During the final decade of his life, Jean Sibelius achieved great popularity in English-speaking countries while central Europe and France remained essentially uninterested.

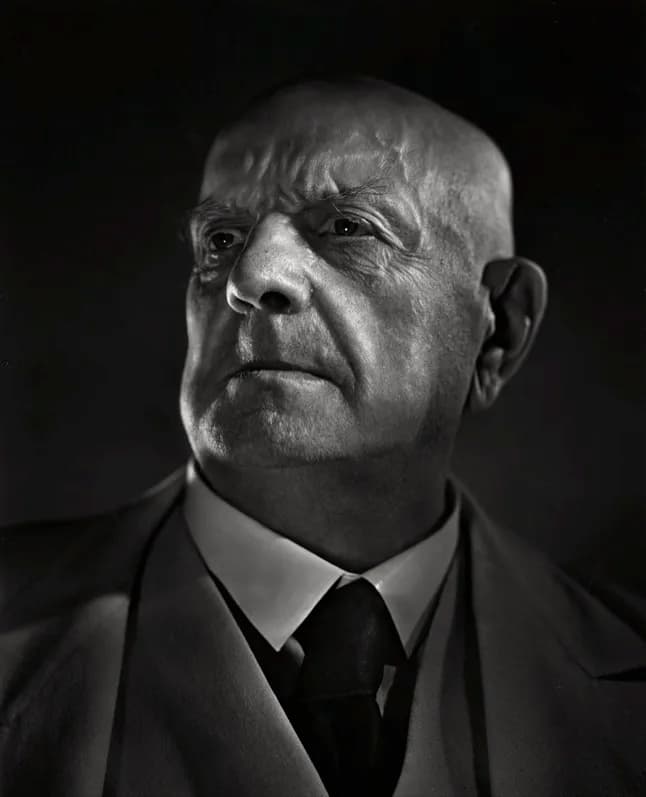

Jean Sibelius

Sibelius’ music polarized along ideological lines, and his supporters considered him the “last true successor to Beethoven and a fortress against the dissonant new music.” Pro-modernist factions, on the other hand, described the music as expressing “a shabbily deluded, market-driving false consciousness” and denounced the composer’s musical technique as the “originality of helplessness.” In fact, Sibelius was called “the worst composer in the world.”

Jean Sibelius: The Wood-Nymph

Major Compositions from 1920s to 1957

Jean and Aino Sibelius in front of Ainola in 1925

Sibelius composed prolifically until the mid-1920s, but after completing his Seventh Symphony (1924), the incidental music for The Tempest (1926), and the tone poem Tapiola (1926), he stopped producing major works in his last 30 years. This so-called “Silence from Järvenpää,” making reference to the location of his home, did produce less music than before, but Sibelius certainly did not stop composing.

He continued work on an Eighth Symphony, wrote Masonic ritual music, and re-edited some earlier works. By the late spring of 1957, Sibelius made new orchestral arrangements of two songs for the bass-baritone Kim Borg, but he could no longer write down the notes and had to dictate the orchestration to Jussi Jalas. During the summer months, Sibelius became increasingly introverted, and he seldom left the house.

Jean Sibelius: 3 Sketches from Sibelius’ “Lost” 8th Symphony

The Last Months of Sibelius

The Sibelius family

The Finnish writer Santeri Levas recalled, “During the last months the master’s home seemed strangely altered… The life force of its owner no longer irradiates the place. He was in retreat from life, and he knew well that his last hour would soon strike.” Sibelius went on his customary morning walk on an overcast morning on 18 September, when he saw a flock of cranes flying over Ainola. Sibelius had not seen cranes for many years, and he excitedly told his daughter Margareta.

“There they come, the birds of my youth,” he exclaimed. As he reported, suddenly, one of the birds broke away from the formation and circled once above Ainola. It then re-joined the flock to continue the migration southwards. The next day Sibelius discussed his Third Symphony on the telephone with the conductor Matti Similä. He also talked with Sir Malcolm Sargent, who had just arrived in Helsinki to conduct a broadcast performance of the Fifth Symphony with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra the following evening.

Jean Sibelius: The Swan of Tuonela

Cause of Death

Grave of Jean and Aino Sibelius

When Sibelius woke up on 20 September, he felt dizzy but was still able to read the newspaper in bed. He did get up and dressed himself, but the composer collapsed at the lunch table. His physician arrived within 15 minutes and diagnosed a cerebral haemorrhage, and Sibelius was escorted back to bed. He did manage to speak a couple of words but passed away around nine in the evening.

As Sibelius was barely hanging on to life, the performance of the Fifth Symphony was already underway. Aino turned on the radio, and according to their daughter Katarina, “Mother had the illusion that, if the radio volume were turned up loud, perhaps he would wake up again. This was wishful thinking. Father was beyond reach.”

Jean Sibelius: Masonic Ritual Music, Op. 113, “Funeral March” (Harri Viitanen, organ)

The Funeral Service

The funeral cortege of Sibelius

Newspapers reported Sibelius’ passing with major articles, and the coffin was driven to Helsinki. As Sibelius made his final journey, more and more cars joined in, and in the end, the cortege was over a mile long. Helsinki prepared for a state funeral, and on 30th September the funeral service took place at Helsinki Cathedral. Music included several of Sibelius’ hymn settings, as well as several movements from The Tempest, The Swan of Tuonela, the slow movement of the Fourth Symphony, and the funeral march In memoriam.

Funeral of Sibelius, 1957

After the ceremony, which ended with the strains of the funeral march from the Masonic Ritual Music, the procession made its way back to Ainola, where the coffin was carried by members of his family to a secluded corner of the garden. When winter arrived, Aino wrote to her brother, “Now I am alone here, nature in its white beauty is glistening outside. Every day I devoutly visit the grave of my own life companion. You probably know that the grave is very close by, and I can switch on the light from indoors to illuminate the grave and say goodnight to Janne from the window of my own room. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to cope.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter