By 1915, Alexander Scriabin was working on a gigantic multi-media project called Mysterium. It was intended for performance in the foothills of the Himalayas over a period of seven days. “Bells suspended from clouds would summon spectators. Sunrises would be preludes and sunsets codas. Flames would erupt in shafts of light and sheets of fire. Perfumes appropriate to the music would change and pervade the air, and the world would dissolve in bliss.”

Alexander Scriabin

Scriabin had managed to compose roughly seventy pages of music when septicemia took his life on 14/27 April 1915 (old and new Russian calendars) at the age of 43. Scriabin’s funeral was described as the most fashionable event in Moscow for years. The funeral was held two days after his death, and tickets had to be issued to The Church of the Miracle Worker in the Great Nikolo-Peskov Lane, in order to accommodate the public.

Alexander Scriabin: Mysterium “Prefatory Act”

As a biographer reports, the crowd grew continuously and entrance became impossible. The Church was decorated with trees and tropical flowers. The coffin of the deceased was submerged in wreaths and flowers. The music was specially chosen. Only the most beautiful voices of the Synodical Choir were selected, and they sang, as Rachmaninoff later commented, “with particular beauty.” Modern religious works by Kastalsky were sung, and an ancient Russian setting of the Lord’s Prayer. For weeks on end, newspapers were filled with memorial testimonies, formal obituaries, spontaneous poems, sonnets, and words of condolences. The playwright Nikolai Evreinov composed the following poem:

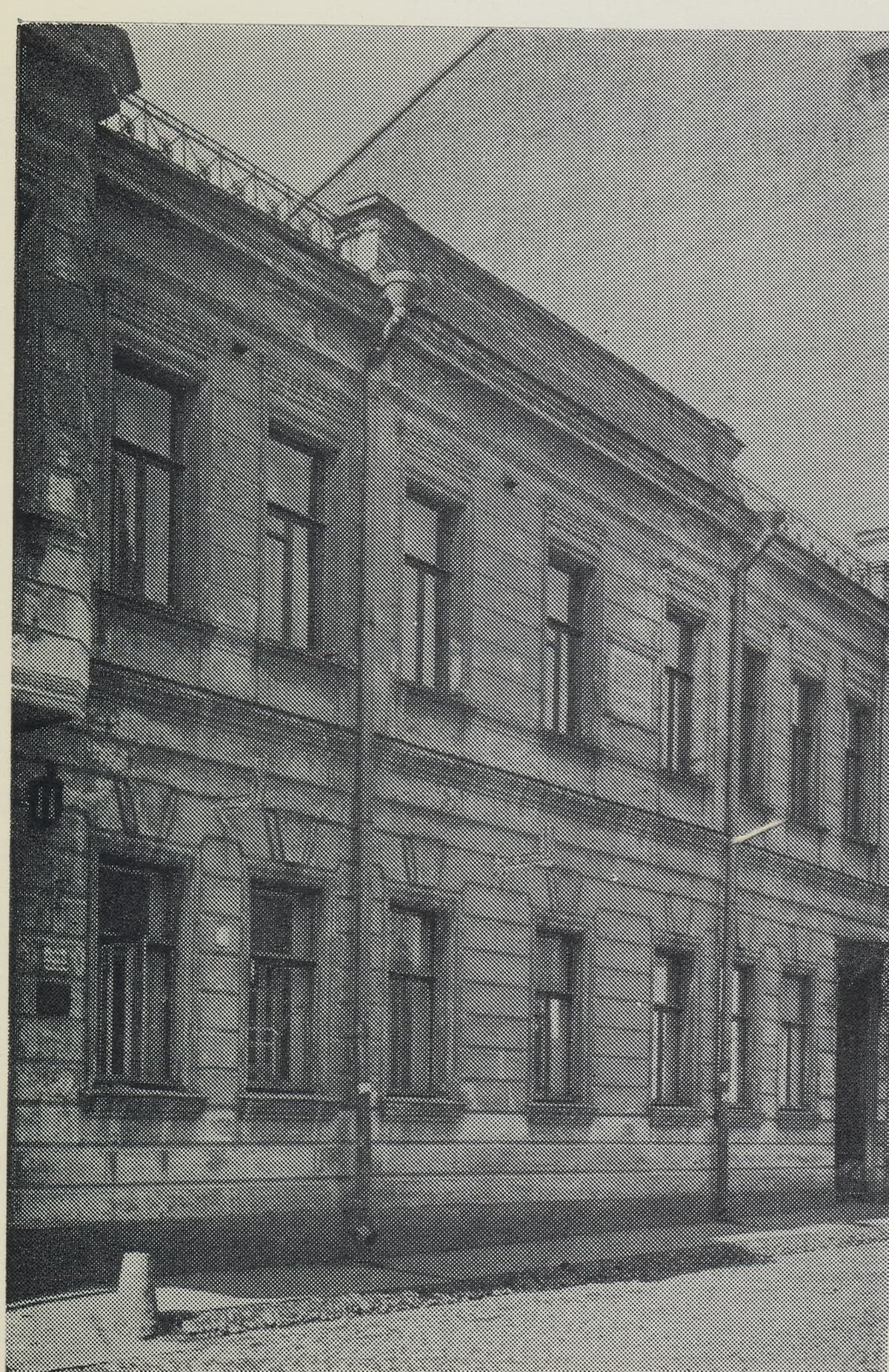

Alexander Scriabin’s last appartment

The sooner the flesh of genius dies, the sooner the soul returns to freedom.

Our bodies are a prison, a grave.

In truth, death is our resurrection.

The awesome day for Scriabin, imprisoned here on earth, was a celebration.

With death ends the tragic controversy

His soul of godlike colors, his majestic power, heroic doubts…

Scriabin is dead.

It is well for him but awesome for us who were lured by his genius.

The prisoner grew weary.

And still, we are left with the riddle of life.

Alexander Scriabin: 2 Poems, Op. 32 (Xiayin Wang, piano)

The novelist Boris Pasternak called the beginning of the 20th century the “era of Scriabin,” and he was seen as the major modernist composer of Russia. Scriabin was regarded as an almost mythical figure. The critic Asafiev wrote, “The proud idea of Scriabin as man-god places the human soul in the center of the universe like the sun. He did not turn towards the sun like sun-worshiping Orientals. He wanted to be absorbed into it, to become it, to fuse with the Sun itself… He has yet to become a legend, for people finally will believe only in legends.”

Scriabin’s funeral

Scriabin’s philosophy and music had little influence on younger Russian composers, but the “early Soviet era considered him a composer who most convincingly represented the revolutionary character of the era and thus appealed not only to musicians but also to the fledgling authorities and the newly widened concert-going public.” And Anatoly Lunacharsky, Commissar for Public Enlightenment, wrote in 1930, “Scriabin well understood the instability of the society in which he lived … he felt the electricity in the air and reacted to its disturbance. In his music, we have the great gift of the Revolution’s musical Romanticism.”

Alexander Scriabin: Preludes, Op. 11

Scriabin’s reputation in Russia began to decline after World War I, and he was criticized for his “acute and morbid neuropathic egocentricity, for being totally un-Russian in his themes, and more anti-people than anything in the whole of Russian music.” The composer Aaron Copland called Scriabin’s music “one of the most extraordinary mistakes of all times,” and he was also described as a composer “who possessed remarkable talent as a craftsman but who allowed his sense to be stifled by foolishly pursuing a narrow course in music that led him into an artistic cul-de-sac. Scriabin was a musical epigrammist with boundless egotism; in his youth, he showed great promise, but although his accomplishments are by no means inconsiderable, it became perfectly obvious towards the end of his rather short life that he had written himself out and was disguising his lack of inspiration by the use of cunning structural eccentricities.”

Scriabin’s funeral

Scriabin’s reputation has recently undergone a fundamental change of direction, and the theorist Anton Kuerti writes, “Sprays of esoteric arpeggios, puffs of musical smoke, tantalisingly eccentric rhythms, shivering, obsessive trills, jack-hammered chord accompaniments, cavalcades of flying chords, all imbued with his very personal, nearly toxic harmonic colours—these changed the face of piano writing forever.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Alexander Scriabin: Le Poème de l’extase, Op.54

The critics come and go. The music endures if it touches the human spirit.