Pianist Hans von Bülow was called upon on 25 October 1875 to play the first performance of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 at the Music Hall in Boston. Tchaikovsky wrote to Bülow, “Thank you for the sympathetic attention you have shown towards my composition. What an extraordinary country America is! Everything is grandiose and assumes gigantic proportions that nothing in Europe can approach.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1875

“When I think that you have given six concerts in a comparatively small town like Boston, when I recall all the bravos and calls that compelled you to repeat the concerto’s finale, when I marvel at the respectable sum that Chickering had to pay your secretary for the honour of furnishing you with his instruments, I am seized with astonishment and admiration!”

However, von Bülow had not been Tchaikovsky’s first choice. On Christmas Eve of 1874, Tchaikovsky presented the complete score of the concerto to Nikolai Rubinstein, hoping that the famed pianist would take on the task of presenting the work to the public. Rubinstein had been one of the composer’s strongest supporters, but things did not go according to plan.

As Tchaikovsky writes to Nadezhda von Meck. “I played the first movement. Never a word, never a single remark. Do you know the awkward and ridiculous sensation of putting before a friend a meal which you have cooked yourself, which he eats – and then holds his tongue? Oh, for a single word, for friendly abuse, for anything to break the silence! For God’s sake say something! But Rubinstein never opened his lips.”

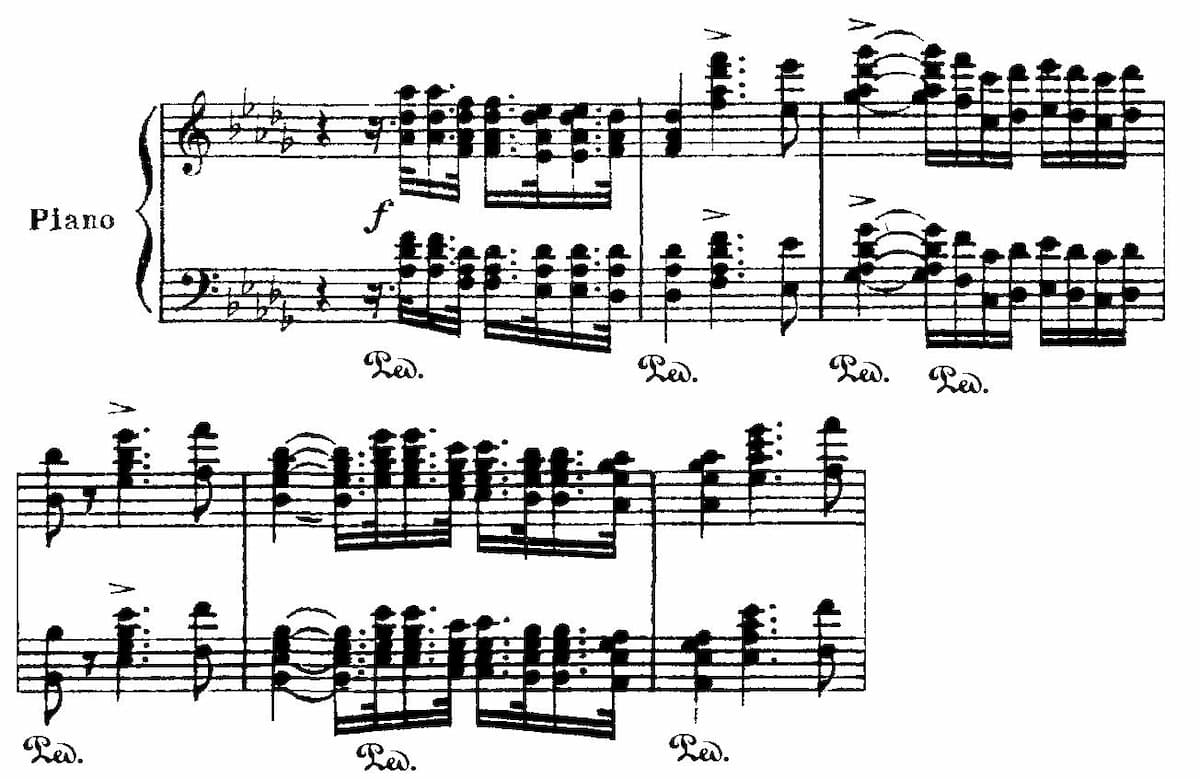

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23 “Allegro non troppo”

Tchaikovsky played through the entire concerto, and still, Rubinstein did not say a word. As Tchaikovsky reports, “‘Well?’ I asked and rose from the piano. Then a torrent broke from Rubinstein’s lips, gentle at first, gathering volume as it proceeded, and finally bursting into the fury of a Jupiter.

My Concerto was worthless, absolutely unplayable; the passages so broken, so disconnected, so unskilfully written, that they could not even be improved; the work itself was bad, trivial, common; here and there I had stolen from other people; only one or two pages were worth anything; all the rest had better be destroyed. I left the room without a word. Presently Rubinstein came to me and, seeing how upset I was, repeated that my Concerto was impossible but said if I would suit it to his requirements he would bring it out at his concert. I shall not alter a single note, I replied.”

Nikolai Rubinstein

Tchaikovsky was deeply insulted and during January 1875 he fully orchestrated the work and put the finishing touches on the composition in February. Since he wasn’t on speaking terms with Rubinstein, it was time to find another pianist. His choice fell on Hans von Bülow who responded enthusiastically. “Perhaps it would be presumptuous on my part,” wrote Bülow, “being unfamiliar with the whole scope of your works and prodigious talent, to say that for me your Op. 23 displays such brilliance, and is such a remarkable achievement among your musical works, that you have without doubt enriched the world of music as never before.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23 “Andantino Semplice”

Bülow heard a work of “unsurpassed originality, nobility, strength, and many arresting movements throughout this unique conception; there is such a maturity of form, such style—its design and execution, with such consonant harmonies, that I could weary you by listing all the memorable moments which caused me to thank the author—not to mention the pleasure from performing it all. In a word, this true gem shall earn you the gratitude of all pianists.”

Hans von Bülow

Possibly, Tchaikovsky still had Rubinstein’s assessment in mind when he decided to make some changes after the first few performances. Bülow wasn’t happy and wrote, “Why did you write that you want to make changes to your concerto? Naturally, I received them with great interest—but at this point, I should tell you frankly that in my view no changes are necessary—except for some augmentations to the piano part in a few tutti, which I had already introduced myself.”

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

One year after the full score was published in 1879 by Jurgenson, Tchaikovsky was still looking to issue a revised version with the publisher Rahter. He consulted with Aleksandr Ziloti about possible changes, asking for a review of the “cursed passage” in the finale. “I think it will be shorter and better; mainly because where previously there had been the strange rhythmic motif… this aberration has now been eliminated.” In the end, Rahter advertised a “new edition, revised by the composer,” in 1889, and Jurgenson issued his 3rd revised edition, the version we are familiar with today, shortly thereafter.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter