Anton Rubinstein, Russian pianist, composer, conductor and teacher, was one of the greatest pianists of the 19th century. His playing was compared with Liszt’s, and he combined a prodigious technique with musicianship, scholarship, and a richly poetic temperament. Anton Rubinstein was highly influential in Russian musical circles as he founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, and taught among many others, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Rubinstein was also a prolific composer, who has five piano concertos, six symphonies, solo piano works and a substantial number of chamber music to his name.

Anton Rubinstein: Melody in F, Op. 3, No. 1

Controversy

Portrait of Composer Anton Rubinstein by Michail Michailovich Yarowoy

Throughout much of his life and career, Anton Rubinstein was at odds with a number of cultural and musical currents of his time. He steadfastly maintained that “music could not be a vehicle for a national style,” and he abhorred musical amateurism. He was well aware of his contentious reputation as he wrote, “Russians call me German, Germans call me Russian, Jews call me a Christian, Christians a Jew. Pianists call me a composer, composers call me a pianist. The classicists think me a futurist, and the futurists call me a reactionary. My conclusion is that I am neither fish nor fowl—a pitiful individual.”

Toward the end of his life his health, and particularly his mental constitution, increasingly deteriorated. He was seen to fall into depressions, especially in conjunction with the deaths of close members of his family. Rubinstein spent the last six months of his life in the relative calm of his Russian residence of Peterhof, “living here quietly and pleasantly.”

Anton Rubinstein: Cello Sonata No. 2 in G Major, Op. 39 (Gert von Bülow, cello; Jose Ribera, piano)

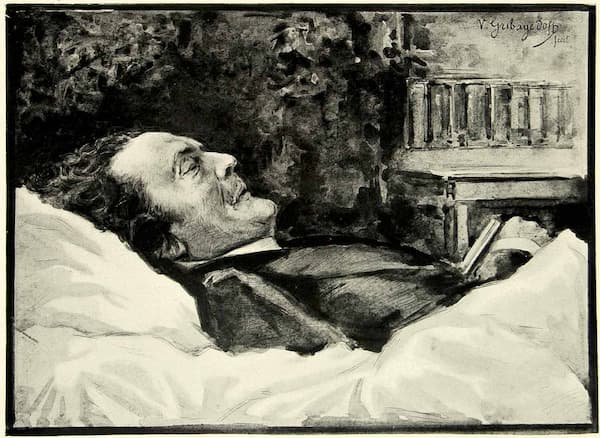

Death

Anton Rubinstein silhouette

Rubinstein, apparently, had been suffering from a heart condition that he refused to have surgically treated. As such, he died on 20 November 1894 just shy of his 65th birthday, and the Times wrote “As a man he was of most lovable character, of superb generosity and unselfishness. Through his whole career he was eager to assist various charitable objects by the proceeds of his concerts, and in his farewell series not only were the concerts repeated for the instruction of musical students, but the whole profits were devoted to charity.”

The funeral rites continued for the entire week after his death and Philip S. Taylor writes, “The composer’s body lay in an open coffin. Two rows of soldiers lined the route from the railing surrounding the catafalque to the church pulpit, and the western entrance to Trinity Church in St. Petersburg, was packed with police. The music critic Nikolay Findeysen was horrified by the spectacle of orders being shouted to the men inside the church as if they were on a parade ground.”

Anton Rubinstein: Persian Songs, Op. 34 (Hamish McLaren, counter-tenor; Matthew Jorysz, piano)

Commemoration

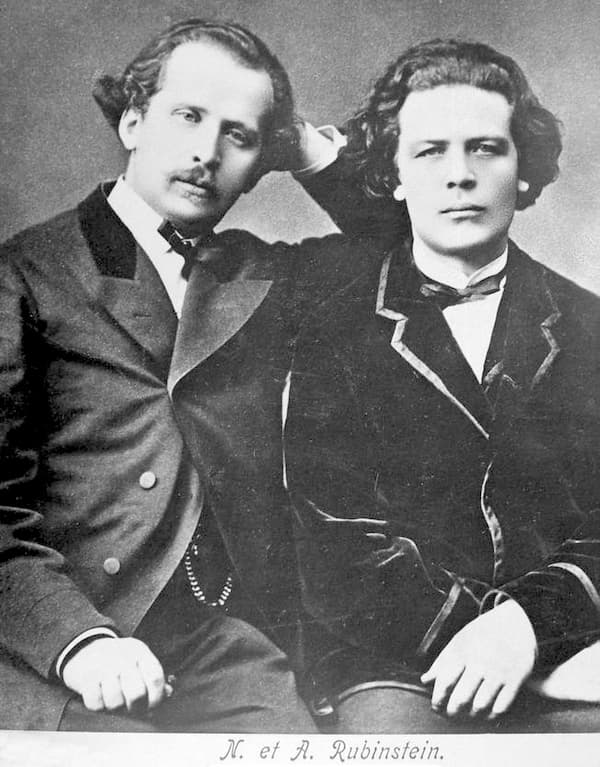

Nikolai and Anton Rubinstein

The general public had not been admitted, and “outside there was swearing, showing, arguing, police, and crowding. And in the church, the deceased, a great man and soldiers in uniforms and troops ready for the attack.” As Taylor contents, “this extraordinary episode makes clear that even in death Rubinstein could never avoid bitter controversy.” Rubinstein was eventually interred at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg near the graves of Dargomiszhky and Tchaikovsky.

On 24 December 1896, the opening of the new St. Petersburg Conservatory building was celebrated with a concert featuring, among others, Rubinstein’s Triumphal Overture, a work he had completed shortly before his death. That overture was heard again in a concert on 19 April 1901 to celebrate the opening of the new Moscow Conservatory. Vasily Safonov conducted and he paid tribute to Rubinstein by calling him one of the three great Russian symphonists alongside Borodin and Tchaikovsky.

Anton Rubinstein: Symphony No. 2 in C Major, Op. 42 “Ocean” (Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra; Stephen Gunzenhauser, cond.)

Legacy

Anton Rubinstein lying in state

Rimsky-Korsakov was never a fan of Rubinstein’s music and he writes, “I’m coming to the sad conclusion that his symphonic music can be characterised as follows; If, while listening to something you don’t know, you have the feeling that it’s either bad Beethoven or poorly orchestrated Mendelssohn, and if, at the same time, it never strikes you as downright tasteless or ugly, but, on the other hand, there’s nothing daring about it—on the contrary everything about it seems proper and descent, even if hopelessly monotonous—then you can be sure you’re listening to one of Rubinstein’s many works of his kind.”

Anton Rubinstein had been a pianistic legend, but his reputation survived only as long as people who had been fortunate enough to hear him play could remember. Taylor writes, “With one or two exceptions, his compositions were virtually forgotten as repertory pieces within twenty-five years of his death.” Rubinstein was aware that his works would barely outlive him, yet he held up hope that “sometimes, excavations will yield it up when the right time comes.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter