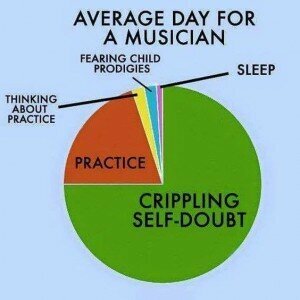

No-one said becoming a musician is easy. It takes years of practice, discipline, and a unique personality—of humility, to convey the composer’s intention as best we can, and self-confidence, to walk onto the stage and play with panache. But no matter how talented or diligent we are, doubt creeps in, “What am I doing on this stage? Am I really good enough?” It doesn’t help that society believes a career as a doctor, lawyer, or scientist is superior to dedicating our life to music. Even our parents plead, “When are you going to get a real job?” The measure of the quality or contribution of an artist has never been about making big bucks. We do it because it is us; it is our passion.

No-one said becoming a musician is easy. It takes years of practice, discipline, and a unique personality—of humility, to convey the composer’s intention as best we can, and self-confidence, to walk onto the stage and play with panache. But no matter how talented or diligent we are, doubt creeps in, “What am I doing on this stage? Am I really good enough?” It doesn’t help that society believes a career as a doctor, lawyer, or scientist is superior to dedicating our life to music. Even our parents plead, “When are you going to get a real job?” The measure of the quality or contribution of an artist has never been about making big bucks. We do it because it is us; it is our passion.

Success in a creative field is not magical, not due to some enchanted potion, not due to talent alone. Despite years of constant striving and hard work we suffer letdowns at every level. Here are some tips to quell imposter syndrome and achieve your musical dreams.

Too much music!

There are days when I don’t want to practice; days when I want to throw the music, my cello, and then myself out the window; days when I think I’ll never be able to play a passage. When the little voice in your head asks, “Am I ever going to be good enough?” take a breather, then resolve to go back to it. Practice, persistence, and patience are requirements.

Avoid mindlessly playing through pieces. After warming up, begin your practice somewhere other than the start of the piece. Tackle the most troublesome spots, which need slow, careful analysis, and figure out what isn’t working. When you observe with sharpness, and evaluate critically and impartially, it pays off.

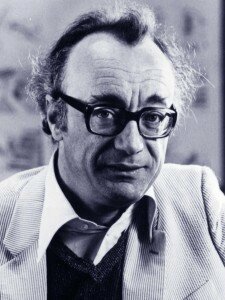

Alfred Brendel

Stop to correct out of tune notes. Intonation is like being pregnant. You are not more pregnant or less pregnant. Either you are or you aren’t. Whatever you do is reinforced in the brain—right or wrong.

Make certain your rhythm is solid. We tend to speed up when we are nervous or when a passage is really difficult. Practice with a metronome and choose a sane tempo—one that you can play from start to finish. Don’t attempt Rostropovich’s tempo in Elfentanz at home!

Rostropovich plays Elfentanz

Be on the lookout for any tension in your body. Aim for technical ease and sit with good posture. The musical intention of the work is conveyed more easily and effectively with minimal effort.

If you’re fortunate, on the road to becoming a musician you encounter a good teacher, and musical mentors who guide and inspire you. Choose them carefully. Your instructor should motivate you to attain the highest levels, and help you learn how to be your own teacher and advocate. It is critical your relationship is one of mutual respect. Be wary of anyone who belittles you or insists on a dogmatic way of doing things.

Develop relationships. Deliberate interaction with colleagues and the audience will enrich your performance and help you understand what is working, and what might not be. We often feel we have to prove ourselves every time we get on the stage. But it’s not about us. It’s about the music and communicating the emotions of the piece we are playing. I find it helps to develop a vocabulary of adjectives to trigger the “feel” I wish to convey. I write them in the music. Are you trying to impart despair or delight? Anguish or serenity? Tenderness or malice? In the heat of performance, if your mind goes blank with nerves, these words can guide you back to the music. Focus on touching the audience. Remind yourself that there might be someone who will be uplifted, who needs your music.

Develop relationships. Deliberate interaction with colleagues and the audience will enrich your performance and help you understand what is working, and what might not be. We often feel we have to prove ourselves every time we get on the stage. But it’s not about us. It’s about the music and communicating the emotions of the piece we are playing. I find it helps to develop a vocabulary of adjectives to trigger the “feel” I wish to convey. I write them in the music. Are you trying to impart despair or delight? Anguish or serenity? Tenderness or malice? In the heat of performance, if your mind goes blank with nerves, these words can guide you back to the music. Focus on touching the audience. Remind yourself that there might be someone who will be uplifted, who needs your music.

I admit I was a bit cocky in my younger days. During my first season as associate principal cello of the Minnesota Orchestra, Alfred Brendel was our soloist. His masterful playing of Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 led me, after the rehearsal, to ask him if he’d like to read the Beethoven Cello Sonatas. The look he gave me traveled all the way down to my toes. That evening, during the performance, he hurled his piano rack up with such force I knew it was to avoid seeing me at the other end of the piano! Be humble. Countless artists have played the music you are trying to learn. Be prepared to hear other approaches and ideas.

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 (Alfred Brendel)

Every decision creates a different color, or character in the music. If a phrase is repeated, play it louder or softer, without vibrato or with a distinctive quality of sound, a different fingering or bowing, or in an altered mood. Always search for new depths of expression from one performance to the other. The most successful artists such as the great piano virtuoso Mitsuko Uchida, are devoted. “How I’ve changed in myself is difficult to say. One thing is clear: I have always stayed a student. I’ve just got older. I’m basically someone who studies and who tries hard every day.” Never imitate the style of another performer. An audience can sense if you are fabricating airs or emotions. Always remain authentic to yourself, your unique artistic identity, and aim for consistent growth.

Think of yourself as a raconteur telling a story, striving for phrases not bound by words or this world. We performers are re-creators, bringing the composer’s intentions to life infused with our own souls.

When you miss something don’t dwell on it. The errors you hear are more fleeting than you think and the audience probably won’t even notice! Sir Simon Rattle recently said, “Everyone messes up at some point. It’s how you deal with it that matters…Work like hell, stay curious, and realize that people around you actually…are very supportive…We all started there and we’ve all been in it.”

Playing an instrument requires the nerves of a bullfighter, the vitality of a marathon runner, and the concentration of a brain surgeon, but when you play with intention, music has a powerful impact. You don’t have to attain “name-in-lights” stature. Famed pianist Menahem Pressler sums it up beautifully, “you can sit in a small town and teach, and find not only satisfaction, but the feeling that when you transmit music to someone else and reach their lives, you have really done something important in your life.” That will always be good enough.