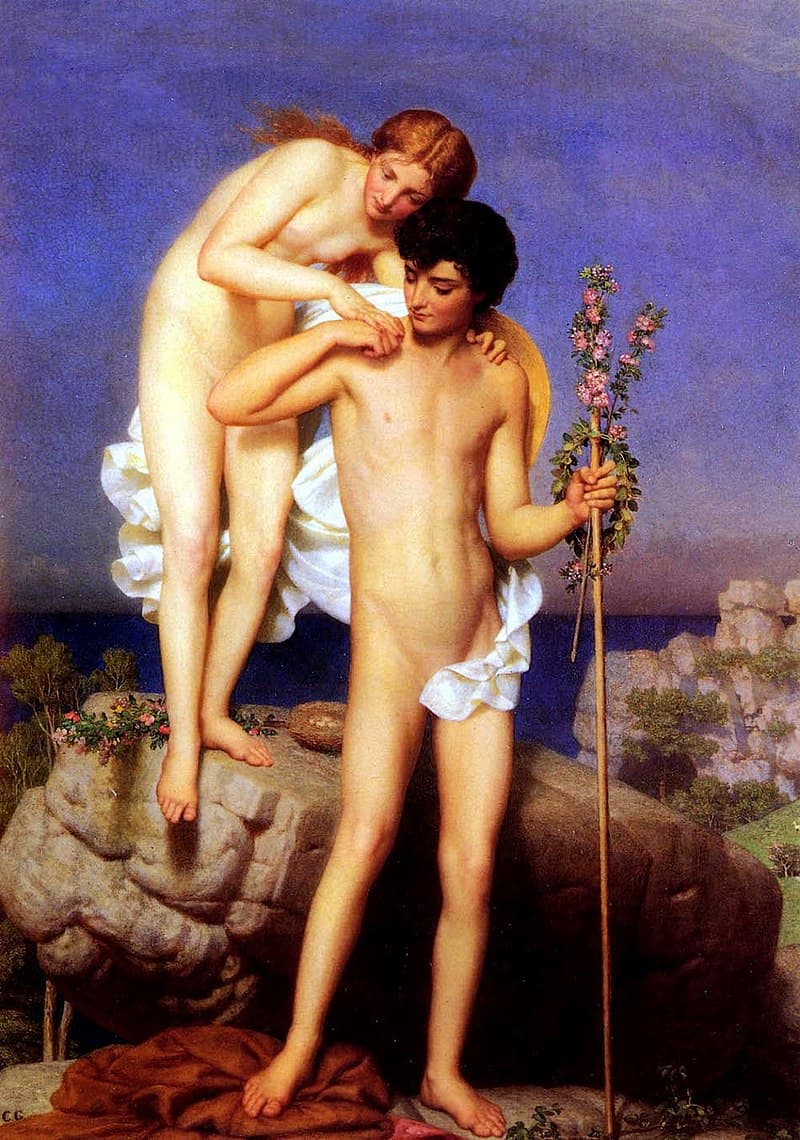

Set on the Greek isle of Lesbos, the ancient Greek novel Daphnis et Chloe is a pastoral tale of shepherds and shepherdesses authored by the Greek writer Longus. It tells the story of a boy and a girl, each abandoned at birth. One shepherd family adopts Daphnis, and another family Chloe. They do grow up together herding the flocks for their foster parents. When they fall in love they can’t understand what is happening to them.

Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre: Daphnis and Chloe (c. 1850)

A wise old cowherd explains to them about love, and he tells them that the only cure is kissing. As they start kissing, a nymph educates the seriously naïve Daphnis on the art of making love, but he decides not to pressure Chloe. Meanwhile, Chloe is courted by various suitors and eventually abducted, but saved by the intervention of the god Pan. In the meantime, Daphnis gets beaten up and abducted by pirates, and nearly raped by a drunkard. Eventually both are recognized by their birth parents, and Daphnis and Chloe get married and live a happy country life.

Maurice Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé, Suite No. 1 “Nocturne”

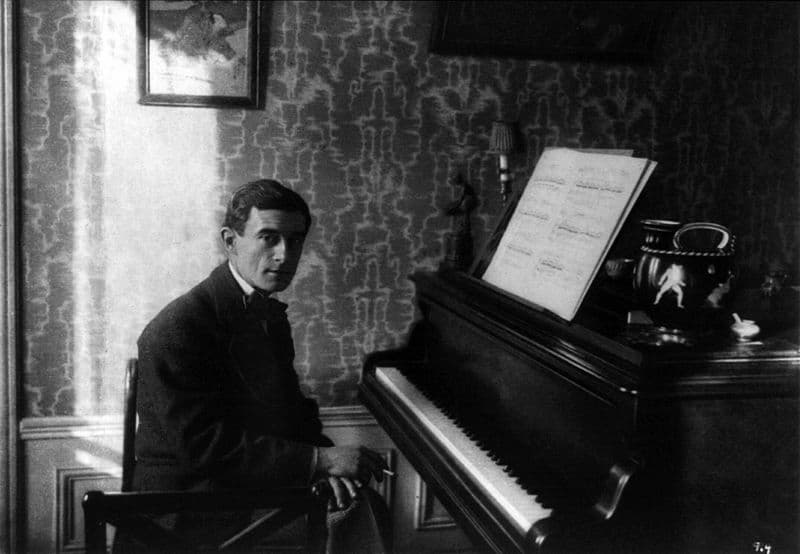

On 8 June 1912 a reimagined version of this lusty tale, cast as a symphonie chorégraphique for orchestra and wordless chorus, premiered at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. Aptly titled Daphnis et Chloé, the project had been the brainchild of Sergei Diaghilev especially envisioned for his Ballets Russes. Maurice Ravel composed the music, Léon Bakst designed the sets, Fokine provided the choreography, and Tamara Karsavina and Vaslav Nijinsky danced the roles of Daphnis and Chloe. It had taken Diaghilev and Ravel nearly three years of planning and composing. And while the official commission was issued in 1909, the inception of the project most likely dates back to 1907. As the music critic, musicologist, and personal friend of Ravel, Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi remembered, “Ravel with Diaghilev, Fokine, Bakst, Benoir and myself in Diaghilev’s little sitting room at the Hotel de Hollande in 1907. It was then finally decided on Daphnis, and everybody offered suggestions as to particulars of the plot.”

Maurice Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé, Suite No. 1 “Interlude” (Slovak Philharmonic Chorus; Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Kenneth Jean, cond.)

Sergei Diaghilev

In the event, a serious disagreement arose between Ravel and Fokine, because each was aiming at a different ideal. As a scholar writes, “Ravel wanted to create a vast musical fresco, less concerned with archaism than with fidelity to the Greece of his dreams, which is close to that imagined and painted by the French artists of the late eighteenth century.” Fokine, on the other hand, was looking “to recapture, and dynamically express, the form and image of the ancient dancing depicted in red and black on Attic vases.”

Maurice Ravel at the piano, 1912

Ravel had read the story in an eighteenth-century translation, and in the end, he got his wish with the result that “nothing ultimately is less Greek than this Daphnis. All questions of fidelity to the Greek novel were swept aside, and in the final three-part scenario, very little remains of the details of the original.” According to Ravel’s wishes, the production turned out to be “a ballet of contrasting neoclassicisms, its visual layer composed of flowing line and bright colors, its aural layer of floating motives and blended timbres.”

Maurice Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé, Suite No. 1 “Danse guerrière” (Minerva Piano Trio)

Léon Bakst’s set design for Act 1 of “Daphnis et Chloe”, 1912

Leading the work to its premiere turned out to be a challenge. When piano rehearsals started in May 1912, Diaghilev wanted to cancel the whole project because he severely disliked the music. He was eventually placated by Durand’s assurance that “Ravel’s orchestration would bring the music to life.” For one reason or another, Fokine and Bakst got into a quarrel, and the work was originally scheduled for four performances between 5 June and the last evening of the season on the 10th.

A band of pirates from the Ballets Russes premiere of Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé, Scene II.

However, Daphnis “was elbowed out of the first two by L’après-midi d’un faune and thus restricted to just two performances without even a dress rehearsal.” Ravel was furious at having the expected four performances reduced to two, and while there has never been a definitive explanation, Diaghilev “clearly had no love for Daphnis.” John Drummond has perhaps provided the most likely reason, and it is a purely artistic one. “Daphnis has huge tableaux, in which nothing much happens, and then crucial episodes of the narrative compressed into tiny sections, with hardly enough notes to let the action take place.” Ravel might have had similar thoughts, as he extracted music for two orchestral suites. The first was prepared in 1911, before the work was actually staged, and the second issued in 1913. Tellingly, he titled both “Fragments symphoniques de ‘Daphnis et Chloé.’”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter