Maurice Ravel

The undisputed masterwork to emerge from the Wittgenstein commissions was the Concerto pour la main gauche by Maurice Ravel. Yet the collaboration between composer and interpreter was decidedly acrimonious. Composed between 1929 and 1930, Ravel was intrigued by the challenge and “wrote a concerto containing many jazz effects. In a work of this kind,” Ravel admitted to his publisher, “it is essential to give the impression of a texture no thinner than that of a part written for both hands. For the same reason, I resorted to a style that is much nearer to that of the more solemn kind of traditional concerto.”

Initially, Wittgenstein was not impressed and made a number of musical and pianistic changes to the score. This in turn infuriated Ravel, who drafted a formal and legally binding contract demanding that his work was henceforth to be played strictly as written. Ravel had forged an unbreakable connection between his artistic creativity embodied in the concept of the musical work and the musical text as represented by the score. The pianist, in turn, was clearly not content to be merely a part of the coloristic subtleties of Ravel’s orchestra, and demanded his interpretive liberties. It took Wittgenstein a good while before he was able to appreciate the composition. “It always takes me a while to grow into a difficult work,” he wrote. “ I suppose Ravel was disappointed, and I was sorry, but I had never learned to pretend. Only much later, after I’d studied the concerto for months, did I become fascinated by it and realized what a great work it was.”

Initially, Wittgenstein was not impressed and made a number of musical and pianistic changes to the score. This in turn infuriated Ravel, who drafted a formal and legally binding contract demanding that his work was henceforth to be played strictly as written. Ravel had forged an unbreakable connection between his artistic creativity embodied in the concept of the musical work and the musical text as represented by the score. The pianist, in turn, was clearly not content to be merely a part of the coloristic subtleties of Ravel’s orchestra, and demanded his interpretive liberties. It took Wittgenstein a good while before he was able to appreciate the composition. “It always takes me a while to grow into a difficult work,” he wrote. “ I suppose Ravel was disappointed, and I was sorry, but I had never learned to pretend. Only much later, after I’d studied the concerto for months, did I become fascinated by it and realized what a great work it was.”

Maurice Ravel: Concerto pour la main gauche

Wittgenstein premiering Schmidt’s Concerto for the left hand, Feb 1935

If Wittgenstein initially found fault with Ravel’s musical modernism, he certainly found his compositional soul mate in Franz Schmidt. Wittgenstein demanded tailor-made compositions that exhibited a sense of embodied virtuosity. This natural consequence of his desire for artistic and musical autonomy was supported by Schmidt’s musical styles and techniques that never thought to emulate the pianistic mannerisms associated with two hands. In essence, Schmidt composed a piano part that was idiomatically tailored for Paul Wittgenstein’s left hand, and he treated the left-hand piano as a new and original instrument. For Wittgenstein and Schmidt, the line of demarcation between creative and re-creative roles was an easily crossed boundary. And both knew their respective roles. Schmidt was clearly the better composer, but Wittgenstein the far superior left-hand pianist. Schmidt skillfully evokes Lullabies, Waltzes, Toccatas, Serenades, Ländlers and Hungarian Folk tunes in textures ranging from free-flowing single musical lines and homophonic simplicity, to passages of an intensely contrapuntal nature. Although musically conservative, their collaborations uncovered those points of contact between their respective arts that allowed them to forge a compelling synthesis between musical inspiration and performance. For Wittgenstein, Schmidt’s works became the blueprint of what left-hand pianism could and should be. When he commissioned Benjamin Britten, Wittgenstein handed him Schmidt’s E-flat concerto as a compositional aid. I don’t think the young Englishman was particularly impressed!

Franz Schmidt: Piano Concerto in E-flat for piano left hand and orchestra

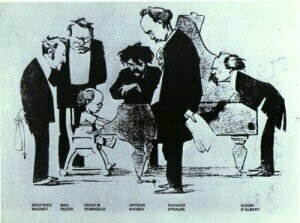

He was called the “Little Korngold,” and his phenomenal musical ability was the talk of coffeehouses and salons in Vienna. Erich Wolfgang, son of the feared music critic Julius Korngold, was a prodigious musical genius who ignited the public’s imagination with the premiere of the full-fledged “Snowman” pantomime at the age of 13. He certainly aroused the admiration of Gustav Mahler, Arthur Nikisch, Bruno Walter and Richard Strauss. With the premiere of his opera Die tote Stadt, Korngold was at the height of his fame, and when Paul Wittgenstein approached him for a large-scale piano concerto, he happily accepted.

He was called the “Little Korngold,” and his phenomenal musical ability was the talk of coffeehouses and salons in Vienna. Erich Wolfgang, son of the feared music critic Julius Korngold, was a prodigious musical genius who ignited the public’s imagination with the premiere of the full-fledged “Snowman” pantomime at the age of 13. He certainly aroused the admiration of Gustav Mahler, Arthur Nikisch, Bruno Walter and Richard Strauss. With the premiere of his opera Die tote Stadt, Korngold was at the height of his fame, and when Paul Wittgenstein approached him for a large-scale piano concerto, he happily accepted.

Korngold and Bruno Walter

Cast in a single-movement, Korngold’s refined art of instrumentation produces a work of outstanding radiance and brilliance. Within this brightly colored orchestral packaging, we find Korngold’s dynamic of motion embodied in a highly challenging piano part. Lyrical, seemingly improvisatory and certainly heroic, pianist Gary Graffman has called the work “an instrumental Salome.” Wittgenstein owned the exclusive performing rights to the Concerto until his death in 1961, and the work gradually disappeared from view. More recently, however, Gary Graffman, Marc-André Hamelin, Howard Shelley and Steven de Groote have reawakened this luscious beauty.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

Wonderful article, but I’m surprised there is no mention of either Prokofiev’s 4th or the Hindemith concerto, both commissioned by Wittgenstein and both delightful–and, at times, profound–works.