The music of Alfred Schnittke is marked by an intense expressiveness, an unpredictable flow of ideas, an innate sense of drama, and a natural lyricism. While traditional genres retained their relevance, Schnittke gave new life to old forms by squeezing radically different compositional styles into the same composition. His polystylistic approach and construction keep the music in constant dialogue with the past, and it generates extraordinary dramatic power with great audience appeal.

Alfred Schnittke: Cello Sonata No. 1, Op. 129

Ancestry

Alfred Schnittke

Schnittke was born on 24 November 1934 in Engels in the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. His grandmother Tea Abramovna Katz and his grandfather Viktor Mironovich Schnittke, originated from Libava, initially part of the Russian Empire, then independent Latvia, and later part of the Soviet Union. Both started their careers as revolutionary Communists, and by 1910, they fled to Germany in order to avoid trouble.

His grandmother was a philologist, translator, and editor of German-language literature, and by 1927, his grandparents had returned to Russia. Their son, Harry Maximilian Schnittke was born in Frankfurt but eventually established a career in Engels. Alfred’s mother, Maria Iosifovna Schnittke (née Vogel) came from a peasant family of Volga Germans, and in the early 1930s, the family looked for job opportunities in Engels.

Alfred Schnittke: Music for Piano and Chamber Orchestra (Vassily Lobanov, piano; Russian State Symphony Orchestra; Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond.)

Vienna

Alfred Schnittke’s family

Harry and Maria met and married in Engels, with his father working for a German newspaper and for German Radio. Young Alfred showed some musical ability from early on. Apparently, he was able to imitate different rhythms with a wooden spoon at the age of two, and he was glued to the radio. His parents quickly decided that Alfred should study music, and by age 7, he was sent to Moscow to audition for the Central Music School for gifted children. However, as German troops invaded Russia only a couple of weeks later, Alfred was sent back home to Engels.

The family survived the hardship of the war years, and in 1945, Harry Schnittke took up a position in Vienna, working for a local news department of a Soviet newspaper. The family finds themselves in a totally different world, and Alfred falls in love with music. “I felt every moment there,” he wrote, “to be a link of the historical chain; all was multi-dimensional; the past represented a world of ever-present ghosts, and I was not a barbarian without any connections, but the conscious bearer of the task in my life.”

Alfred Schnittke: Fugue for Solo Violin

Essentially Classical

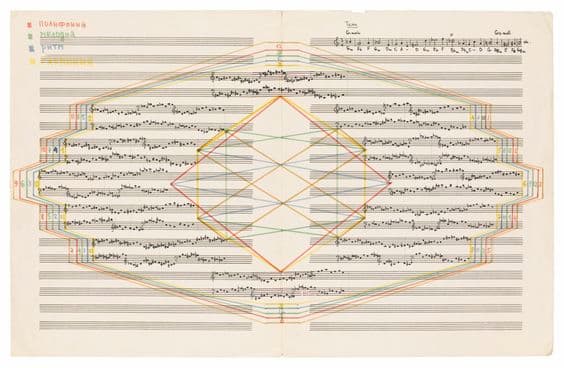

Alfred Schnittke’s graphic score of Cantus Perpetuus

Although the War had destroyed much of Vienna, music performances continued everywhere. Young Alfred was immediately drawn to the opera, and he saw Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci and Mascagni’s Cavalleria, as well as Mozart’s Entführung and Wagner’s Walküre. Apparently, he was much impressed by Otto Klemperer conducting Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony. He disliked the music of Debussy, and found Stravinsky overly complicated.

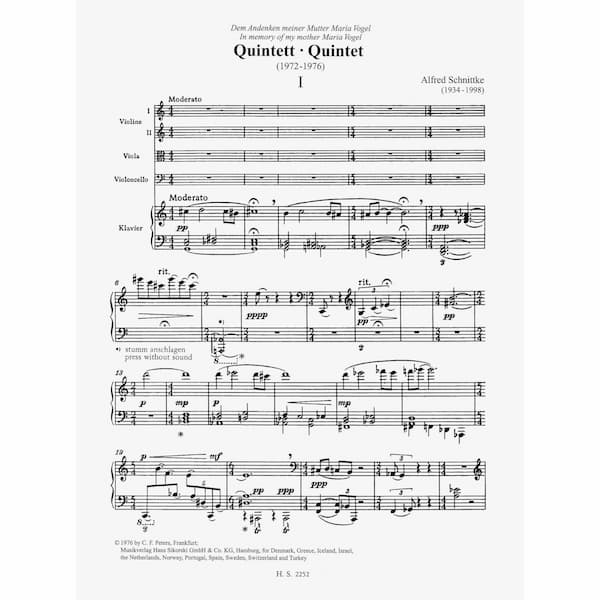

During his two years in Vienna, Alfred fundamentally established his basic criteria and future tastes in music. Mozart and Schubert became an essential part of his native musical tongue, and as Alexander Ivashkin writes, “in his symphonies, his Quintet and his Trio, all the lyrical highlights and all the positive musical symbols are indubitably Viennese.” His musical reference point was essentially Classical, “but never too blatant.”

Alfred Schnittke: Piano Quintet (Capricorn Ensemble; Timothy Mason, cond.)

Back to the USSR

Alfred Schnittke’s Piano Quintet

In 1948, the newspaper Harry Schnittke was working for closed down, and the family relocated to Moscow. Alfred was keen to study music, but he soon realised that it was too late to start a professional career as a performer. He did consult with a number of teachers at the famous Gnesin Institute, and it was decided that he should start learning the double bass. Fortunately, a friend of his father was a singer in the Red Army Choir, who referred Alfred to the “October Revolution Music College,” where he studied choral conducting.

Schnittke realised that he did not have adequate knowledge of harmony, theory, and analysis. As such, he started taking lessons with Iosif Ryzhkin, a well-known theorist who had published several books on the subject. Schnittke started regular private lessons with Ryzhkin in 1950, studying harmony in his first year, musical forms in his second, and composition in his third. Under Ryzhkin’s supervision, Schnittke composed a number of short pieces in different styles, and he also wrote his first piano concerto. On the strength of that score, it was decided that he should apply for study at the Moscow Conservatory.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter