The premiere performance of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem took place on 30 May 1962 at the consecration ceremony for the New Coventry Cathedral. The original fourteenth-century structure had been destroyed in a World War II bombing raid, and the work according to scholars represented “a conscious resolve on the composer’s part to put the experience of his entire creative activity to that date at the service of a passionate denunciation of the bestial wickedness by which man is made to take up arms against his fellow.”

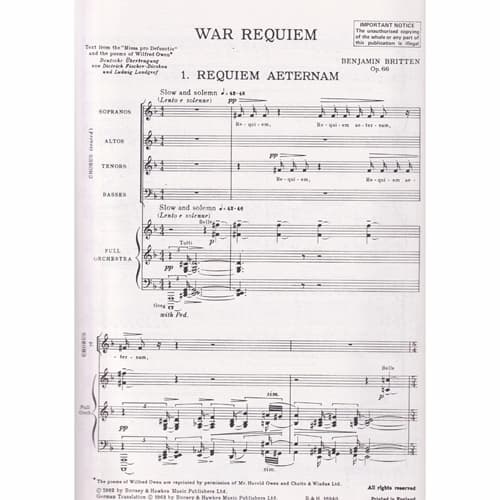

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, “Requiem aeternam”

Coventry Cathedral

The ruins of the Coventry Cathedral

The annals of Coventry Cathedral dated 16 November 1940 contain the following entry. “The whole building was a seething mass of flame and piled up blazing beams and timbers interpenetrated and surmounted with dense, bronze-coloured smoke. Through this could be seen the concentrated blaze caused by the burning organ, famous for its long history, back to the time when Handel played upon it.”

This horrendous atrocity had been the handywork of the German Luftwaffe, who reduced much of the city of Coventry to rubble during a heavy bombing raid. The Cathedral held no strategic importance, but it was solely targeted to demoralise the British people. The original structure was never rebuilt.

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, “Dies irae: Dies irae, dies illa” (The Bach Choir; London Symphony Chorus; Simon Preston, organ; Melos ensemble; London Symphony Orchestra; Benjamin Britten, cond.)

New Coventry Cathedral

Benjamin Britten

On the morning after the bombing raid, the decision was made to rebuild the cathedral. Provost Howard decided that the rebuilding would not be an act of defiance, “but rather a sign of faith, trust, and hope for the future of the world.” A design competition was initiated, but it was decided that the new cathedral should not be rebuilt in the Gothic tradition, nor that the new design should harmonise with the surviving tower and spire.

The contract went to the Scottish architect Basil Spence, known for designing the Sea & Ship pavilion on London’s South Banks. Not everybody was enthusiastic, but the new house of worship ingeniously incorporates the remains of the original in a modernist design. It took 16 years to finish the project, and the final structure was completed in May 1962.

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, “Offertorium”

Consecration Ceremony

Provost Howard in the ruins of the Cathedral on Christmas Day, 1940

With Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II scheduled to attend the consecration of the new cathedral, it was clear that the music had to play a major part in the celebrations. It was decided that the music should be “something upbeat, in the grand British choral tradition, and/or pastoral-peaceful, and signifying a future without conflict.”

A number of composers were considered, but in the end, the honour went to Benjamin Britten, Britain’s most internationally recognised composer. Britten was a pacifist and a conscientious objector, who had left England for the United States shortly before the entry into the war. He now accepted the commission, which gave him complete freedom in deciding what to compose.

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, “Sanctus” (Luba Orgonášová, soprano; Monteverdi Choir; North German Radio Chorus; North German Radio Symphony Orchestra; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

War Requiem

The New Coventry Cathedral

After a period of contemplation, Britten decided that the work would be a “memorial to the dead of all wars.” He selected the text of the Latin Requiem Mass, however, individual sections would be interspersed with nine poems by First World War poet Wilfred Owen. Owen was serving as the commander of a rifle company when he was killed in action on 4 November 1918, just one week before the Armistice.

The interaction of traditional Latin texts and Owen’s poetry resulted in highly subtle and powerful contrasts and ironies. We find apocalyptic visions of destruction, suffering, and the eternal, juxtaposed by deeply personal inner visions of the English solder-poet. As a scholar writes, “The combining of these two seemingly irreconcilable worlds creates a bitter irony that is uniquely Brittenesque.”

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, “Agnus Dei” (Lorna Haywood, soprano; Anthony Johnson, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, baritone; Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Chorus; Atlanta Boy Choir; Atlanta Symphony Orchestra; Robert Shaw, cond.)

Warning Unheard

Britten’s War Requiem vocal score

Britten divides the musical forces into three groups that alternate and interact with each other throughout the piece. Only at the end of the last movement are all forces fully combined. Musically speaking, Britten keeps the liturgical and profane works separate on the surface, but they are internally related through the employment of the tritone.

The War Requiem ends with words of peace, and at the head of the score Britten inscribed the solemn words with which Owen prefaced his poems:

My subject is War,

and the pity of War.

The poetry is in the pity.

All a poet can do is warn.

Given the desolate and barbaric destructions inflicted on civilian lives throughout 2024, that warning continues to be wilfully ignored.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter