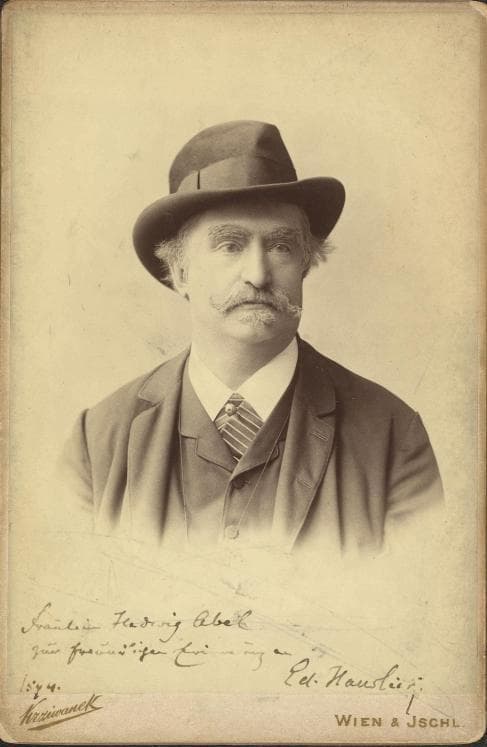

In 1874, Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904) submitted an application for an artist’s stipend from the Austrian government for poor but talented students. Hoping to supplement the meager income from his job as an organist at St. Adalbert, Dvořák first obtained a certificate of poverty from Prague City Hall, and together with a variety of musical scores sent the documents to the Ministry of Culture and Education in Vienna. The head of the selection committee was a close personal friend of Johannes Brahms, the highly influential Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick.

Antonín Dvořák

According to the committee, Dvořák’s works “display undoubted talent, but in a way which as yet remains formless and unbridled.” This somewhat ambiguous endorsement nevertheless was sufficient to bequeath Dvořák the highest available stipend of 400 Gulden, which the composer received in February 1875. The scores Dvořák submitted included, amongst others, Symphonies No. 3 and a newly completed work, his Symphony No. 4 in D minor, Op. 13.

Antonin Dvořák: Symphony No. 4 in D minor, “Allegro” (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

There seems to be some disagreement as to when the premier performance took place. According to one source, the third movement was included in a program at the New Town Theatre in Prague on 25 May 1874. That performance was conducted by Bedřich Smetana, and according to a critic, the music “enjoyed a very enthusiastic reception. If we were permitted to judge the entire symphony based upon this part alone we would not wish for anything else, but that the work be performed in its entirety, as soon as possible.”

Eduard Hanslick, 1874

However, it took another eighteen years before audiences heard the complete work, on 6 April 1892, performed by the National Theatre Orchestra and conducted by the composer himself. Dvořák had apparently revised his 4th Symphony at the end of 1887 and the beginning of 1888, but the score was not published until 1912. The Wikipedia page, meanwhile, contends that the entire symphony sounded on 25 May 1874. I suspect that that page is in need of clarification, but without primary sources at my disposal, it is impossible to tell.

Antonin Dvořák: Symphony No. 4 in D minor, “Andante sostenuto” (Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Libor Pešek, cond.)

Richard Wagner came to Prague in February 1863 and conducted excerpts from four of his operas. For Dvořák, this became an overwhelming and formative experience. As he wrote, “I was perfectly crazy about him, and recollect following him as he walked along the streets to get a chance now and again of seeing the great little man’s face.”

St. Adalbert, Prague

A scholar writes, “Dvořák’s interest in Richard Wagner and his music was not only a youthful vagary, and it by no means ended with the 1860s, but rather had a deeper dimension and was of a more lasting nature.” When Dvořák embarked on his 4th Symphony, Wagner was still accorded prominence in his musical thoughts, as he based the entire slow movement on his memory of the “Pilgrims Chorus” from Tannhäuser.

Dvořák’s Symphony No. 4 – Andante sostenuto e molto cantabile

To a commentator “the brass chorale of the “Andante sostenuto” is not only the expression of the devout Catholic Dvořák, but rather also a last act of reverence to Wagner and the sacred aura of Tannhäuser from whose influence he would distance himself from now on.”

Antonin Dvořák: Symphony No. 4 in D minor, “Scherzo-Allegro feroce”

While the opening movement bears the unmistakable fingerprint of Beethoven in its tonality and structure, it nevertheless presents a turning point in the development of Dvořák’s musical expression. To be sure, the composer begins to gradually establish a distinctive compositional style of his own. The “Scherzo” opens with a jagged introduction in a minor key that gives way to a chorus-like theme. For some observers, “this D Major escalation rounded out by the harps, in particular, radiates patriotic splendor.”

Dvořák’s Symphony No. 4 – Scherzo (Allegro feroce); D minor, Trio

The Trio makes a reference to Meistersinger, with the melody augmented by the military instruments of bass drum and cymbals. It’s been suggested that Smetana had “good reason to perform this rousing Scherzo in the midst of the Czech independence movement.” The “Finale” movement appears to be a continuation of the “Scherzo,” and Dvořák presents “combative rhythms, warm-hearted string melodies, and patriotic splendor.” According to a conductor, “Dvořák creates the prototype of a national symphony, for the way out of the passionate restlessness and the beginning of a radiant future for the Czech people.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonin Dvořák: Symphony No. 4 in D minor, “Finale: Allegro con brio” (London Symphony Orchestra; István Kertész, cond.)