Orpheus and Eurydice

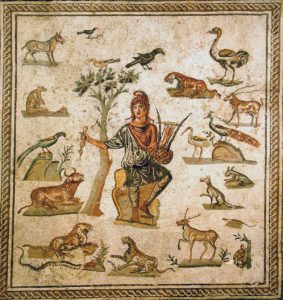

Orpheus was not only a legendary hero of Greek mythology; he was also the first superstar musician. But more than that, he was the Mozart, Shakespeare, Pavarotti, and Lady Gaga all rolled into one. His singing and playing moved even wild beasts and inanimate rocks to tears, and rivers diverted their courses just to hear him. It was said that his character matched the sweetness of his playing and singing, and that he performed for the love of music and for the celebration of the beauty of the world and the glory of love. There is considerable variation in the story of how he met and married the beautiful Eurydice, but everybody agrees that she was bitten by an angry viper and perished.

Orpheus took his golden lyre and descended into the Underworld, where he first charmed the hellhound Cerberus, the ferryman of death Charon and eventually melted the hearts of Hades, the King of the Underworld, and his consort Persephone. They eventually agreed that Orpheus could take his beloved Eurydice back to the world of the living, but under the condition that he doesn’t turn back to look at his wife until he has reached the world of the living. And since Orpheus was a flawed mortal, he miserably failed his task.

Orpheus took his golden lyre and descended into the Underworld, where he first charmed the hellhound Cerberus, the ferryman of death Charon and eventually melted the hearts of Hades, the King of the Underworld, and his consort Persephone. They eventually agreed that Orpheus could take his beloved Eurydice back to the world of the living, but under the condition that he doesn’t turn back to look at his wife until he has reached the world of the living. And since Orpheus was a flawed mortal, he miserably failed his task.

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo (Kobie van Rensburg, tenor; Cyrille Gerstenhaber, soprano; Estelle Kaique, mezzo-soprano; Philippe Jaroussky, counter-tenor; Renaud Delaigue, bass; Delphine Gillot, soprano; Bernard Deletre, bass; Philippe Rabier, baritone; Hjordis Thébault, mezzo-soprano; Lorraine Prigent, soprano; Alain Bertschy, tenor; Vincent Bouchot, baritone; Carl Ghazarossian, tenor; Thierry Gregoire, counter-tenor; Pierre Yves Pruvot, baritone; Grande Écurie et la Chambre du Roy; Jean-Claude Malgoire, cond.)

Orpheus before Hades

The legend of Orpheus and his fruitless attempt to bring his dead bride Eurydice back to the world of the living is central to the emergence of opera in the late Italian Renaissance. Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) was working as a court musician in Mantua when his wife Claudia passed away in 1607. Experiencing intense grief and despair, his emotional state mirrored the circumstances of the Orpheus of Greek mythology, “who suffers, loves, exults, mourns, goes on a heroic rescue mission, stumbles at the last hurdle and finally reaches a new and deeper understanding of himself.” Having already worked in Mantua for 16 years, Monteverdi had a thorough grounding in theatrical music. The individual elements, including the aria, the strophic song, recitative, choruses, dances, and dramatic musical interludes that make up Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo score, are blended into a “favola in musica,” simply indicating that all actors are singing their parts. And while Monteverdi might be surprised to find himself hailed as the inventor of the opera, L’Orfeo is a radically innovative and extraordinary work. Whether we should reasonably call him the “creator of modern music” is a matter of semantics. What is undisputed is the fact that Monteverdi developed powerful ways of expressing and structuring musical drama.

Luigi Rossi: Orpheus (excerpts) (I Baroque; Diego Fasolis, cond.; Emőke Baráth, soprano; Philippe Jaroussky, counter-tenor; Swiss Radio Choir, Lugano; Lorenza Donadini, soprano; Caterina Iora, soprano; Alice Rossi, soprano; Isabella Hess, vocals; Bérengère Sardin, harp)

The myth of Orpheus was the subject to numerous adaptations during the seventeenth century. Luigi Rossi’s Orfeo, first performed in Paris in 1647 introduced a number of comical elements, including the goddess Venus disguised as an old nurse. Orpheus was clearly endowed with superhuman musical skills, but he nevertheless was a flawed and arrogant mortal, who sincerely believed that he could cheat death. And it was that juxtaposition of weakness, insecurity and charisma that prompted numerous composers to probe human nature and desire by means of music. “The fact that music is capable of fluid, imperceptible change and harmonic modulation gives it the facility to straddle one realm of existence and the next.” Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) tried his hands at opera by composing the cantata Orphée at some point before 1721. He created a multi-layered drama of love, doubt and loss in extended arias and bold recitatives.

The myth of Orpheus was the subject to numerous adaptations during the seventeenth century. Luigi Rossi’s Orfeo, first performed in Paris in 1647 introduced a number of comical elements, including the goddess Venus disguised as an old nurse. Orpheus was clearly endowed with superhuman musical skills, but he nevertheless was a flawed and arrogant mortal, who sincerely believed that he could cheat death. And it was that juxtaposition of weakness, insecurity and charisma that prompted numerous composers to probe human nature and desire by means of music. “The fact that music is capable of fluid, imperceptible change and harmonic modulation gives it the facility to straddle one realm of existence and the next.” Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) tried his hands at opera by composing the cantata Orphée at some point before 1721. He created a multi-layered drama of love, doubt and loss in extended arias and bold recitatives.

Jean-Philippe Rameau: Orphée (excerpts) (Sunhae Im, soprano; Berlin Akademie für Alte Musik)

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) first entered onto the operatic stage with a merry Germany Singspiel “Der krumme Teufel” (The crooked Devil) in the 1751/52 Viennese season. It was the beginning of Haydn’s prolific operatic productions that spanned a period of roughly four decades. His last opera L’anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice was composed to a libretto by Carlo Francesco Badini. Badini tweaked the original story, adding a dramatic closing scene in which Orpheus drinks a cup of poison following his failed rescue attempt. The legend of Orpheus and the re-worked libretto provided Haydn with the opportunity for the employment of lush orchestral writing, a wealth of choruses, and extremely expressive arias. The psychologically complex material of the Orpheus legend not only inspired the beginning stages of opera, it is being rediscovered by various multi-media artists in the 21st century.

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) first entered onto the operatic stage with a merry Germany Singspiel “Der krumme Teufel” (The crooked Devil) in the 1751/52 Viennese season. It was the beginning of Haydn’s prolific operatic productions that spanned a period of roughly four decades. His last opera L’anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice was composed to a libretto by Carlo Francesco Badini. Badini tweaked the original story, adding a dramatic closing scene in which Orpheus drinks a cup of poison following his failed rescue attempt. The legend of Orpheus and the re-worked libretto provided Haydn with the opportunity for the employment of lush orchestral writing, a wealth of choruses, and extremely expressive arias. The psychologically complex material of the Orpheus legend not only inspired the beginning stages of opera, it is being rediscovered by various multi-media artists in the 21st century.

Franz Joseph Haydn: L’anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice (Helen Donath, soprano; Robert Swensen, tenor; Sylvia Greenberg, soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Paul Hansen, baritone; Atzuko Suzuki, soprano; Meng-Chia Eng, vocals; Dankwart Siegele, bass; Wilfried Vorwold, bass; Jurgen Weiss, vocals; Roland Kandlbinder, tenor; Bavarian Radio Chorus; Munich Radio Orchestra; Leopold Hager, cond.)