity of the score has overshadowed the theatrical brilliance and modernity of the work.” The 1911 Dresden premiere was one of the most anticipated musical and cultural events in the first half of the 20th century. Additional trains from Berlin and elsewhere had to be added to handle the increased traffic of a curious public trying to experience this new artistic wonder. Within a couple of months, most capitals in Europe had mounted productions, and the 1917 catalog of the London publisher Chappell and Co. listed no fewer than 44 arrangements of music from the opera, ranging from brass band to salon orchestra, from solo mandolin to full symphony. By 1924, five years before the introduction of sound movies, the opera had been made into a silent motion picture under the direction of Robert Wiene, with a pit orchestra providing an abbreviated score. Given the orchestral virtuosity of the score and its hauntingly beautiful and infectious melodies, Richard Strauss was asked to fashion an orchestral condensation for the concert hall. Somewhat reluctantly, the composer agreed and produced a delightful First Waltz Sequence.

However, the Rosenkavalier Suite most frequently performed today was actually collated by Artur Rodzinski, conductor of the New York Philharmonic, in 1944. At first, Richard Strauss strongly objected to this additional arrangement of the score, but given the composer’s financial difficulties after WWII, he finally consented to its publication in 1945. Rodzinski’s arrangement provides a most satisfying bird’s-eye view of the entire score. Depicting the night of passion between the Marschallin and Octavian, the suite opens with the opera’s orchestral prelude. The music next introduces us to the Marschallin, and also to Octavian as the Rosenkavalier. In the rapturous scene of the presentation of the rose, Octavian and Sophie declare their love for each other, only to be interrupted by the clumsy arrival of Baron Ochs. Musical monologues by the Marschallin, Octavian and Sophie, each reflecting on love from their different points of views, is followed by the final duet between Octavian and Sophie as they waltz into the sunset together. This glittering succession of delectable and ravishingly beautiful waltzes melancholically references the elegance, refinement, opulence and charm of Vienna’s bygone golden age. Sparkling with the effervescence of musical champagne, the Rosenkavalier Suite reminds us that Richard Strauss was the most popular composer of his day. The Rosenkavalier Suite was first staged only five years before Strauss’s death, and the final trio was performed under the baton of George Solti at the composer’s memorial service at the Ostfriedhof in Munich.

The Rosenkavalier Suite will be performed at the HK Phil Season Opening Concert.

Richard Strauss: Rosenkavalier Suite

More Inspiration

-

Henry David Thoreau: Walden Discover how Henry David Thoreau's Walden inspired classical composers

Henry David Thoreau: Walden Discover how Henry David Thoreau's Walden inspired classical composers - Whispers of Love and Loss

Schumann’s Liederkreis, Op. 24 (Part 2) How Heine's romantic irony and Schumann's musical sensitivity create this masterwork - Whispers of Love and Loss

Schumann’s Liederkreis, Op. 24 (Part 1) We analyze the love, loss, and romantic irony in German Lied tradition -

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms